What saved them was abandoning the “common property” communalism and adopting private ownership of the farms:

The first few years of the settlement were fraught with hardship and hunger. Four centuries later, they also provide us with one of history’s most decisive verdicts on the critical importance of private property. We should never forget that the Plymouth colony was headed straight for oblivion under a communal, socialist plan but saved itself when it embraced something very different.

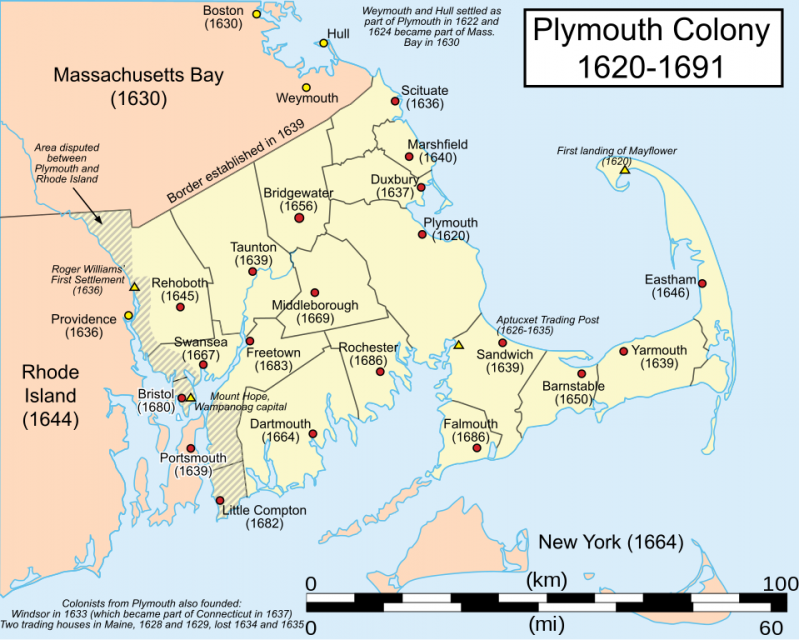

In the diary of the colony’s first governor, William Bradford, we can read about the settlers’ initial arrangement: Land was held in common. Crops were brought to a common storehouse and distributed equally. For two years, every person had to work for everybody else (the community), not for themselves as individuals or families. Did they live happily ever after in this socialist utopia?

Hardly. The “common property” approach killed off about half the settlers. Governor Bradford recorded in his diary that everybody was happy to claim their equal share of production, but production only shrank. Slackers showed up late for work in the fields, and the hard workers resented it. It’s called “human nature.”

The disincentives of the socialist scheme bred impoverishment and conflict until, facing starvation and extinction, Bradford altered the system. He divided common property into private plots, and the new owners could produce what they wanted and then keep or trade it freely.

Communal socialist failure was transformed into private property/capitalist success, something that’s happened so often historically it’s almost monotonous. The “people over profits” mentality produced fewer people until profit — earned as a result of one’s care for his own property and his desire for improvement — saved the people.

Over the centuries, socialism has crash-landed into lamentable bits and pieces too many times to keep count — no matter what shade of it you pick: central planning, welfare statism, or government ownership of the means of production. Then some measure of free markets and private property turned the wreckage into progress. I know of no instance in history when the reverse was true — that is, when free markets and private property produced a disaster that was cured by socialism. None.

A few of the many examples that echo the Pilgrims’ experience include Germany after World War II, Hong Kong after Japanese occupation, New Zealand in the 1980s, Scandinavia in recent decades, and even Lenin’s New Economic Policy of the 1920s.