Katherine Bayford on the awkward situation many western nations find themselves in, being both dependent to a greater or lesser degree on oil and gas imports from Russia and also having allowed their armed forces to degrade significantly over time:

After months of military build-up and overt threats, educated, intelligent and respected experts across the West woke on Thursday, 24 February — genuinely shocked to discover that Russia had launched an invasion of Ukraine.

How is it that people paid to conduct exactly this sort of analysis could be so badly wrong? The experts who apparently completely underestimated Russia’s intention to undertake major military action, ranged from analysts and academics to President Zelensky himself. Russia’s intentions were hardly a secret. To be shocked at this invasion — not that it occurred when it did, or that it was undertaken in the particular way it was, but to be shocked at the very realistic possibility that it could have occurred — was foolishly naïve. Many of these analysts, whose careers have been built upon understanding the actions of non-western states, suffer a profound inability to understand actors with different thought patterns and belief systems. At its core, their failure seems to arise from academics, journalists and diplomats appealing to exclusively liberal fears and values. Economic penalties, the loss of reputation in liberal institutions and calls to value human rights were meant to convince a man, with minimal respect for these, to act against his own interests.

This failure of understanding limits the ability of the West to successfully counter Russian action. How can you act against an objective when you were unable to understand it in the first place? Western analysis, with its reliance on the tools of diplomacy and soft coercion, has forgotten that when soft power fails, hard power must be a credible threat. After years of managed decline, how much of a deterrent are our increasingly degraded militaries? As long as the West prioritises soft power values over hard power realities, nations who do the opposite are free to act how they may.

Russia’s attempt to reassert itself as a Great Power has been a project decades in the making. Since Putin’s ascendency to power, Russia has reached the fourth-highest military expenditure in the world; made consistent and escalating interventions in Chechnya, Georgia and Syria; enacted an increasing clampdown on dissidents; and built up a significant currency reserve. Putin’s stated belief that the fall of the Soviet Union was “the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the century” was not born of any commitment to communist politics, but spoke to the decline of Russian influence over its neighbours in the post-Soviet years that followed. Putin wishes to make Russia a Great Power that can intervene and win abroad, prop up its allies and exterminate its ideological allies on foreign ground, without fear of diminishment on the world stage.

Putin’s ambition to gather together “Russian” lands has been clear for almost two decades now. His growing nationalist rhetoric and action over the past decade should have only indicated that this ambition was strengthening. That he had interventionist, even imperial, geopolitical goals should have come as a surprise to precisely none. He has long been open about those he admires (Peter the Great), those he despises (late and post-Soviet leadership) and his opinion of Russia’s rightful place in the world (ascendant).

Francis Turner offers the first sensible explanation of the lack of Russian airpower over the Ukraine that has been puzzling experts since the very start of the war:

Everyone knows that old quote that “amateur generals study tactics, professional ones study logistics”

Well, apparently that does not apply to the Russian high command, who seem to have failed to study logistics. I admit I didn’t see this coming, but then, as I said in my last post I am not a military expert and I kind of assumed that, while Russia might have a day or two of confusion as the initial “go in fast and topple the leadership” strategy is replaced by “go slower and more methodically”, it would adjust and continue to press forward.

I appear to have been wrong in that assumption.

First, what may seem like a slight detour, many people have noted Russia’s lack of air superiority. One reason for that could be that the Ukrainians have captured Russian mobile air defense systems in full working order. Which means they have complete lists of IFF signals, scheduled changes, cryptography settings etc. etc. Now potentially the Russians can change them, but they cannot change them via a radio broadcast because the Ukrainians will listen, so the only way to do an update is via soldiers on the ground hand delivering the updates (yes they could use land lines for some of the journey, but eventually they have to download them from some computer (print them out? copy to a USB drive?) and take them to the actual piece of equipment. Which takes time. Particularly since the vehicles doing the hand delivery have to share the roads with other parts of the Russian invasion force. But as the first link in the paragraph speculates another reason could be that the Russian airforce can’t actually coordinate things so that Ukrainian air defense systems can be targeted as they defend key sites against other Russian air attacks.

Failure to be able to take out Ukrainian air defenses is, IMHO, a symptom either way and it contributes to the bigger logistics issue because it means that the only way Russian forces can get resupply is on the ground, particularly since they can’t hold Hostomel airport either.

So logistics. Nitay Arbel posted this fascinating video about how Russians do logistics in Russia (they use the railways) and how that doesn’t work in Ukraine (Ukraine has trashed all cross border rail links). So the Russians need to use trucks. This was known and the consequences/limitations of that (should have been) entirely predictable, yet the Russians seem to not figured it all out in advance and been taken by surprise. Trent Talenko has a blog post and many tweet threads about how, particularly in the inland/north of the country, the Russians have to keep their convoys on the roads and that’s a major problem.

Back in the 1970s and 80s, one of the big differences between NATO and NATO-adjacent western militaries and those of the Warsaw Pact (and those aligned with or primarily equipped by the Soviets) was the different ratio between “teeth” and “tail”. Soviet-equipped militaries emphasized the “teeth” — the tanks, the guns, the attack aircraft and helicopters, that were the striking edge of an army’s advance. NATO and other western powers were much less about the number of tanks/guns/aircraft as they were about having enough logistical backup to keep their smaller numbers of trigger-pullers fed, supported, and resupplied with ammunition. This meant to a civilian eye, Soviet armies had many more obvious combat-capable vehicles than their western equivalents. Soviet doctrine called for units to be “burned up” in combat rather than conserved even if it meant giving up territory. Soviet battle plans tended to assume an all-out attack would not need further backup, reinforcement, or re-supply, because it would either succeed completely or fail completely and further efforts would be through alternative attack paths using different formations.

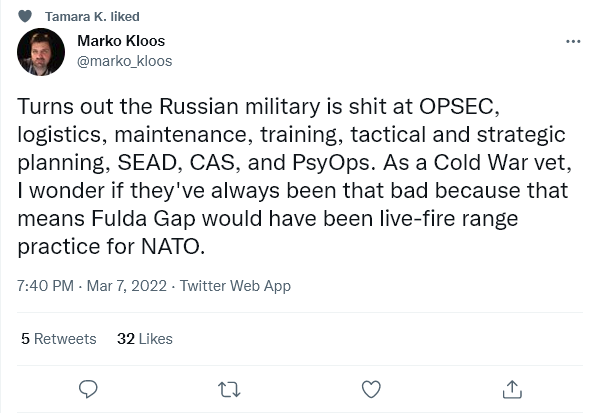

From what little we can definitely see in the current fighting in Ukraine, the Russian military is still much more Soviet in organization than it is “western”. As Marko Kloos put it on Twitter: