In City Journal, Ian Penman considers the paradox of Jim Morrison’s brief period of musical and cultural stardom yet seemingly endless echoes in popular culture:

Jim Morrison’s bright spotlight time with The Doors lasted not quite five years: the band’s debut album arrived in January 1967, and L.A. Woman, the final work to feature the singer, was released the week of his death, aged 27, on July 3, 1971.

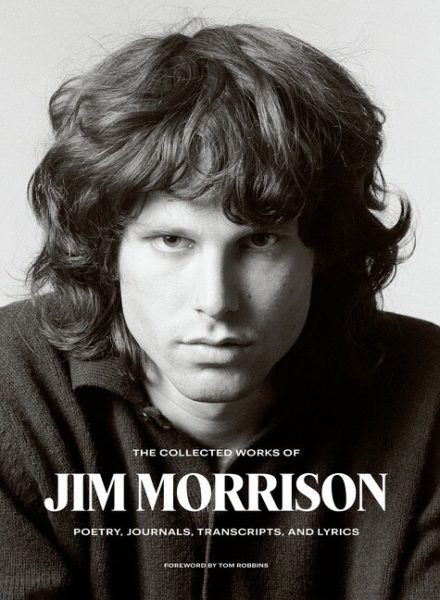

It’s now a half century since Morrison died in Paris in opaquely squalid circumstances, due to — take your pick — some mixture of alcohol, heroin, a small respiratory infection, and a general (not to say studied) carelessness. “When the music’s over / turn out the lights,” he sang in 1967, on The Doors’ second album, Strange Days. “Cancel my subscription / to the Resurrection.” Yet his revenant career as all-purpose Dionysian icon seems inexhaustible. From the posthumous album An American Prayer (1978) and The Doors’ soundtrack appearance on Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now (1979), to the serial publication of various “lost” Morrison writings and the lamentable Oliver Stone biopic The Doors (1991), there’s no medium that Morrison’s shade hasn’t found a way to inhabit. More recently, hip L.A. chanteuse Lana del Rey sang: “Living like Jim Morrison / Heading for a fucked-up holiday.” And now we have a figuratively and literally heavy 600-page tome, like a chic designer sarcophagus, with Harper’s publication of The Collected Works of Jim Morrison. Not designed for casual riffling, it should really come with its own lectern or pulpit. It’s hard to know whom this kind of swanky item is aimed at, but it’s a palpable attempt (in the current lingo) to secure Morrison’s legacy: to fix him as more than just this crazy dude who had a few glorious hits and looked sensational in leather pants.

What accounts for such a thriving afterlife? Why is there still such a halo around Morrison’s shaggy head when a cursory examination might suggest a fatally date-stamped cultural figure? How does this Nietzsche-quoting white bluesman and would-be shaman fit into today’s culturally disputatious landscape? A memory is being conjured, but is everything as straightforward as it looks?

Born in December 1943, the young James Douglas Morrison was the son of a career Navy man who bequeathed his firstborn son a middle name honoring no less a figure than General Douglas MacArthur. Constantly on the move from base to base with his family, with no real hometown or settled circle of friends, young James turned to books and music to forge a sense of self-possession. Pursuing the then-prevalent ethos of pop existentialism (via Camus, Nietzsche, and Genet) allowed Morrison to view his own deracinated life as a Sisyphean trial. Unlike many such adolescents, however, Morrison seems actually to have read all the key texts — and a lot more besides. He was particularly taken with doomed poets, demonology, and Greek myth.

This was a cultural moment between the declamatory Beats and rock and roll proper, with European authors all the rage in cheap, widely available paperbacks. The shy, pudgy, bookish James slowly became charismatic Jim in waiting, splicing together a wild strain of Rimbaud and Baudelaire, American blues and Native American shamanism. Such borrowings are likely to be chided these days for over-easy appropriation of other cultures; but at the time, it may have had less to do with privilege than a tentative questing for something larger than the self — less to do with the cliché of rebelling against conformity than a way of locating something to worship in a time and place that was big on prosperity but had little sense of the sacred. Morrison found it in American blues and European literature, and what eventually appeared was his own kind of two-headed soul music: The Doors’ debut album made space for covers of both Howlin’ Wolf’s “Back Door Man” and Brecht/Weill’s “Alabama Song”. Morrison opened a door onto a threshold space that he would call his “bright midnight”: a sublime European Romanticism transplanted to a very American plain of cars, bars, deserts, and beaches — The Golden Bough on the Billboard chart.

The founding myth of Morrison’s short, intense life occurred when he was only a child. In 1947, the four-year-old Morrison was on a family road trip somewhere in the desert between Albuquerque and Santa Fe, and they passed the scene of a horrific traffic accident, involving a truckload of Indian workers. He claimed that he felt the spirit of one of the dead Indians enter him and take up residence as storm clouds unfurled overhead: “Indians scattered on dawn’s hi-way bleeding / Ghosts crowd the young child’s fragile egg-shell mind.” This scene contains all the elements that he would later obsessively return to in song, poetry, and film. A car in motion. Blood, sand, and death. Ghost whispers and gigantic skies. Here is a liminal scene more real than the polite society he’s being raised in. Nothing quite so full of life for these young inquiring eyes as this moment of messy extinction. A primal landscape, with the figure of the bewildered but awakened man-child set against it: enormous horizons outside, the child’s intently fascinated gaze within. “It was the first time I discovered death.”