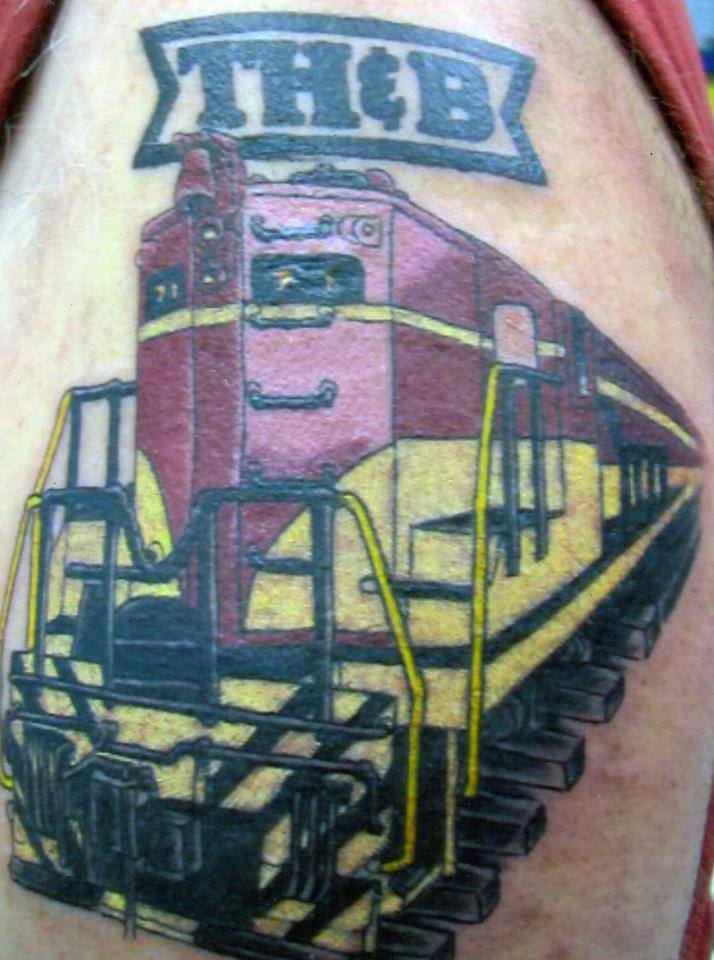

I mean, after all, I founded a historical society based on the study of the railway … but Mel McInnis puts me into the shade with his dedication to the old Toronto, Hamilton & Buffalo Railway:

February 23, 2015

I thought I was a fan of the old TH&B Railway…

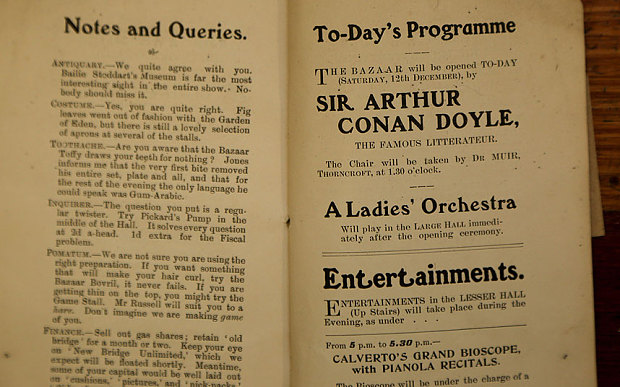

The mystery of the lost Sherlock Holmes short story

Tim Chester alerted me to the discovery of a short story contributed by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle to a fundraising effort to save a bridge in Selkirk:

A Scottish historian has discovered a lost Sherlock Holmes story in his attic, over 80 years after it was written by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

Walter Elliot found the 1,300-word tale featuring the famous detective — played on TV by Benedict Cumberbatch — in a collection of stories he was given over 50 years ago. It’s called Sherlock Holmes: Discovering the Border Burghs and, by deduction, the Brig Bazaar.

Elliot was given the 48-page pamphlet half a century ago by a friend, but forgot all about it until he was rooting around in his attic recently. It’s believed to be the first unseen Holmes story by Doyle since the last was published over 80 years ago.

The story is now available to read online.

A book, containing a short Sherlock Holmes story by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle is on display at the Selkirk Pop Up Community Museum after Walter Elliot, 80, found it in his attic and donated it.

You can read the story at the Telegraph.

The “Internet of Things” (That May Or May Not Let You Do That)

Cory Doctorow is concerned about some of the possible developments within the “Internet of Things” that should concern us all:

The digital world has been colonized by a dangerous idea: that we can and should solve problems by preventing computer owners from deciding how their computers should behave. I’m not talking about a computer that’s designed to say, “Are you sure?” when you do something unexpected — not even one that asks, “Are you really, really sure?” when you click “OK.” I’m talking about a computer designed to say, “I CAN’T LET YOU DO THAT DAVE” when you tell it to give you root, to let you modify the OS or the filesystem.

Case in point: the cell-phone “kill switch” laws in California and Minneapolis, which require manufacturers to design phones so that carriers or manufacturers can push an over-the-air update that bricks the phone without any user intervention, designed to deter cell-phone thieves. Early data suggests that the law is effective in preventing this kind of crime, but at a high and largely needless (and ill-considered) price.

To understand this price, we need to talk about what “security” is, from the perspective of a mobile device user: it’s a whole basket of risks, including the physical threat of violence from muggers; the financial cost of replacing a lost device; the opportunity cost of setting up a new device; and the threats to your privacy, finances, employment, and physical safety from having your data compromised.

The current kill-switch regime puts a lot of emphasis on the physical risks, and treats risks to your data as unimportant. It’s true that the physical risks associated with phone theft are substantial, but if a catastrophic data compromise doesn’t strike terror into your heart, it’s probably because you haven’t thought hard enough about it — and it’s a sure bet that this risk will only increase in importance over time, as you bind your finances, your access controls (car ignition, house entry), and your personal life more tightly to your mobile devices.

That is to say, phones are only going to get cheaper to replace, while mobile data breaches are only going to get more expensive.

It’s a mistake to design a computer to accept instructions over a public network that its owner can’t see, review, and countermand. When every phone has a back door and can be compromised by hacking, social-engineering, or legal-engineering by a manufacturer or carrier, then your phone’s security is only intact for so long as every customer service rep is bamboozle-proof, every cop is honest, and every carrier’s back end is well designed and fully patched.

Do these count as “known unknowns”? Searching for copies of the Magna Carta

At the Magna Carta Project, Professor Nicholas Vincent recounts how he tracked down a previously unknown copy in Sandwich:

Now, I have often found that the most interesting original records of Magna Carta, as of much else, have gone unnoticed precisely because they are assumed either to be copies rather than originals or because they travel with other less famous documents. Cataloguers, assuming that Magna Carta is much too important to have been overlooked, have very frequently assumed that originals are copies, not from any physical evidence of the fact, but simply because the idea of possessing an unknown Magna Carta has appeared to the cataloguer to be as absurd as suddenly stumbling upon an unknown play by Shakespeare or a unknown canvas by Vermeer. The most famous documents are often the documents that, in their natural habitat, have been least studied. Edgar Allan Poe sums up this situation perfectly in his story “The Purloined Letter”. Poe’s plot here turns on the fact that, if you wish to hide something that everybody else assumes hidden, the best place to hide it is in plain view.

I can claim, long before last December, to have found at least three Magna Cartas. All were in plain view. None of them was ‘unknown’, in the sense that they had all previously been listed, albeit in obscure places, either as Magna Cartas or as ‘copies’ of Magna Carta. They were nonetheless ‘unknown’ in the sense that they were either assumed to be ‘copies’ or ‘duplicates’ rather than originals (one of the three 1217 Magna Cartas, and the 1225 Magna Carta in the Bodleian Library in Oxford), or were known locally but without any appreciation that local knowledge had not come to national or international attention (the 1300 Magna Carta preserved in the archives of the borough of Faversham). In one instance (the 1217 Magna Carta now in Hereford Cathedral), it had been catalogued as a royal charter of liberties, but without realizing that these liberties were those otherwise known as ‘Magna Carta’. I vividly remember phoning Hereford Cathedral, in 1989, and asking if I could go down there the following day to see their Magna Carta (for there could be little doubt from the catalogue entry that Hereford’s ‘Charter of liberties 1217’ was a 1217 Magna Carta). I received a very dusty answer. ‘We have no Magna Carta’, I was told, ‘You must be thinking of Mappa Mundi!’. Ignoring this, and ordering up the document by call number, I found myself, the following morning, greeted on Hereford railway station by the canon librarian and the delightful cathedral archivist, Meryl Jancey. Archivists and canon librarians do not generally go to the railway to greet visiting postgraduate students. Short of playing me up Hereford High Street with a brass band, they could not have expressed more joy. And inevitably, their first question was ‘How much is it worth?’.The Hereford Magna Carta of 1217

[…]

One other detail before we pass on. Magna Carta as issued in 1215 promised reform not only of the realm as a whole but of the King’s administration of those parts of England placed under ‘forest law’ (i.e. set aside for the King’s hunting, with severe consequences for land use and the preservation of game). In 1217, to answer this demand for reform, King Henry III not only issued a new version of Magna Carta but, as a companion piece, an entirely distinct and smaller charter known as the ‘Forest Charter’. From 1217 onwards, the Forest Charter travelled in the company of Magna Carta, rather as a pilot fish accompanies a shark. It was in order to distinguish between these two documents, bigger and smaller, that as early as 1217 Magna Carta was first named ‘Magna’ (‘the great’). Thereafter, on each successive reissue of Magna Carta, the Forest Charter was also reissued, in 1225, 1265, 1297 and 1300. The Record Commissioners, in their search for original documents, were much less thorough in their treatment of the Forest Charter than they were in their search for its more famous sibling. Blackstone had found only two original Forest Charters, both of them very late. The Record Commissioners knew of only three. By contrast, we now know that at least twelve survive. Some of these turned up fortuitously at the time of my own search for new manuscripts in 2007. Others had resurfaced even more recently.So it was, that around 4.30am in the morning of 9 December 2014, I decided that a catalogue entry describing a Forest Charter of 1300, might well merit further investigation. Even in the seven years between 2007 (when I compiled my lists for Sotheby’s) and 2014, when I stumbled on the reference to the borough of Sandwich’s Forest Charter, I had found at least three further original Forest Charters previously misidentified or ignored. The earliest of these, of 1225, came to light amongst the muniments of Ely Cathedral, the most recent, of 1300, in the British Library. An original of 1300 at Oriel College seen by Blackstone, reported missing in 2007, had re-emerged safe and sound.

Thanks to modern technology, from Belfast to Maidstone is a mere click of the mouse. At 4.39 Greenwich meantime on the morning of 9 December last year, I sent an email (I have it in front of me) to Dr Mark Bateson. I have known Mark for nearly twenty years, first as an archivist at Canterbury Cathedral (where he was one of those who devised the magnificent catalogue of Canterbury’s medieval charters), and more recently following his transfer to Maidstone. I told him that I had found the reference to a Forest Charter , and as I noted in my email: ‘If this really is the 1300 Sandwich copy of the forest charter, issued under the seal of Edward I, then it is a major find. There are only a handful of such exemplifications still surviving as originals. It would also fundamentally alter our understanding of the way in which the charters of liberties were distributed for the later reissues of Magna Carta. Is there any chance of your taking a sneak preview?’

QotD: Why did people join the First Crusade?

Q: Why did people join the First Crusade?

A: The most common answer in Crusade scholarship — and you can tell I’m not going to accept it — is that the goal was penance and the opportunity to have sins forgiven. That’s not quite enough for me, because whenever we’re able to get as close as we can to knowing medieval warriors it looks like they’re not nearly as concerned with sin and penance and forgiveness as we would expect them to be. The king of France at the time of the Crusade was actually excommunicated because he was in a bigamist marriage. The pope excommunicated him, and he didn’t seem to care.

What I tried to emphasize in my book was that there was a real sense of prophetic mission among a lot of people who answered this call for Crusade. You can’t have a normal war for Jerusalem. That seems to me as true today as it would have been in the 11th century. Jerusalem, from the medieval Christian perspective, was both a city on earth and a city of heaven, and these two places were linked. The idea that the Jerusalem on earth was being dominated by an unbelieving, infidel — in their terminology “pagan” — group was unacceptable. The rhetoric that was associated with the people holding Jerusalem is pretty shocking: Christian men are being circumcised in baptismal fonts, and the blood is being collected! They’re yanking people’s innards out by their belly buttons! This is not normal talk. Hatreds and passions were stirred up. The heart of it, and why it was so successful, was that the call to Jerusalem was felt so strongly.

Virginia Postrel talking to Jay Rubenstein, “Why the Crusades Still Matter”, Bloomberg View, 2015-02-10.