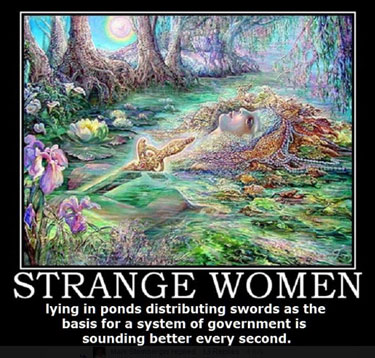

H/T to Never Yet Melted for the graphic.

In Kirkus, Andrew Liptak talks about the early publishing experiences of Lois McMaster Bujold:

In the 1970s, science fiction began to fragment into smaller subsets: the New Wave fizzled out, leaving its own imprint on the genre, while new subgenres grew in the aftermath. One author of the time looked back to her roots for inspiration for her stories, developing her own brand of science fiction that at once revered the classics of the genre while using the same building blocks to subvert them.

Lois McMaster Bujold was born in Columbus, Ohio, on November 2, 1949. Her father, Robert Charles McMaster, an engineering professor, was an avid reader of science-fiction magazines and stories and passed them along to his daughter. Throughout Bujold’s youth, she devoured every science-fiction novel she could get her hands on. In high school, she began writing along with a friend of hers, Lillian Stewart, and when she entered college in 1968, she began studying English. Her passion for the academic subject waned, but her “heart was in the creative, not the critical end of things.” According to Bujold’s official website, she noted that the New Wave “left me cold; I found it, much like the ‘alternative comics’ I encountered in my college years, to seem dreary, ugly, and angry.” From college, she went on to work as a pharmacy technician at the Ohio State University Hospital. She left to get married and had two children: good for reading, not for writing. Throughout this time, she read voraciously.

When her friend Lillian Stewart Carl published her first short story in 1982, Bujold found a renewed commitment to writing. In 1983, she completed her first novel, Shards of Honor, and an additional two in as many years: Warrior’s Apprentice and Ethan of Athos. Initially, major publishers rejected her unagented manuscripts. In an interview for the Baen Books website, Bujold said that “[Warrior’s Apprentice] had been rejected by Tor and Ace; on the advice of the Ace editor, who said it was a YA (Young Adult, what used to be called “Juvenile Fiction” back in my day — think early Heinlein), probably because the protagonist was 17, I sent it to YA publisher Atheneum, who plainly disagreed; the manuscript came back in about eight weeks.” Dejected, she spoke with friends about what her next step should be. Carl recommended that she send it to a recently founded publisher, Baen Books. Bujold followed her advice, and shortly thereafter, “in late October of 1985, was Jim Baen calling me on the phone, there in my kitchen in Marion, Ohio, and offering to buy all three volumes. I was completely flummoxed by the acceptance being a phone call; I would at the time have assumed any word would travel by mail.”

Published on 8 Feb 2015

In this video, we discuss how different markets are linked to one another. How does the price of oil affect the price of candy bars? When the price of oil increases, it is of course more expensive to transport goods, like candy bars. But there are other, more subtle ways these two markets are connected. For instance, an increase in the price of oil leads to an increase in demand for oil substitutes, like ethanol. And when the supply of oil falls, oil should shift to higher-valued uses. But, which uses? How do we decide where to use less oil?

This brings us to the great economic problem: how to most effectively arrange our limited resources to satisfy our needs and wants. Which approach — central planning or the price system — is better at solving this problem? Join us as we explore this question further.

Compound Interest posted an infographic on cannabis and synthetic cannabinoids:

In recent years, there’s been an increase in the number of media reports on users of synthetic cannabinoids. Commonly referred to by names such as ‘Spice’ or ‘K2′, the most recent reported case involved five UK students being hospitalised after use. But what are the chemicals present in ‘spice’ and similar drugs, and what are the chemical compounds in cannabis that they aim to mimic? That’s what this graphic and post attempt to answer.

In the small groups we evolved to live in, shame is tempered by love and forgiveness. People are shamed for some transgression, then they are restored to the group. Ultimately, the shamed person is not an enemy; he or she is someone you need and want to get along with. This is how you make up with your spouse after one or both of you has done or said something terrible.

In a large group, shame is punishment, but it still has a restorative aspect. One of the most surprising passages of Ronson’s book reveals that the drunken driver who had to stand by the side of the road with a sign detailing his crimes got more compassion and support than bitter catcalls from the people who drove by him.

On the Internet, when all the social context is stripped away and you don’t even have to look at the face of the person you’re being mean to, shame loses its social, restorative function. Shame-storming isn’t punishment. It’s a weapon. And weapons aren’t supposed to be used against people in your community; they’re for strangers, people in some other group that you don’t like very much.

Megan McArdle, “How the Internet Became a Shame-Storm”, Bloomberg View, 2015-04-17.

Powered by WordPress