Ed West visited East Berlin as a child and came away unimpressed with the grey, impoverished half of Berlin compared to “the gigantic toy shop that was West Berlin”. The East German state was controlled by the few survivors of the pre-WW2 Communist leaders who fled to the Soviet Union:

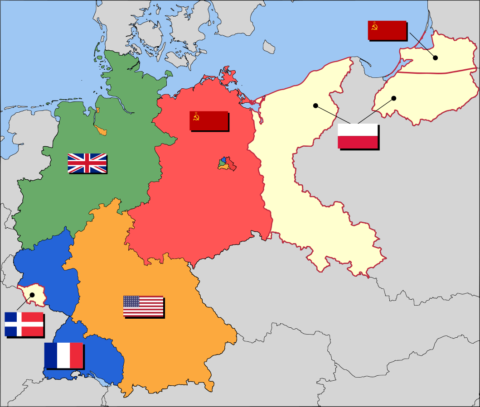

Occupation zone borders in Germany, 1947. The territories east of the Oder-Neisse line, under Polish and Soviet administration/annexation, are shown in cream as is the likewise detached Saar protectorate. Berlin is the multinational area within the Soviet zone.

Image based on map data of the IEG-Maps project (Andreas Kunz, B. Johnen and Joachim Robert Moeschl: University of Mainz) – www.ieg-maps.uni-mainz.de, via Wikimedia Commons.

In my childish mind there was perhaps a sense that East Germany, the evil side, was in some way the spiritual successor both to Prussia and the Third Reich – authoritarian, militaristic and hostile. Even the film Top Secret, one of the many Zucker, Abrahams and Zucker comedies we used to enjoy as children, deliberately confused the two, the American rock star stuck in communist East Germany then getting caught up with the French resistance. The film showed a land of Olympic female shot put winners with six o’clock shadows, crappy little cars you had to wait a decade for, and a terrifying wall to keep the prisoners in – and compared to the gigantic toy shop that was West Berlin, I was not sold.

I suppose that’s how the country is largely remembered in the British imagination, a land of border fences and spying, The Lives of Others and Goodbye Lenin. When the British aren’t comparing everything to Nazi Germany, they occasionally stray out into other historic analogies by comparing things to East Germany, not surprising in a surveillance state such as ours (these rather dubious comparisons obviously intensified under lockdown).

This is no doubt grating to East Germans themselves, but perhaps more grating is the sense of disdain often felt in the western half of Germany; for East Germans, their country simply ceased to exist in 1990 as it was gobbled up by its larger, richer, more glamorous neighbour, and has been regarded as a failure ever since. For that reason, [Katja] Hoyer’s book [Beyond the Wall] is both enjoyable holiday reading and an important historical record for an ageing cohort of people who lived under the old system. To have one’s story told, in a sense, is to avoid annihilation.

Despite the similarities between the two totalitarian systems, East Germany almost defined itself as the anti-fascist state, and its origins lie in a group of communist exiles who fled from Hitler to seek safety in the Soviet Union. Inevitably, their story was almost comically bleak; 17 senior German Marxists in Russia ended up being executed by Stalin, suspected by the paranoid dictator of secretly working for Germany. Even some Jewish communists were accused of spying for the Nazis — which seems to a rational observer unlikely. As Hoyer writes, “More members of the KPD’s executive committee died at Stalin’s hands than at Hitler’s”.

Only two of the nine-strong German politburo survived life in Russia, one of these being Walter Ulbricht, the goatee-bearded veteran of the failed 1919 German revolution and communist party chairman in Berlin in the years before the Nazis came to power.

The war had brutalised the eastern part of Germany far more than the West. It suffered the revenge of the Red Army, including the then largest mass rape in history, and the forced expulsion of millions of Germans from further east (including Hoyer’s grandfather, who had walked from East Prussia). The country was utterly shattered.

From the start the Soviet section had huge disadvantages, not just in terms of raw materials or industry – western Germany has historically always been richer — but in having a patron in Russia. While the Americans boosted their allies through the Marshall Plan, the Soviets continued to plunder Germany; when they learned of uranium in Thuringia they simply turned up and took it, using locals as forced labour.

“In total, 60 per cent of ongoing East German production was taken out of the young state’s efforts to get on its feet between 1945 and 1953,” Hoyer writes: “Yet its people battled on. As early as 1950, the production levels of 1938 had been reached again despite the fact that the GDR had paid three times as much in reparations as its Western counterpart.”

After the war, so-called “Antifa Committees” formed across the Soviet zone, “made up of a wild mix of individuals, among them socialists, communists, liberals, Christians and other opponents of Nazism”. Inevitably, a broad and eclectic left front was taken over by communists who soon crushed all opposition.

And as with many regimes, state oppression grew worse over time. “By May 1953, 66,000 people languished in East German prisons, twice as many as the year before, and a huge figure compared to West Germany’s 40,000. The General Secretary’s revival of the ‘class struggle’, officially announced in the summer of 1952 as part of the state’s ‘building socialism’ programme, had escalated into a struggle against the population, including the working classes.” The party was also becoming dominated by an educated elite, as happened in pretty much all revolutionary regimes.

Protests began at the Stalinallee in Berlin on 16 June 1953, where builders marched towards the House of Ministries and “stood there in their work boots, the dirt and sweat of their labour still on their faces; many held their tools in their hands or slung over their shoulders. There could not have been a more fitting snapshot of what had become of Ulbricht’s dictatorship of the proletariat. The angry crowd chanted, ‘Das hat alles keinen Zweck, der Spitzbart muss weg!’ – ‘No point in reform until Goatee is gone!'”

The 1953 protests were crushed, the workers smeared as fascists, but three years later came Khrushchev’s famous denunciation of Stalin, which caused huge trauma to communists everywhere. “The shaken German delegation went back to their rooms to ponder the implications of what they had just learned.” By breakfast time, “Ulbricht had pulled himself together”, and decreed the new party line. Stalin, it was announced “cannot be counted as a classic of Marxism”.