Anton Howes recounts some stories he uncovered while researching English patent and monopoly policies during the Elizabethan and Stuart eras:

… some of the most interesting proclamations to catch my eye were about tobacco. Whereas tobacco was famously a New World crop, it is actually very easy to grow in England. Yet what the proclamations reveal is that the planting of tobacco in England and Wales was purposefully suppressed, and for some very interesting reasons.

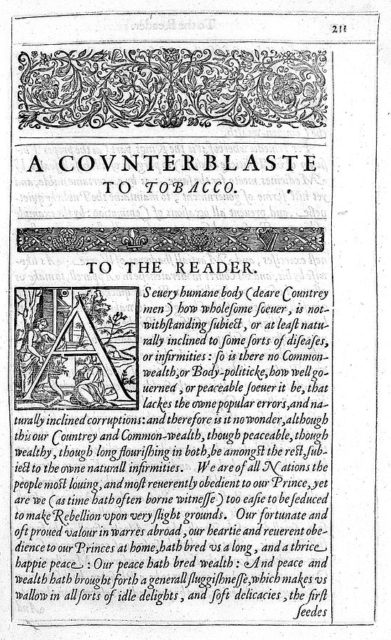

James I was an anti-tobacco king. He even published his own tract on the subject, A Counterblaste to Tobacco, just a year after his succession to the English throne. Yet as a result of his hatred of “so vile and stinking a custom”, imports of tobacco were heavily taxed and became a major source of revenue. Somewhat ironically, the cash-strapped king became increasingly financially dependent on the weed he never smoked. The emergence of a domestic growth of tobacco was thus not only offensive to the king on the grounds that he thought it a horrid, stinking, and unhealthy habit — it was also a threat to his income.

What I was most surprised to see, however, was just how explicitly the king admitted this. It’s usual, when reading official proclamations, to have to read between the lines, or to have to track down the more private correspondence of his ministers. Very often James’s proclamations would have an official justification for the public good, while in the background you’ll find it originated in a proposal from an official about how much money it was likely to raise. There was money to be made in making things illegal and then collecting the fines.

Yet the 1619 proclamation against growing tobacco in England and Wales had both. The legendary Francis Bacon, by this stage Lord High Chancellor, privately noted that the policy might raise an additional £3,000 per year in customs revenue. And the proclamation itself noted that growing tobacco in England “does manifestly tend to the diminution of our customs”. Although the proclamation notes that the loss of customs revenue was not usually a grounds for banning things, as manufactures and necessary commodities were better made at home than abroad, “yet where it shall be taken from us, and no good but rather hurt thereby redound to our people, we have reason to preserve”. Fair enough.

And that’s not all. James in his proclamation expressed all sorts of other worries about domestic tobacco. Imported tobacco, he claimed, was at least only a vice restricted to the richer city sorts, where it was already an apparent source of unrest (presumably because people liked to smoke socially, gathering into what seemed like disorderly crowds). With tobacco being grown domestically, however, it was “begun to be taken in every mean village, even amongst the basest people” — an even greater apparent threat to social order. James certainly wasn’t wrong about this wider adoption. Just a few decades later, a Dutch visitor to England reported that even in relatively far-flung Cornwall “everyone, men and women, young and old, puffing tobacco, which is here so common that the young children get it in the morning instead of breakfast, and almost prefer it to bread.”

[…]

Indeed, policymakers thought that the domestic production of tobacco would actively harm one of their key economic projects: the development of the colonies of Virginia and the Somers Isles (today known as Bermuda). Although James I hoped that their growth of tobacco would be only a temporary economic stop-gap, “until our said colonies may grow to yield better and more solid commodities”, he believed that without tobacco the nascent colonial economies would never survive. Banning the domestic growth of tobacco thus became an essential part of official colonial policy — one that was continued by James’s successors, who did not always share his more general hatred of smoking. Although the other justifications for banning domestic tobacco would soon fall away, that of maintaining the colonies — backed by an increasingly wealthy colonial lobby — was the one that prevailed.