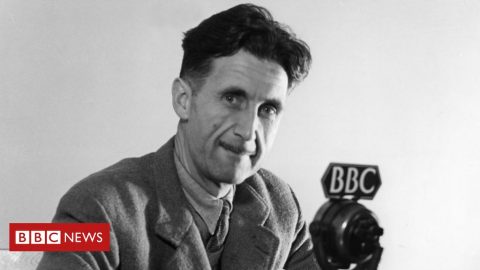

Jonathon Van Maren contacted Richard Horatio Blair, the adopted son of George Orwell to discuss his memories of his famous father:

“My story starts on the 14th of May, 1944, when I was adopted by Eric Arthur Blair and his wife Eileen,” he told me. “This was during the Second World War. He’d been wanting a child for several years because he felt, rightly or wrongly, that he was unable to have children himself. I think this was compounded slightly by the fact that Eileen — my mother — was not very well herself, and in fact when I was ten months old, in March of 1945, she went to the hospital in Newcastle, which was the area where she was born and had gone to school. She went into a nursing home and died very soon after being anesthetized to have a hysterectomy. She probably had cancer, was very anemic, and simply had a heart attack on the operating table and died.”

The adoption had come about when Eileen was told by her sister-in-law, Dr. Gwen Shaughnessy, that she knew of a pregnant woman whose husband was off fighting. Orwell and Eileen adopted Richard when he was only three weeks old, and Orwell ensured that he alone would be known as Richard’s father by burning the names of the birth parents from the birth certificate with a cigarette. Richard would never know Eileen, as she died a mere nine months after the adoption took place, leaving the little boy and Orwell to fend for themselves. Some of Orwell’s friends suggested that perhaps he turn Richard over to someone else, but Orwell was having none of it. “I’ve got my son now, I’m not going to give him over,” Blair recalled. Blair even remembers Orwell “changing my nappy and feeding me after my mother died.”

“Meanwhile, my father had been asked to go to Germany at the end of the war by his friend, a gentleman by the name of David Astor of the Astor family,” Blair told me.

He was the proprietor of a newspaper called The Observer, and he asked my father — they had met during the war and become friends — to go to Germany after the war to observe what was happening, and it was while he was in Paris that he got a telegram telling him that Eileen, my mother, had died. He had to rush back and attend to the funeral and funeral arrangements. He decided the best thing he could do would be to go back to Germany and continue his war report, so that’s what he did. I was placed in the hands of relatives and friends to be looked after. I was cared for from that period onward by a nanny.

In 1946, he had decided to give up his reviews and extra work, because by now he had published his first major book, Animal Farm, which gave him enough resources to think about what to do next. And he had in his mind by then that he wanted to write what turned out to be 1984, and he decided to take the invitation of his friend David Astor to go to a remote island off the west coast of Scotland called Jura. He went up for a holiday and spent a couple of weeks there in the early part of 1946, came back, and announced that he would like to move out of London to this island of Jura and rent a farmhouse called Barnhill. A few weeks later I joined him with my nanny at the farmhouse, a place he had indicated to a friend was a very ‘un-get-at-able’ place.

Indeed it was. To reach the remote Hebridean island from London, “you had to take a train and several ferries, and then a taxi from the top part of the island, and then for the last five miles you had to walk,” Blair recalled. At first, it was Richard, Orwell, and his nanny, Susie Watson. This didn’t last long: Watson clashed with Orwell’s younger sister Avril and returned to London. “From that point on,” Blair told me, “I was cared for by my father’s sister Avril, and that continued well past when he died in 1950.” In the meantime, Blair still had a few precious years with his ailing father, who was trying to balance his fear of passing on his tuberculosis to his son with wanting to be an involved father. “He was really hands-on in a way that was really unusual for that era,” Blair told one interviewer.

In fact, he was so hands-on that he even worried about Richard’s television consumption, which is perhaps not surprising from someone who was so concerned about how people absorbed information — but Richard was, at this point, a very small child. “As a father he was completely devoted to me,” Blair told me. “He was terribly worried about my emotional development simply because he had TV, and he was very concerned that the views [on TV] might be passed on to me.” Blair still bears a scar on his temple from balancing on a chair while “watching him make a wooden toy for me”. He fell off the chair, cracked his head, and was bustled down to the village for a few stitches in the enormous gash on his forehead. “There’s a groove in the bone,” he ruefully told one interviewer. But there were no tests in those days, and so his head was sewn shut and he was sent back home again.