In UnHerd, Dominic Sandbrook outlines the end of US involvement in the Vietnam War:

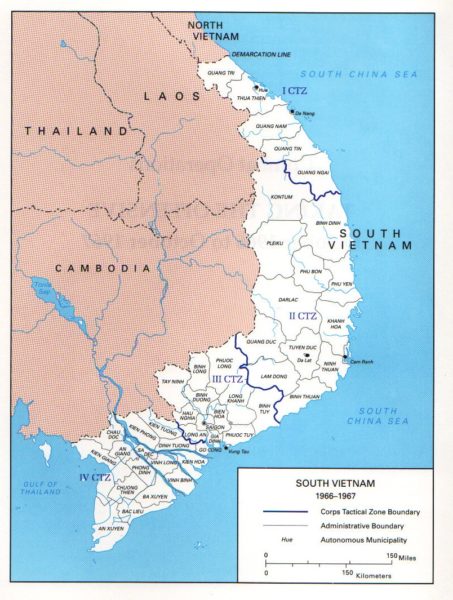

From George L. MacGarrigle, The United States Army in Vietnam: Combat Operations, Taking the Offensive, October 1966-October 1967. Washington DC: Center of Military History, 1998. (Via Wikimedia)

In the course of his troubled presidency, Richard Nixon spoke 14 times to the American people about the war in Vietnam. It was in one of those speeches that he coined the phrase “the silent majority”, while others provoked horror and outrage from those opposed to America’s longest war. But of all these televised addresses, none enjoyed a warmer reaction that the speech Nixon delivered on 23 January 1973, announcing that his Secretary of State, Henry Kissinger, had achieved a breakthrough in the Paris peace talks with the North Vietnamese.

At last, Nixon said, the war was over. At a cost of 58,000 American lives and some $140 billion, not to mention more than two million Vietnamese lives, the curtain was falling. The last US troops would be brought home. South Vietnam had won the right to determine its own future, while the Communist North had pledged to “build a peace of reconciliation”. Despite the high price, Nixon insisted Americans could be proud of “one of the most selfless enterprises in the history of nations”. He had not started the war, but it had dominated his presidency, earning him the undying enmity of those who thought the United States should just get out. But the struggle had been worth it to secure “the right kind of peace, so that those who died and those who suffered would not have died and suffered in vain”. He called it “peace with honour”.

Fifty years on, Nixon’s proclamation of peace with honour has a bitterly ironic ring. As we now know, much of what he said that night was misleading, disingenuous or simply untrue. South Vietnam was in no state to defend itself, and collapsed just two years later. The North Vietnamese had no intention of laying down their weapons, and resumed the offensive within weeks. And Nixon and Kissinger never seriously thought they had secured a lasting peace. They knew the Communists would carry on fighting, and fully intended to intervene with massive aerial power when they did. But then came Watergate. With Nixon crippled, Congress forbade further intervention and slashed funding to the government in Saigon. On 30 April 1975, North Vietnamese tanks crashed through the gates of the presidential palace, and it really was all over.

Half a century later, have the scars of Vietnam really healed? It remains not only America’s longest war but one of its most divisive, comparable only with the Civil War in its incendiary cultural and political impact. The fundamental narrative trajectory of the late Sixties — the turn from shiny space-age Technicolor optimism to strident, embittered, anti-technological gloom — would have been incomprehensible without the daily images of suffering and slaughter on the early evening news. It was Vietnam that destroyed trust in government, in institutions, in order and authority. In 1964, before Lyndon Johnson sent in combat troops after the Gulf of Tonkin incident, fully three-quarters of Americans trusted the federal government. By 1976, a year after the fall of Saigon, not even one in four did so.

It was in the crucible of Vietnam, too, that you can spot many of the tensions that now define American politics. Perhaps the most potent example came in May 1970, after Nixon invaded nominally neutral Cambodia to eliminate the North Vietnamese Army’s jungle sanctuaries. First, on 4 May, four students were shot and killed by the National Guard during a demonstration at Kent State University, Ohio. Then, on 8 May, hundreds more students picketed outside the New York Stock Exchange, only to be attacked by several hundred building workers waving American flags.

The “hard hat riot”, as it became known, was the perfect embodiment of patriotic populist outrage at what Nixon’s vice president, leading bribery enthusiast Spiro Agnew, called “the nattering nabobs of negativism … an effete corps of impudent snobs who characterise themselves as intellectuals”. Today it seems almost predictable, just another episode in the long-running culture wars. But at the time it seemed genuinely shocking. And with his brilliantly ruthless eye for a tactical advantage, Nixon saw its potential. When he invited the construction workers’ leaders to the White House two weeks later, he knew exactly what was doing. “The hard hat will stand as a symbol, along with our great flag,” he said, “for freedom and patriotism and our beloved country”.