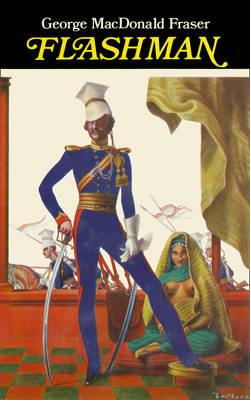

I happened upon a copy of the first Flashman in my teens and was totally taken in by the assertion that the book was about “a real historical figure involved in most of the Victorian era’s most notorious episodes and that his papers were discovered during a sale of household furniture at Ashby, Leicestershire in 1965.” I’d watched the TV adaptation of Tom Brown’s Schooldays, so I had some awareness about the character Flashman, which only helped keep the cover story going for me. I absolutely loved the book and while it eventually became clear that it was fiction, I haunted the bookshops for years afterwards searching for more from Fraser. In The Critic, Alexander Larman looks at the author and his works — which almost certainly could never have been published in this neo-Victorian age:

When Flashy first entered the scene in bestselling form in 1969, there was confusion as to whether the tales were fanciful fiction or eyebrow-raising fact. This was due to MacDonald Fraser’s straight-faced claim that his protagonist was a real historical figure involved in most of the Victorian era’s most notorious episodes and that his papers were discovered during a sale of household furniture at Ashby, Leicestershire in 1965.

MacDonald Fraser presented himself as an impartial editor. He wrote, “I have no reason to doubt that it is a completely truthful account; where Flashman touches on historical fact he is almost invariably accurate, and readers can judge whether he is to be believed or not on more personal matters.”

The subterfuge succeeded. A third of the initial reviews treated it as a serious work of non-fiction, rather than a brilliantly conceived and superbly written counter-factual piece.

Not bad for the continued exploits of a minor character in the sanctimonious Victorian novel Tom Brown’s Schooldays, whose major achievement is to bully the protagonist and his friend Harry “Scud” East, before being expelled for drunkenness. It set its creator on a hugely lucrative path, and established him as one of the great comic novelists of his day.

MacDonald Fraser was a contradictory figure. A patriotic right-winger who had a deep respect for other cultures and peoples; one of Hollywood’s most in-demand screenwriters who happily lived on the Isle of Man in a self-conscious recreation of “the good old days”; a fully paid-up reactionary who wished to reintroduce corporal and capital punishment, but who loathed British incursions abroad.

Above all, he despised cant and hypocrisy. He described Tony Blair as “not just the worst prime minister we’ve ever had, but by far the worst prime minister we’ve ever had” and angrily added, “it makes my blood boil to think of the British soldiers who’ve died for that little liar.”

Christopher Hitchens, who may not have agreed with his views on foreign expeditions, but knew a thing or two about the value of being able to hold one’s drink, was a friend of MacDonald Fraser’s. When Hitchens telephoned him on his eightieth birthday to offer his regards, he was stoutly informed that he shared the company of “Charlemagne, Casanova, Hans Christian Andersen and Kenneth Tynan” on that date.

Their politics may have differed — Christopher acknowledged MacDonald Fraser’s “robust Toryism” — but Hitchens respected the older writer’s enduring affection for his Zulu, Sikh and Afghan characters, as well as the dutiful admiration he showed towards both American culture and its presidents.