Alec Stapp reviews a new book by Tim Wu which contends that big business in the US is going to enable the rise of fascism just as it did in Germany in the 1930s … except that wasn’t how it happened in the Weimar Republic:

The recent increase in economic concentration and monopoly power make the United States “ripe for dictatorship,” claims Columbia law professor Tim Wu in his new book, The Curse of Bigness. With the release of Senator Elizabeth Warren’s proposal to “break up” technology companies like Amazon and Google, fear of bigness is clearly on the rise. Professor Wu’s book adds a new dimension to that fear, arguing that cooperation between political and economic power are “closely linked to the rise of fascism” because “the monopolist and the dictator tend to have overlapping interests.” Economist Hal Singer calls this the book’s “biggest innovation.”

The argument is provocative, but wrong. As I show below, the claim that big business contributed to the rise of the Nazi Party is simply inconsistent with the consensus among German historians. While there is some evidence industrial concentration contributed in Hitler’s ability to consolidate power after he was appointed chancellor in 1933, there is no evidence monopolists financed Hitler’s rise to power, and ample evidence showing industry leaders opposed his ascent.

Thomas Childers, a professor of history at the University of Pennsylvania, calls the idea that Hitler was bankrolled by big corporate donors a “persistent myth.” This, among myriad other reasons, should give us pause before comparing 1930s Germany to the present-day United States. If fascism does come to the United States, big business won’t be to blame.

[…]

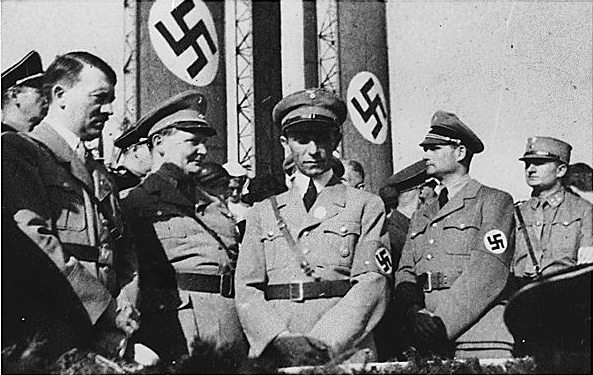

In the run-up to the presidential election in the spring of 1932, Hitler gave a speech to “a gathering of some 650 members of the Düsseldorf Industry Club in the grand ballroom of Düsseldorf’s Park Hotel.” British historian Sir Ian Kershaw recounts the event in Hitler: A Biography (p. 224):

Hitler’s much publicized address … did nothing, despite the later claims of Nazi propaganda, to alter the skeptical stance of big business. The response to his speech was mixed. But many were disappointed that he had nothing new to say, avoiding all detailed economic issues by taking refuge in his well-trodden political panacea for all ills. And there were indications that workers in the party were not altogether happy at their leader fraternizing with industrial leaders. Intensified anti-capitalist rhetoric, which Hitler was powerless to quell, worried the business community as much as ever. During the presidential campaigns of spring 1932, most business leaders stayed firmly behind Hindenburg, and did not favour Hitler … The NSDAP’s funding continued before the ‘seizure of power’ to come overwhelmingly from the dues of its own members and the entrance fees to party meetings. Such financing as came from fellow-travellers in big business accrued more to the benefit of individual Nazi leaders than the party as a whole. Göring, needing a vast income to cater for his outsized appetite for high living and material luxury, quite especially benefited from such largesse. Thyssen in particular gave him generous subsidies, which Göring — given to greeting visitors to his splendrously adorned Berlin apartment dressed in a red toga and pointed slippers, looking like a sultan in a harem — found no difficulty in spending on a lavish lifestyle.

As Ralph Raico, a professor of history at Buffalo State College, points out, the aim of these “relatively minor subsidies” to particular Nazis “was to assure (the donors) of ‘friends’ in positions of power, should the Nazis enter the state apparatus.” In Hitler: Ascent, 1889-1939, German historian and journalist Volker Ullrich details the extent of the industrialists’ support for center-right parties during the time of the Düsseldorf speech (p. 292):

[T]he American historian Henry A. Turner and others following in his footsteps have corrected this outmoded narrative about the relationship between National Socialism and major German industry. By no means had the entire economic elite of the Ruhr Valley attended Hitler’s speech… The crowd’s reaction to Hitler was also by no means as positive as (Nazi Press Chief Otto) Dietrich’s report had its readers believe. When Thyssen concluded his short word of thanks with the words “Heil, Herr Hitler,” most of those in attendance found the gesture embarrassing. Hitler’s speech also did little to increase major industrialists’ generosity when it came to party donations. Even Dietrich himself admitted as much in his far more sober memoirs from 1955: “At the ballroom’s exit, we asked for donations, but all we got were some well-meant but insignificant sums. Above and beyond that there can be no talk of ‘big business’ or ‘heavy industry’ significantly supporting, to say nothing of financing, Hitler’s political struggle.” On the contrary, in the spring 1932 Reich presidential elections, prominent representatives of industry like Krupp and Duisberg came out in support of Hindenburg and donated several million marks to his campaign.

The period immediately following Hitler’s speech to the Düsseldorf Industry Club was similarly fruitless for fundraising, as Richard J. Evans, a professor of history at the University of Cambridge, describes in The Coming of the Third Reich (p. 245):

Neither Hitler nor anyone else followed up the occasion with a fund-raising campaign amongst the captains of industry. Indeed, parts of the Nazi press continued to attack trusts and monopolies after the event, while other Nazis attempted to win votes in another quarter by championing workers’ rights. When the Communist Party’s newspapers portrayed the meeting in conspiratorial terms, as a demonstration of the fact that Nazism was the creature of big business, the Nazis went out of their way to deny this, printing sections of the speech as proof of Hitler’s independence from capital. The result of all this was that business proved not much more willing to finance the Nazi Party than it had been before.

Hitler lost the spring 1932 presidential election to Hindenburg. But the Nazi party achieved a plurality of seats in parliament for the first time in the July 1932 elections. Unable to form a government without Nazi cooperation after yet another round of elections in November 1932, Hindenburg appointed Hitler chancellor on January 30, 1933. With Hitler now in power, things changed.

In a 2014 review, Larry Schweikart wrote:

Still, more than a few voices critical of such historical hanky-panky have been raised. Perhaps the most influential is that of Henry A. Turner, Jr., who has provided an accurate and verifiable history of the Weimar period in his German Big Business and the Rise of Hitler. Turner sensibly avoids class struggle as a theme and simply asks if big business liked Hitler. Did business leaders support him? Did they give him money? Turner concludes that they did not. Only “through gross distortion can big business be accorded a crucial, or even major, role in the downfall of the Republic” (p. 340). Turner claims that bias “appears over and over again in treatments of the political role of big business even by otherwise scrupulous historians” (p. 350).

In his own examination of the evidence, Turner looked at the correspondence of German business leaders, minutes of their meetings, and their contributions. While it might be reassuring for some to think that Hitler came to power through the financial support of a few evil businessmen, the facts are that most of the Nazis’ money came from the German people. Turner carefully discusses Hitler’s policy stances toward business. Hitler was always wary of alienating the businessmen, but his failure to present a clear, procapitalistic economic program made the corporate leaders all the more leery of him. Modern Marxists, quite naturally, would like to implicate capitalism in the Holocaust. But, of course, Hitler’s themes were those of Stalin and, in our own day, Gorbachev. Nazism, as Turner suggests but never makes sufficiently clear, resembled Marxism in many ways, including Jew-hatred and hostility to the individual. In any case, Turner’s book has completely refuted the accepted notions that German corporations supported Hitler.

H/T to Colby Cosh for the initial link.