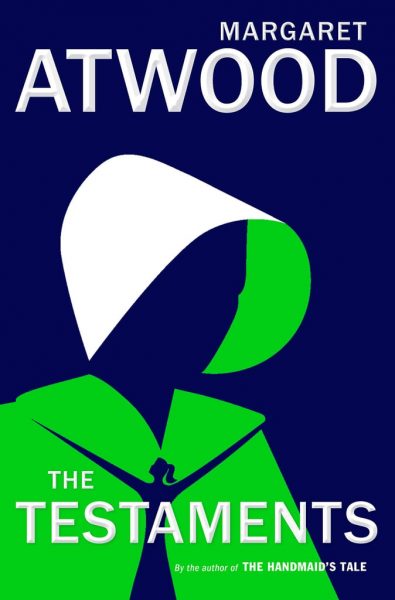

Colby Cosh discusses the genesis of Atwood’s best-known work from 1984, The Handmaid’s Tale and the new sequel published this week, The Testaments:

In a CBS interview broadcast on Sunday, Atwood insisted again, as she always has, that her book wasn’t a prediction. People who read her book in a spirit of active dread, the kind of people who dress up as Handmaids and march on legislatures, will say that, well, dystopias are created specifically so that they won’t come true. What Atwood is trying to say goes deeper than that, and contradicts it. She won’t even insist that the book was intended as a warning. “I’m not a prophet,” she pleads, while everyone around her tells her what a terrific prophet she is.

What she means, but cannot say because it would sound arrogant, is: “I’m not a prophet, dammit, I’m an artist.” If tyrannies were easy to predict and prevent by spritzing around a bit of literary bug spray, they couldn’t come about in the first place. Atwood knows better than this; she knows that tragedies of this scale never take the form that an author might anticipate. Moreover, people who read The Handmaid’s Tale as a mere tract are deaf to its satirical elements — particularly those of the epilogue, in which the story is revealed to have been unearthed by scholars in a still-more-distant future.These people are also failing to see that The Handmaid’s Tale is a book — researched, not merely imagined — about the past of humankind. The whole book is predicated on the observation (also made implicitly in Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four) that totalitarian regimes are never libertine; they all police sexuality at least as strenuously as they do trade and creative activity, and always come with puritanical, sexually homogenizing features. The novel was heavily influenced by Ceausescu’s Romania and its pro-natalist Decree 770, which abolished contraception and imposed mass gynecological inspection on women of fertile age. Europeans and students (or veterans) of the Cold War will notice this, but how many of the young folk who dress up as Handmaids at protests have any idea? (Are some of them also cosplaying on Twitter as postmodern retro-communists?)

I am curious to see what the critics make of the sequel, because the act of writing one seems a bit cynical, and yet perhaps Atwood has found some clever way of making it work. Offred’s narrative in The Handmaid’s Tale is, as I say, unearthed in a later future; it is important to the functioning of the book that we come to see her as a figure from the past, a human voice whose plea from an obscure period has been flung forward into the hands of half-comprehending and unsympathetic scholarly boobs.