Published on 4 Dec 2014

During the first week of December, Austria manages to capture Belgrade. Thereby Austria is the first nation to achieve one of its war aims. The victorious Austrians are joyful, but the Serbs strike back and the Austrian euphoria takes a sudden end. Meanwhile, the Russians fight against the German and Austrian troops in front of Cracow. But the Austrians are able to stop the Russian offensive and achieve yet another victory.

The atrocities, the Austrians committed in Serbia, were part of our episode from August 28, in which we are also talking about the so called Rape of Belgium, a series of atrocities committed by German troops in Belgium: http://bit.ly/1BhsysW

December 5, 2014

Mission Accomplished? – The Austro-Hungarian Empire Conquers Belgrade l THE GREAT WAR Week 19

The urban light-rail mania

If you live in a city, chances are that the politicians of your ‘burgh are talking light rail. Unless, of course, you already are suffering under the burden of a light rail project snarling traffic during construction … and snarling traffic in operation. Light rail, in general, is an attempt to resurrect the streetcar era by vast infusions of tax dollars. It’s an attempt to solve a traffic management problem in one of the more inefficient ways possible: to get a few people out of their cars and into modern streetcars instead.

I’m not anti-rail by any means. I travel five days a week on a heavy rail commuter train that does a pretty fair job of getting me where I need to go in a timely and economical fashion. Worse than that, I’m a railway fan — as I’ve mentioned before, I founded a railway historical society. I’m not against light rail due to some sort of anti-rail bias … I’m against it because it’s almost always too expensive, too inflexible, and too politicized.

Georgi Boorman wonders why so many cities are still falling into the light rail trap:

In a previous piece, I discussed the radical ideological roots of the mass transit scam. There are some, such as Seattle City Councilwoman Kshama Sawant (who urged Boeing factory workers to seize control of the plant and begin building mass transit) who believe centralization and a complete shift to mass transit are crucial for cities’ futures. Others simply buy into this myth that light rail and trolleys will somehow elevate their cities to the next level of sophistication — the very prospect of which is ignorant, at best, and self-indulgent, at worst.

The overwhelming evidence shows that these mass transit projects do little to improve our quality of life, in terms of easing congestion and expanding access to jobs and, despite popular perception, have no significant net environmental benefits since they rarely succeed in their express goal of removing cars from the road or decreasing congestion-induced idle times, a frequently cited contributor to greenhouse-gas emissions. As the satirical online newspaper The Onion reported, “98% of Americans favor public transportation for others.” That statistic may be fake, but we’ve all experienced the sentiment.

Even the writers of The Simpsons seem to understand the comical nature of light-rail adoption in American cities, brilliantly satirizing the salesmanship by transit authorities. The salesman, “Lyle Lanley,” begins by comparing the Simpsons’ town of Springfield to Shelbyville. “This is more of a Shelbyville idea,” he says slowly, turning his back to the crowd. “Now, wait a minute!” the Springfield mayor responds hastily, “We’re just as smart as the people of Shelbyville—just tell us your idea and we’ll vote for it!”

Gleefully, Lanley begins his presentation; with a grand sweeping gesture, the salesman uncovers a model of the city, complete with buildings, trees, and a brand new Springfield Monorail zooming through the town on its miniature tracks. Holding up a map labeled with all the towns to which he’s sold monorails, he exclaims, “By gum, it put them on the map!” Continuing his pitch, Langley heightens the townspeople’s imaginations and sells them on the “novel” idea of their very own monorail.

In other words, the buy-in had nothing to do with demand for a certain kind of transportation, and everything to do with wanting do the same as other cities that have, or are building, the same thing. Of course, 50 years ago the Seattle Center monorail (built by the German company Alweg) could easily have been said to have elevated the Emerald City at the 1962 World’s Fair, being the cutting-edge of rail technology at the time; but building monorails, light rails, and streetcars in 2014 is a regressive move that mirrors the past rather than engages with the present while leaving room for future innovation.

For our next trick, we need to crack another genetic code

Michael White says we need to follow up our success in reading our own genetic code by decoding a different one:

There are thousands of mutations that occur in the breast cancer-linked genes BRCA1 and BRCA2. Some of these cause breast or ovarian cancer, while others are harmless. When we design a genetic test for predisposition to breast cancer, we have to know which ones to test for. The same is true of almost any gene that plays a role in disease — you’ll find many mutations in that gene in the general population, only some of which cause health problems. So how do we know which mutations to worry about?

We start by using the genetic code. The genetic code, cracked by scientists in the 1960s, makes it surprisingly easy to “read” our DNA and understand how a particular mutation affects a gene. As genetic testing takes on a bigger role in predicting, diagnosing, and treating disease, we rely on this code to help us make sense of the data. Unfortunately, the genetic code applies to less than two percent of our DNA. In an effort to read the rest, researchers are trying to crack a new genetic code — and this next one is turning out to be much more difficult to solve than the first. In fact, scientists may have to give up the idea that we can use a “code” to “read” the rest of our DNA.

When scientists were working out the original genetic code in the 1950s and ’60s, all sorts of complicated schemes were proposed to explain how information is stored in our genes. The problem they were trying to solve was how a gene, made of DNA, codes the information to make a particular protein — an enzyme, a pump, a piece of cellular scaffolding, or some other critical component of the cell’s working machinery. They were looking for a code that would translate the four-letter DNA alphabet of genes into the 20-letter amino acid alphabet of proteins.

[…]

Thanks to its simplicity, the genetic code is a powerful tool in our hunt for mutations that cause disease. Unfortunately, it has also led to the genetic equivalent of a drunk looking for his lost keys under the lamppost. Researchers have put much of their effort into looking for disease mutations in those parts of our genomes that we can read with the genetic code — that is, parts that consist of canonical genes that code for proteins. But these genes make up less than two percent of our DNA; much more of our genetic function is outside of genes in the relatively uncharted “non-coding” portions. We have no idea how many disease-causing mutations are in that non-coding portion — for some types of mutations, it could be as high as 90 percent.

Ross Perot (of all people) and one of the earliest real computers

At Wired, Brendan I. Koerner talks about the odd circumstances which led to H. Ross Perot being instrumental in saving an iconic piece of computer history:

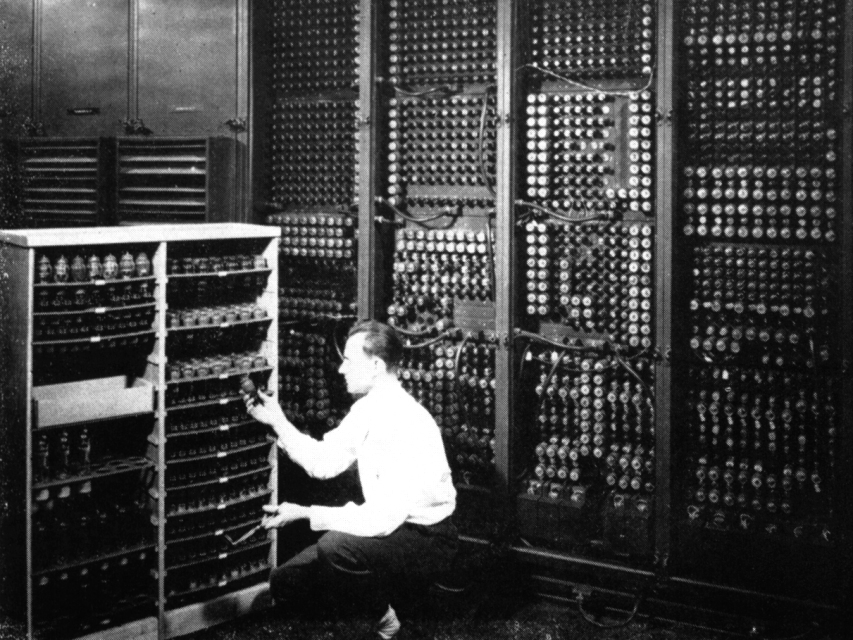

Eccentric billionaires are tough to impress, so their minions must always think big when handed vague assignments. Ross Perot’s staffers did just that in 2006, when their boss declared that he wanted to decorate his Plano, Texas, headquarters with relics from computing history. Aware that a few measly Apple I’s and Altair 880’s wouldn’t be enough to satisfy a former presidential candidate, Perot’s people decided to acquire a more singular prize: a big chunk of ENIAC, the “Electronic Numerical Integrator And Computer.” The ENIAC was a 27-ton, 1,800-square-foot bundle of vacuum tubes and diodes that was arguably the world’s first true computer. The hardware that Perot’s team diligently unearthed and lovingly refurbished is now accessible to the general public for the first time, back at the same Army base where it almost rotted into oblivion.

ENIAC was conceived in the thick of World War II, as a tool to help artillerymen calculate the trajectories of shells. Though construction began a year before D-Day, the computer wasn’t activated until November 1945, by which time the U.S. Army’s guns had fallen silent. But the military still found plenty of use for ENIAC as the Cold War began — the machine’s 17,468 vacuum tubes were put to work by the developers of the first hydrogen bomb, who needed a way to test the feasibility of their early designs. The scientists at Los Alamos later declared that they could never have achieved success without ENIAC’s awesome computing might: the machine could execute 5,000 instructions per second, a capability that made it a thousand times faster than the electromechanical calculators of the day. (An iPhone 6, by contrast, can zip through 25 billion instructions per second.)

When the Army declared ENIAC obsolete in 1955, however, the historic invention was treated with scant respect: its 40 panels, each of which weighed an average of 858 pounds, were divvied up and strewn about with little care. Some of the hardware landed in the hands of folks who appreciated its significance — the engineer Arthur Burks, for example, donated his panel to the University of Michigan, and the Smithsonian managed to snag a couple of panels for its collection, too. But as Libby Craft, Perot’s director of special projects, found out to her chagrin, much of ENIAC vanished into disorganized warehouses, a bit like the Ark of the Covenant at the end of Raiders of the Lost Ark.

Lost in the bureaucracy

QotD: The art of political leadership

[A politician’s] ear is ever close to the ground. If he is an adept, he can hear the first murmurs of popular clamour before even the people themselves are conscious of them. If he is a master, he detects and whoops up to-day the delusions that the mob will cherish next year.

H.L. Mencken, Notes on Democracy, 1926.