Scotland has had legal minimum prices for alcoholic beverages since mid-2018. If you read a random selection of mainstream media coverage, you’d know that it’s been a huge success, with vastly improved public health results at a price to consumers measured in mere pennies. As with all propaganda efforts, if you tell the lies often enough, people may believe you:

There has been all sorts of rubbish written about minimum pricing since it was introduced in Scotland in May 2018. Nicola Sturgeon has lied about in the Scottish Parliament. The BBC has gone to extraordinary lengths to spin the policy as a success. The public have been told that alcohol-related hospital admissions have gone down when they have gone up. We have seen the media fall for blatant cherry-picking. We have been told that rates of problem drinking have gone down when we don’t have any evidence either way.

One of the few solid facts — that there were more alcohol-related deaths recorded in Scotland in 2018 than in 2017 — has been sidelined. Instead, the media have focused on a disputed, and relatively small, decline in alcohol sales as if that were an end in itself. Any port in a storm (fortified wine sales have definitely benefited from minimum pricing).

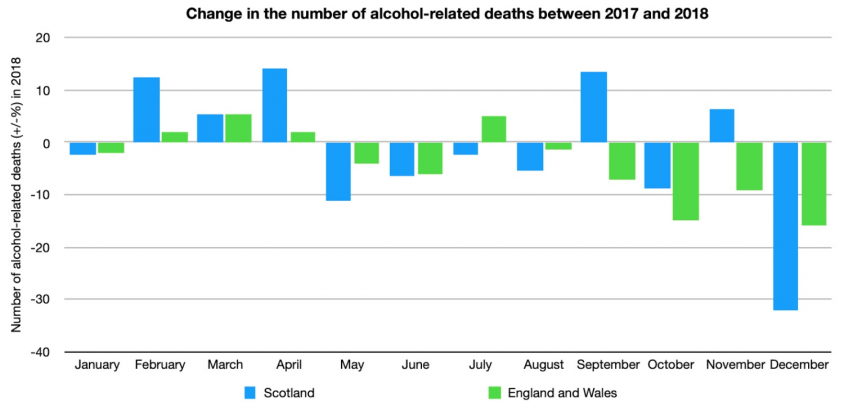

Figures from the calendar year of 2018 are of limited use because minimum pricing didn’t begin until May 1st. Today, for the first time, I can reveal the monthly mortality figures for Scotland, England and Wales. They show that there was no difference between the change in annual death rates from alcohol-related causes, regardless of whether the country had minimum pricing in place. Both England/Wales and Scotland saw a decline between May and December of seven per cent (compared to the previous year).

This graph is published in a new briefing paper I have written for the IEA. It summarises all the evidence gathered to date on deaths, hospitalisations and sales, plus exclusive new data.

Importantly, it contains estimates of the costs to consumers. Among the more outlandish claims made by the Sheffield modellers was the idea that moderate and low income consumers would be barely affected by minimum pricing. They predicted that a low income moderate drinker would only pay an extra 4p a year! This was never realistic, not least because it was based on the minimum price being set at 45p and they defined a moderate drinker as someone consuming the equivalent of just two pints of lager a week, but it worked from a PR perspective because it quelled politicians’ fears about the policy being regressive.