Bill Lyman outlines one of the significant factors assisting General Slim’s XIVth Army to recapture Burma from the Japanese during late 1944 and early 1945:

If Lieutenant General Sir Bill Slim (he had been knighted by General Archibald Wavell, the Viceroy, the previous October, at Imphal) had been asked in January 1945 to describe the situation in Burma at the onset of the next monsoon period in May, I do not believe that in his wildest imaginings he could have conceived that the whole of Burma would be about to fall into his hands. After all, his army wasn’t yet fully across the Chindwin. Nearly 800 miles of tough country with few roads lay before him, not least the entire Burma Area Army under a new commander, General Kimura. The Arakanese coastline needed to be captured too, to allow aircraft to use the vital airfields at Akyab as a stepping stone to Rangoon. Likewise, I’m not sure that he would have imagined that a primary reason for the success of his Army was the work of 12,000 native levies from the Karen Hills, under the leadership of SOE, whose guerrilla activities prevented the Japanese from reaching, reinforcing and defending the key town of Toungoo on the Sittang river. It was the loss of this town, more than any other, which handed Burma to Slim on a plate, and it was SOE and their native Karen guerrillas which made it all possible.

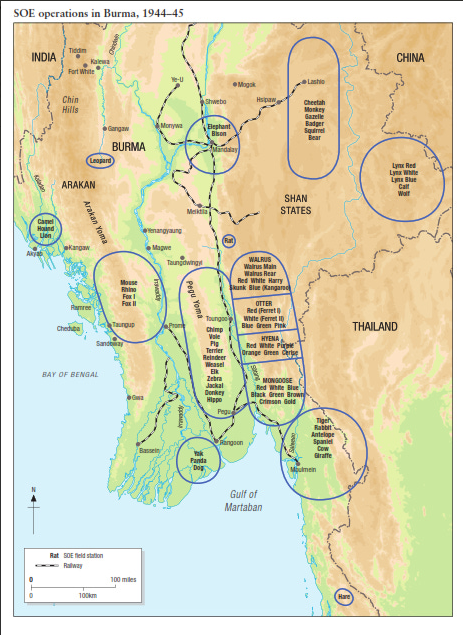

In January 1945 Slim was given operational responsibility for Force 136 (i.e. Special Operations Executive, or SOE). It had operated in front of 20 Indian Division along the Chindwin between 1943 and early 1944 and did sterling work reporting on Japanese activity facing 4 Corps. Persuaded that similar groups working among the Karens in Burma’s eastern hills – an area known as the Karenni States – could achieve significant support for a land offensive in Burma, Slim authorised an operation to the Karens. Its task was not merely to undertake intelligence missions watching the road and railways between Mandalay and Rangoon, but to determine whether they would fight. If the Karens were prepared to do so, SOE would be responsible for training and organising them as armed groups able to deliver battlefield intelligence directly in support of the advancing 14 Army. In fact, the resulting operation – Character – was so spectacularly successful that it far outweighed what had been achieved by Operation Thursday the previous year in terms of its impact on the course of military operations in pursuit of the strategy to defeat the Japanese in the whole of Burma. It has been strangely forgotten, or ignored, by most historians ever since, drowned out perhaps by the noise made by the drama and heroism of Thursday, the second Chindit expedition. Over the course of Slim’s advance in 1945 some 2,000 British, Indian and Burmese officers and soldiers, along with 1,430 tons of supplies, were dropped into Burma for the purposes of providing intelligence about the Japanese that would be useful for the fighting formations of 14 Army, as well as undertaking limited guerrilla operations. As Richard Duckett has observed, this found SOE operating not merely as intelligence gatherers in the traditional sense, but as Special Forces with a defined military mission as part of conventional operations linked directly to a military strategic outcome. For Operation Character specifically, about 110 British officers and NCOs and over 100 men of all Burmese ethnicities, dominated interestingly by Burmans mobilised as many as 12,000 Karens over an area of 7,000 square miles to the anti-Japanese cause. Some 3,000 weapons were dropped into the Karenni States. Operating in five distinct groups (“Walrus”, “Ferret”, “Otter”, “Mongoose” and “Hyena”) the Karen irregulars trained and led by Force 136, waited the moment when 14 Army instructed them to attack.

Between 30 March and 10 April 1945 14 Army drove hard for Rangoon after its victories at Mandalay and Meiktila, with Lt General Frank Messervy’s 4 Indian Corps in the van. Pyawbe saw the first battle of 14 Army’s drive to Rangoon, and it proved as decisive in 1945 as the Japanese attack on Prome had been in 1942. Otherwise strong Japanese defensive positions around the town with limited capability for counter attack meant that the Japanese were sitting targets for Allied tanks, artillery and airpower. Messervy’s plan was simple: to bypass the defended points that lay before Pyawbe, allowing them to be dealt with by subsequent attack from the air, and surround Pyawbe from all points of the compass by 17 Indian Division before squeezing it like a lemon with his tanks and artillery. With nowhere to go, and with no effective means to counter-attack, the Japanese were exterminated bunker by bunker by the Shermans of 255 Tank Brigade, now slick with the experience of battle gained at Meiktila. Infantry, armour and aircraft cleared General Honda’s primary blocking point before Toungoo with coordinated precision. This single battle, which killed over 1,000 Japanese, entirely removed Honda’s ability to prevent 4 Corps from exploiting the road to Toungoo. Messervy grasped the opportunity, leapfrogging 5 Indian Division (the vanguard of the advance comprising an armoured regiment and armoured reconnaissance group from 255 Tank Brigade) southwards, capturing Shwemyo on 16 April, Pyinmana on 19 April and Lewe on 21 April. Toungoo was the immediate target, attractive because it boasted three airfields, from where No 224 Group could provide air support to Operation Dracula, the planned amphibious attack against Rangoon. Messervy drove his armour on, reaching Toungoo, much to the surprise of the Japanese, the following day. After three days of fighting, supported by heavy attack from the air by B24 Liberators, the town and its airfields fell to Messervy. On the very day of its capture, 100 C47s and C46 Commando transports landed the air transportable elements of 17 Indian Division to join their armoured comrades. They now took the lead from 5 Indian Division, accompanied by 255 Tank Brigade, for whom rations in their supporting vehicles had had been substituted for petrol, pressing on via Pegu to Rangoon.