In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes considers some alternative explanations for London’s spectacular growth beginning in the reign of Queen Elizabeth I:

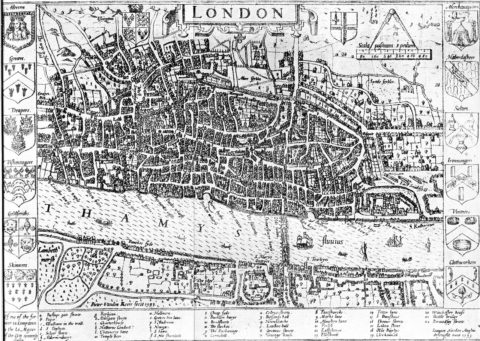

John Norden’s map of London in 1593. There is only one bridge across the Thames, but parts of Southwark on the south bank of the river have been developed.

Wikimedia Commons.

As regular readers will know, I’ve lately been obsessed with England’s various economic transformations between 1550 and 1650 — the dramatic eightfold growth of London, in particular, and the fall in the proportion of workers engaged in agriculture despite the growth of the overall population.

As I’ve argued before, I think that the original stimulus for many of these changes was the increased trading range of English overseas merchants. Thanks to advances in navigational techniques, they were able to find new markets and higher prices for their exports, particularly in the Mediterranean and then farter afield. And they were able to buy England’s imports much more cheaply, by going directly to their source. Although the total value of imports rose dramatically — by 150% in just 1600-38 — the value of exports seems to have risen by even more, as there’s plenty of evidence to suggest that for most of the period England had a trade surplus. The supply of money increased, even though Britain had no major gold or silver mines of its own.

The growing commerce was the major spur to London’s growth, with English merchants spending their profits in the city, and ever-cheaper and more varied luxury imports enticing the nobility from their country estates. Altogether, the concentration of people and wealth in London must have resulted in all sorts of spill-over effects to further drive its growth. After the initial push from overseas trade, I suspect that by the late seventeenth century the city was large enough that it was running on its own steam.

But on twitter, economic historian Joe Francis offered a slightly different narrative. Although he agrees that a change to overseas trade was the prime mover, he suggests that the trade itself was too small as a proportion of the economy to account for much of London’s growth. I disagree, for various reasons that I won’t go into now, but Joe brought to my attention various changes on the monetary side. Inspired by the work of Nuno Palma, he suspects that it was not the trade per se, but the fact of an export surplus that was doing the heavy lifting, by increasing the country’s money supply.

An increased money supply should have facilitated England’s internal trades, reducing their costs, and allowing for greater regional specialisation. Joe essentially thinks that I’ve got the mechanism slightly back to front: instead of London’s growing demands having reshaped the countryside, he contends that the specialisation of the entire country is what allowed for the better allocation of economic resources and workers to where they were most productive — a process from which a large city like London quite naturally then emerged.

I have some doubts about whether this process could really have been led from the countryside. The regional specialisation that we see in agriculture, for example, only really starts to become obvious from the 1600s onwards, by which stage London’s population had already begun to balloon from a puny 50,000 in 1550, to 200,000 and rising. I also haven’t found much evidence of other internal trade costs falling. Internal transportation — by packhorse, river, or down the coast — doesn’t seem to have become all that more efficient. Roads and waggon services don’t show much sign of improvement until the eighteenth century, and not many rivers were made more navigable before the mid-seventeenth century either. This is not to say that England’s internal trade didn’t increase. It certainly did, as London sucked in food and fuel in ever larger quantities, and from farther and farther afield. But it still looks like this was led by London demand, rather than by falling costs elsewhere.

Besides, the influxes of bullion from abroad would have all been channelled through London first, along with most of the country’s trade. To the extent that monetisation made a difference to the costs of trade then, this would have made a difference first in the city, before emanating out to its main suppliers, and then outwards. I thus see the Palma narrative as potentially complementary to my own.