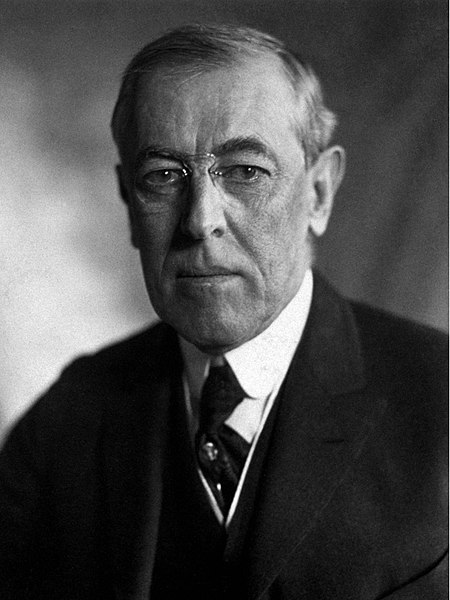

Michael Filozof on the hundred-year anniversary of the Treaty of Versailles and the American President who had so much to do with the casting of the treaty:

Eight months after committing troops to war, Wilson cobbled together a list of progressive war aims in his Fourteen Points. They demanded an end to secret deals (i.e., the Treaty of London and the Sykes-Picot Agreement); “ethnic self-determination” for Poland and Austro-Hungarian territories that would soon become Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia; “a free, open-minded, and absolutely impartial adjustment of all colonial claims,” and finally, a collective security organization, the League of Nations, which would be formed by a “covenant” (using the biblical term for a pact with God Himself) to maintain peace and territorial security of all nations.

Upon reading the Fourteen Points, French prime minister George “the Tiger” Clemenceau is said to have sniggered, “God gave us only ten.”

In 1919, Wilson became the first sitting president to venture overseas, practically abandoning his domestic duties and spending six months at the Paris Peace Conference personally negotiating the Treaty of Versailles. He was joined by “The Inquiry,” a group of over 100 academics and professors who surely knew how to fix the world and usher in Wilson’s global utopia.

Initially, Wilson and his Fourteen Points were wildly popular. He was greeted as if he were a latter-day rock star in France and Italy. Delegations from ethnic groups around the world came to Paris to beg Wilson for “self-determination.” (His French and British counterparts, Clemenceau and David Lloyd George, sneered that Wilson “thought he was Jesus Christ.”)

But they were soon to be disappointed. Wilson’s aims were so grandiose that they could not possibly be fulfilled. Italians, who had switched sides in the war to gain territory on the Dalmatian coast, became disillusioned when Wilson refused to accede to Italian demands. The negotiators did create Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Yugoslavia, but all three were destined to become communist dictatorships, and the latter two failed to outlast the twentieth century.

Worst of all was Wilson’s hypocrisy when it came to dealing with Germany. Wilson had railed against German imperialism, but turned a blind eye to the biggest empire at the Conference: Great Britain. A pro-British bigot, Wilson was contemptuous of Irish demands for self-determination and had been disgusted by the Easter Rising of 1916. Wilson granted Britain and France Ottoman territories they had secretly agreed to divvy up in the Sykes-Picot agreement — not as “colonies,” but under the guise of League of Nations “mandates.” He willingly partitioned Germany into two non-contiguous territories, separated by the Polish Corridor, and placed millions of ethnic Germans in the newly created nation of Czechoslovakia and the Free City of Danzig.

On a slightly lighter note, Al Stewart’s “A League of Notions” does a wonderful job of capturing the machinations at Versailles: