Dr. Robert Lyman discusses the state of the British Army through the Cold War years down to today, with emphasis on the defence budget tracking against perceived threats to the UK and allies over that period:

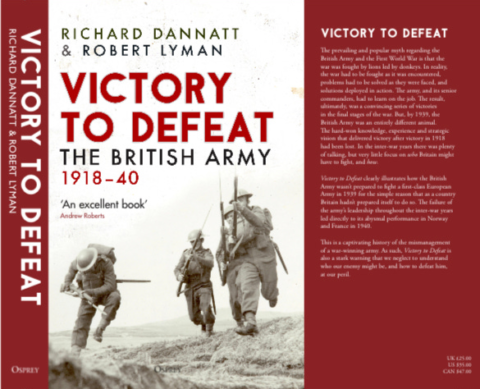

Last year General Lord Dannatt and I published an account of the British Army between 1918 — when it achieved a great victory — and 1940, when it did not. The book was written in part to challenge the UK to think seriously about what happens when our country neglects the requirement for an army able to fight at a high-intensity for a prolonged period against a peer adversary.

Part of our argument was to look at the amount of money the country spends on its defence as a barometer of the seriousness or otherwise of our political masters towards spending money on the primary duty of government, namely the security of its citizens. Our fear is that in the rampant feel-goodery that has plagued the West since 1991 the harsh realities of our unstable world have become forgotten. It has taken Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, and Russia’s subsequent bludgeoning of that benighted country for politicians to gradually wake up to the scale of the threat that this sort of instability offers to the world, not merely Europe or the West.

My fear, like that of many others, is that the wake-up call is taking too long and our country’s defences remain in a parlous state. We haven’t had an army able to deploy at divisional level or above in sustained all-arms manoeuvre for perhaps ten years or more. In other words, our ability to provide what our forefathers would have described as a robust “continental commitment” is almost non-existent.

In the book we trace the origins of the failure to think seriously about the need to have a deployable, expeditionary army, able to fight and operate alongside its allies in NATO on an all-arms battlefield. The reality is that the Cold War forced Britain to retain the ability to fight a general war in Europe, all the while finding the resources to undertake its other commitments across the world. Although worldwide events were dynamic from 1945 to 1989 with further conflicts for the United Kingdom in Malaya, Dhofar, Cyprus, Kenya, Borneo, the Falklands, and the long-running Troubles in Northern Ireland, it was the Cold War in Europe that principally drove the defence agenda and kept the budget at around 5 per cent of GDP. As the major bridge between the United States and Europe, the Royal Navy was heavily committed above and below the surface of the Atlantic Ocean to keep open the sea lines of communication to NATO’s dominant partner, while the British Army retained some 55,000 troops in four armoured divisions as part of NATO’s Northern Army Group and the Royal Air Force was also largely forward-based in West Germany as part of the Second Allied Tactical Air Force. These conventional deployments were all conducted under the nuclear umbrella of Mutual Assured Destruction. By the 1980s, with the West under the leadership of US President Ronald Reagan and British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and with increased spending on both conventional armaments and the highly experimental Inter-Continental Ballistic Missile Defence system, the strain of strategic military competition began to show on the political and economic stability of the Soviet Union. Despite the perestroika political movement for reform within the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and the associated openness of glasnost under General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev, the cracks in the Berlin Wall that opened on 9 November 1989 led inexorably to the collapse of the Soviet Union two years later and the old flag of Russia being raised over the Kremlin on 26 December 1991. The Cold War was over, and an apparent New World Order had begun. The historian Francis Fukuyama declared – somewhat ambitiously – the end of history.

It was at this point that international leaders and their finance ministers in the West began to overlook the cautionary tale that the history of the 20th century might have taught them. With the Soviet Union gone and rump Russia apparently enfeebled, Western states eagerly embarked on military reduction and a peace dividend. In the United Kingdom, the “Options for Change” exercise saw a major slashing of defence capability, beneficially coincidental to help ameliorate a significant economic downturn. The British Army was reduced from 155,000 to 116,000 soldiers, notwithstanding the first Gulf War of 1990–91 which many wishful thinkers regarded as something of an aberration. However, despite that war and the subsequent deployment of large parts of the armed forces to Bosnia from 1992 and then to Kosovo in 1999, the new Labour government of Prime Minister Tony Blair continued with the implementation of its Strategic Defence Review of 1997–98. As a piece of policy work, this was considered an honest review of the United Kingdom’s defence policy and a progressive blueprint for future defence planning and expenditure. Endorsed by Tony Blair and the Chiefs of Staff, this review might have stood the nation in good stead for the future had the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Gordon Brown, fully funded its outcome. For his own reasons, he chose not to do so. The underfunding of the United Kingdom’s defence capability began to show its deficiencies a year after with the second Gulf War of 2003, and the situation was then exacerbated by a protracted campaign in Iraq for the British Army lasting until 2009 and an even more intense one in Afghanistan lasting until 2014.