Austin Bay looks at Turkey’s domestic political situation following the re-election of Recep Erdoğan’s Justice and Development Party:

The threat to Turkish democratic institutions is a man notoriously jealous of Ataturk, current president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. The snap election gave Erdoğan and his Justice and Development Party, AKP, overwhelming control of parliament (316 of 550 seats). The AKP had controlled parliament since 2002, but in the June 7 election it lost its one-party majority. Political haggling among opposition parties, including Ataturk’s Republican Peoples Party, the CHP, failed to produce a coalition government; a new election was necessary.

However, in the intervening month’s domestic terrorist incidents, the fitful war with the Islamic State in the Levant and Syria’s violent chaos dominated Turkish politics.

Erdoğan portrayed himself as the only leader capable of addressing Turkey’s deteriorating security situation. Domestic security certainly diminished; why it did stirs angry accusations. Erdoğan’s political opponents maintain that he used the violence to solidify political support. His more vicious critics accuse him of intentionally permitting violence. For example, they argue his government could have prevented the Oct. 10 terror bombing of a peace march in Ankara, now attributed to ISIL. Over 100 people were murdered in that attack.

Is it an over the top conspiracy theory-type accusation? Possibly. Erdoğan himself, however, believes over the top conspiracy theories, and he uses conspiratorial doubt and fear as political tools. His record for jailing journalists and intimidating political opponents associated with his alleged conspiracies is fact, not theory. The election didn’t assuage his fears — it ignited another surge of arrests. On Nov. 3, police arrested scores of people associated with Erdoğan critic and Muslim cleric Fethullah Gulen. At one time Gulen supported Erdoğan and the moderate Islamist AKP. However, Gulen broke with Erdoğan over credible charges of corruption within Erdoğan’s governing circle.

Daniel Pipes isn’t convinced that the terror stampeded voters in Erdoğan’s direction (especially Kurdish voters), and he suspects fraud in the election results:

Like other observers of Turkish politics, I was stunned on November 1 when the ruling Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi, or AKP) was reported to have increased its share of the national vote since the last round of elections in June 2015 by 9 percent and its share of parliamentary seats by 11 percent.

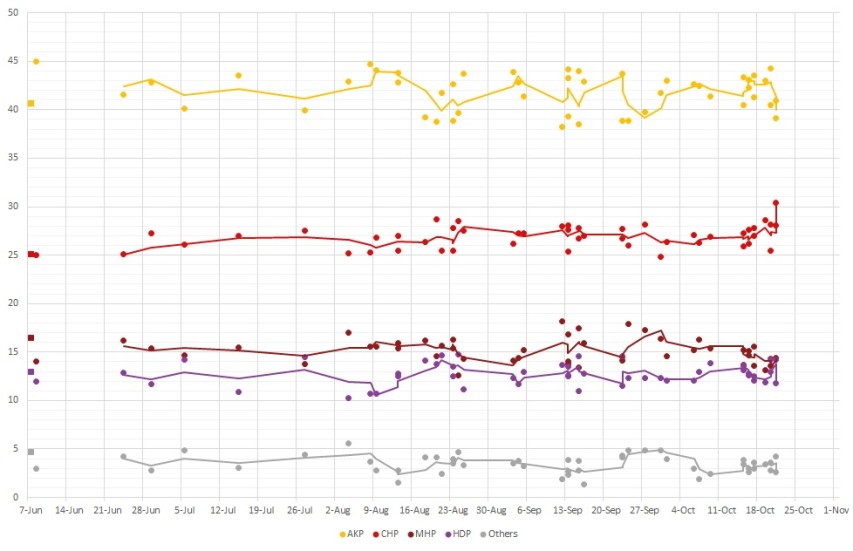

The polls had consistently shown the four major parties winning about the same number of seats as in June. This made intuitive sense; they represent mutually hostile outlooks (Islamist, leftist, Kurdish, nationalist), making substantial movement between them in under five months highly unlikely. That about one in nine voters switched parties defies reason.

Polling results between the June and November 2015 Turkish elections

The AKP’s huge increase gave it back the parliamentary majority it had lost in the June 2015 elections, promising President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan a semi-legal path to the dictatorial powers he aspires to.

But, to me, the results stink of fraud. It defies reason, for example, that the AKP’s war on Kurds would prompt about a quarter of Turkey’s Kurds to abandon the pro-Kurdish party and switch their votes to the AKP.