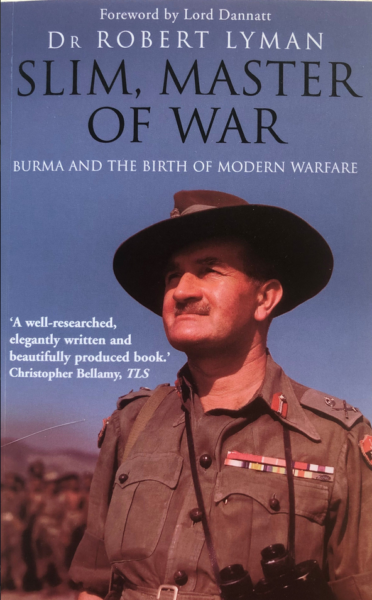

William Slim, arguably the best British general of the Second World War, didn’t have the fastest start to his military career, as recounted in an article by Frank Owen, the editor of the WW2 South East Asia theatre publication Phoenix. This and many others appear in Dr. Robert Lyman’s upcoming book Slim, Master of War:

The General stood on an ammunition box. Facing him in a green amphitheatre of the low hills that ring the Palel Plain, sat or squatted the British officers and sergeants of the 11th East African Division. They were then new to the Burma Front and were moving into the line the next day. The General removed his battered slouch hat, which the Gurkhas wear and which has become the headgear of the 14th Army. “Take a good look at my mug”, he advised. “Not that I consider it to be an oil painting. But I am the Army Commander and you had better be able to recognize me — if only to say “Look out, the old b…. is coming round”.

Lieutenant-General Sir William Slim, KCB, CB, DSO, MC (“Bill”) is 53, burly, grey and going a bit bald. His mug is large and weather beaten, with a broad nose, jutting jaw, and twinkling hazel eyes. He looks like a well-to-do West Country farmer, and could be one. For he has energy and patience and, above all, the man has common sense. However, so far Slim has not farmed. He started life as a junior clerk, once he was a school teacher, and then he became the foreman of a testing gang in a Midland engineering works. For the next 30 years Slim was a soldier.

He began at the bottom of the ladder as a Territorial private. August 4, 1914, found him at Summer camp with his regiment. The Territorials were at once embodied in the Regular Army, and Slim got his first stripe as lance-corporal. A few weeks later he was a private again, the only demotion that this Lieutenant-General has suffered.

It was a sweltering, dusty day and the regiment plodded on its twenty-mile route march down an endless Yorkshire lane. At that time British troops still marched in fours, so that Lance-Corporal Slim, as he swung along by the side of his men, made the fifth in the file, which brought him very close to the roadside. There were cottages there and an old lady stood at the garden gate.

“I can see her yet”, Slim reminisces. “she was a beautiful old lady with her hair neatly parted in the middle and wearing a black print dress. In her hand she held a beautiful jug, and on the top of that jug was a beautiful foam, indicating that it contained beer. She was offering it to the soldier boys.”

The Lance-Corporal took one pace to the side and grasped the jug. As he did, the column was halted with a roar. The Colonel, who rode a horse at its head, had glanced back. Slim was hailed before him and “busted” on the spot. The Colonel bellowed “Had we been in France you would have been shot.” Slim confides, “I thought he was a damned old fool – and he was. I lost my stripe, but he lost his army.” In truth he did, in France in March 1918. Bill soon got his stripe back.

Now in this corner of Palel Plain, one of India’s bloodiest battlefields and the scene of one of his greatest victories, Slim tells the officers and men of the 11th Division, “I have commanded every kind of formation from a section upwards to this army, which happens to be the largest single one in the world.” (At that time, Slim had under his command half a million troops.) “I tell you this simply that you shall realize I know what I am talking about. I understand the British soldier because I have been one, and I have learned about the Japanese soldier because I have been beaten by him. I have been kicked by this enemy in the place where it hurts, and all the way from Rangoon to India where I had to dust-off my pants. Now, gentlemen, we are kicking our Japanese neighbours back to Rangoon.”

Slim commanded the rear guard of the army that retreated from Burma in 1942. He is proud of that. His men marched and fought for a hundred days and nights and across a thousand miles. But this retreat was no Dunkirk. Says Slim “We brought our weapons out with us, and we carried our wounded, too. Dog-tired soldiers, hardly able to put one foot in front of another, would stagger along for hours carrying or holding up a wounded comrade. When at last they reached India over those terrible jungle mountains they did not go back to an island fortress and to their own people where they could rest and refit. The Army of Burma sank down on the frontier of India, dead beat and in rags. But, they fought here all through the downpour of the monsoon, and they saved India until a great new Army – which is this one – could be built up to take the offensive once again. In those days, if anyone had gone to me with a single piece of good news I would have burst out crying. Nobody ever did.”

He tells another story. One day he entered a jungle glade in a tank. In front of him stood a group of soldiers, in their midst the eternal Tommy. Assuming an optimism which he did not feel, Slim jumped out of the tank and approached them. “Gentlemen!” he said (which is the nice way that British generals sometimes address their troops) “Things might be worse!”

“‘Ow could they be worse?” inquired the Tommy.

“Well, it could rain” said Slim, lightly. He adds “And within quarter of an hour it did.”