Published on 13 Nov 2014

The German army dug in at the Western Front and waited for the next enemy attack at the Eastern Front. Even though the Germans outnumbered their opponents, they barely stand a chance against machine guns in no-man’s-land. But they realize: to defend a position is a lot easier than to attack and conquer. Especially while fighting near Ypres. At the Eastern Front, things are going better for Chief of Staff Ludendorff: he breaks through outstretched Siberian lines. At the same time, Russian soldiers are faced with a new enemy and start the Bergmann Offensive in today’s East-Turkey.

November 14, 2014

Defend, Don’t Strike! – The Defensive War I THE GREAT WAR Week 16

Either kink is now pretty much mainstream … or Quebec is a hotbed of kinksters

In Reason, Elizabeth Nolan Brown reviews the findings of a recent survey on what kind of kinks are no longer considered weird or unusual (because so many people fantasize about ’em or are actively partaking of ’em):

Being sexually dominated. Having sex with multiple people at once. Watching someone undress without their knowledge. These are just a few of the totally normal sexual fantasies uncovered by recent research published in the Journal of Sexual Medicine. The overarching takeaway from this survey of about 1,500 Canadian adults is that sexual kink is incredibly common.

While plenty of research has been conducted on sexual fetishes, less is known about the prevalence of particular sexual desires that don’t rise to the level of pathological (i.e., don’t harm others or interfere with normal life functioning and aren’t a requisite for getting off). “Our main objective was to specify norms in sexual fantasies,” said lead study author Christian Joyal. “We suspected there are a lot more common fantasies than atypical fantasies.”

Joyal’s team surveyed about 717 Québécois men and 799 women, with a mean age of 30. Participants ranked 55 different sexual fantasies, as well as wrote in their own. Each fantasy was then rated as statistically rare, unusual, common, or typical.

Of course, the statistics also show where men and women differ in some areas:

Notably, men were more likely than women to say they wanted their sexual fantasies to become sexual realities. “Approximately half of women with descriptions of submissive fantasies specified that they would not want the fantasy to materialize in real life,” the researchers note. “This result confirms the important distinction between sexual fantasies and sexual wishes, which is usually stronger among women than among men.”

The researchers also found a number of write-in “favorite” sexual fantasies that were common among men had no equivalent in women’s fantasies. These included having sex with a trans woman (included in 4.2 percent of write-in fantasies), being on the receiving end of strap-on/non-homosexual anal sex (6.1 percent), and watching a partner have sex with another man (8.4 percent).

Next up, the researchers plan to map subgroups of sexual fantasies that often go together (for instance, those who reported submissive fantasies were also more likely to report domination fantasies, and both were associated with higher levels of overall sexual satisfaction). For now, they caution that “care should be taken before labeling (a sexual fantasy) as unusual, let alone deviant.”

It would be interesting to see the results of this study replicated in other areas — Quebec may or may not be representative of the rest of western society.

Update, 28 November: Maggie McNeill is not impressed by the study at all.

But there’s a bigger problem, which as it turns out I’ve written on before when the titillation du jour was the claim that fewer men were paying for sex:

… the General Social Survey … has one huge, massive flaw that was mentioned by my psychology professors way back in the Dark Ages of the 1980s, yet seems not to trouble those who rely upon it so heavily these days: it is conducted in person, face to face with the respondents. And that means that on sensitive topics carrying criminal penalties or heavy social stigma, the results are less than solid; negative opinions of its dependability on such matters range from “unreliable” to “useless”. The fact of the matter is that human beings want to look good to authority figures (like sociologists in white lab coats) even when they don’t know them from Adam, so they tend to deviate from strict veracity toward whatever answer they think the interviewer wants to hear…

So, what does this study say constitutes an “abnormal” fantasy?

“Clinically, we know what pathological sexual fantasies are: they involve non-consenting partners, they induce pain, or they are absolutely necessary in deriving satisfaction,” Christian Joyal, the lead author of the study, said…The researchers found that only two sexual fantasies were…rare: Sexual activities with a child or an animal…only nine sexual fantasies were considered unusual…[including] “golden showers,” cross-dressing, [and] sex with a prostitute…

Joyal’s claim that sadistic and rape fantasies are innately “pathological” is both insulting and totally wrong; we “know” no such thing. And did you think it was a coincidence that pedophilia and bestiality were the only two fantasies to fall into the “rare” category during a time when those are the two most vilified kinks in the catalog, kinks which will result in permanent consignment to pariah status if discovered? Guess again; as recently as the 1980s it was acceptable to at least talk about both of these, and neither is as rare as this “study” pretends. But Man is a social animal, and even if someone is absolutely certain of his anonymity (which in the post-Snowden era would be a much rarer thing than either of those fantasies), few are willing to risk the disapproval of a lab-coated authority figure even if he isn’t sitting directly in front of them. What this study shows is not how common these fantasies actually are, but rather how safe people feel admitting to them. And while that’s an interesting thing in itself, it isn’t what everyone from researchers to reporters to readers is pretending the study measured.

The “modern” House of Lords

The House of Lords is the upper chamber of Britain’s parliament. Canada’s (mostly useless) Senate is our equivalent legislative body, in that the members are not there through any kind of popular vote, and the general public view them — if they have any opinion about them at all — as an odd historical holdover that doesn’t really matter in today’s world. Recently, the Wall Street Journal talked about the House of Lords, and Tim Worstall wants to correct their misunderstandings about that august body:

The change to appointing Life Peers rather than hereditaries really came back in 1958, when it first became possible to appoint someone only for life, rather than appointing someone and finding out that their sons (only first son to first son of course, not all sons) to the nth generation also got membership of the House when the time came. Since then there have been very few hereditary peerages granted and those that have been have been special cases. Ex-Prime Ministers, if they desire, become Earls, ex-Speakers of the Commons Viscounts and after that, well, just some very few special people (such a William Whitelaw who became a Viscount, and everyone was assured that he only had daughters so it would not be inherited).

That is, Blair didn’t so much change the usual method of appointment, for that carried on in much the same way it had for the previous few decades. What he did do was remove the extant hereditaries (except for 92 of them, which is a whole other story). He also created a number of peerages in order to try and balance the party memberships in the Lords. But not excessively so perhaps. There’s a nice listing here of the numbers created under each PM and how many per year. Blair’s numbers are well above the historical average, yes, but rather below Cameron’s numbers per year (Cameron, of course, is trying to reverse the balance in favour of Labour that Blair engineered).

In other words it wasn’t so much “replacement” as the exclusion of the hereditaries leading to a much smaller House.

He also addresses the voiced concern that so many peers have (shock, horror!) business ties that might influence their voting:

Yes, many do indeed have contacts with firms in the economy. Quite possibly too many with not the right kind of firm. But then look back up to that first quote from the article. The Life Peers are drawn from, among other places, the captains of industry (and yes, senior trade union leaders get an equal look in, as do left leaning academics, Lord Glasman comes to mind there, as does my old professor, Lord Layard). If you appoint people from industry to the second house of the legislature then you’re going to have people with links to, and quite possibly paycheques from, industry in that second house of the legislature. George Simpson become Lord Simpson (one of them, there are several I think with that name, the distinction becoming “Simpson of Where”) while he was still ruining GEC. So, obviously, there was the Chairman of a defence related company sitting in the House of Lords. But he was appointed because he was head of GEC.

Similarly, one of the particular peers I did some work for had been instrumental in the creation and running of a very successful financial services firm. It was in part what he was made a Lord for. And while I’ve no idea what his financial relationship with his old firm is or was it wouldn’t surprise me if he was still drawing a paycheque or a pension from it.

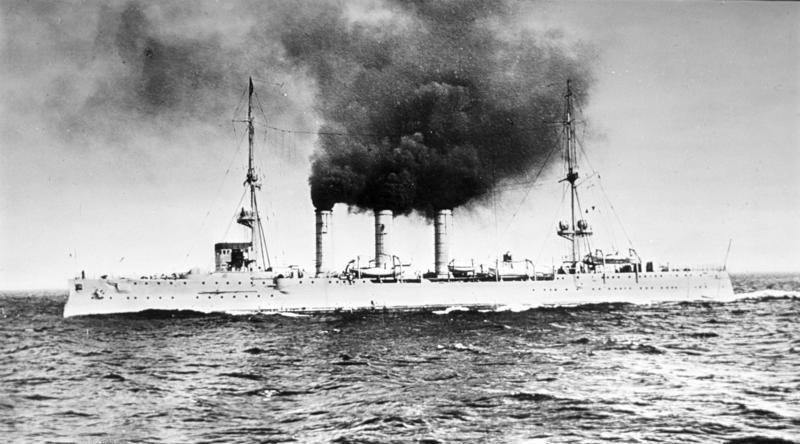

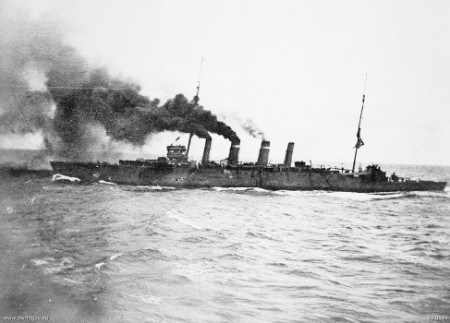

HMAS Sydney versus SMS Emden, 9 November 1914

Last Sunday was the 100th anniversary of the first major naval victory of the Royal Australian Navy, when Australian light cruiser HMAS Sydney fought against one of the Kaiser’s most effective commerce raiders, SMS Emden in the Indian Ocean:

November 9 is when the light cruiser HMAS Sydney met the light cruiser SMS Emden in action in the Indian Ocean, dispatching a surface raider that had taken a heavy toll on Allied merchant and naval shipping since the guns of August rang out. R. K. Lochner chronicled Emden’s exploits in the late 1970s, dubbing her “the last gentleman of war.” Lochner awarded the cruiser this title to acknowledge skipper Karl von Müller’s and his crew’s scrupulous fidelity to the laws of cruiser warfare. The Germans’ enemy paid homage to Emden’s gallantry as well. Two days after the engagement, for instance, the London Daily News saluted the “resourceful energy and chivalry” displayed by the raider’s crewmen throughout their voyage. That, of course, was an era when knightly conduct was in decline on the high seas, yielding to unrestricted submarine warfare. Striking without warning, as U-boats commonly did in the Atlantic, left mariners and passengers scant prospects of escaping an attack.

The battle, then, helped mark the passing of an age. Emden had remained behind at the onset of war, after the German East Asian Squadron quit Southeast Asia to return home. Hers was not destined to be a prolonged cruise. Cut off from logistical and maintenance support, Captain Müller had to forage for coal and stores. The cruiser coped with this hand-to-mouth existence — for a while — and in the process sank or captured twenty-five merchantmen, destroyed two Allied men-of-war at Penang, and bombarded the seaport of Madras, along the seacoast of British India. That’s quite a combat record. It’s especially noteworthy when compiled by seafarers who were unsure where they could refuel next — if anywhere at all — and were sure that equipment that suffered a major breakdown would never be repaired for want of spare parts and shipyard expertise.

The light cruiser HMAS Sydney steams towards Rabaul. The Australian Naval & Military Expeditionary Force (AN&MEF), which included HMAS Sydney, HMAS Australia, HMAS Encounter, HMAS Warrego, HMAS Yarra and HMAS Parramatta, seized control of German New Guinea on 11 September 1914 (via Wikipedia)

No ship can keep going for long without putting into port or tapping resources from nearby fuel or stores ships. Heck, U.S. Navy commanders — like their counterparts in other fleets, no doubt — get antsy when the fuel tanks drop to half-empty or hardware fails at sea, hampering performance or reducing redundancy in the propulsion plant or other critical machinery. And that’s in a navy accustomed to having logistics vessels steaming in company to top off the tanks, replenish stores, or transfer or manufacture spares when need be. Imagine being altogether alone in some faraway region — at risk of running out of some vital commodity or suffering battle damage and finding yourself dead in the water. Such loneliness and doubt were constant companions to Emden officers and men during the fall of 1914.It takes extraordinary pluck to seize the offensive amid such circumstances. And yet the Germans did. In November, nonetheless, Sydney found Emden in the Cocos (Keeling) Islands, where Müller had decided to attack a communications station that was aiding the hunt for his raider. Like so many naval actions, it was a chance encounter. The station got off a distress call, and Sydney — which happened to be in the vicinity while helping escort a convoy transporting Australian and New Zealand troops to Europe — responded to it. Emden gave a good account of herself, landing several punches before Sydney’s heavier main guns began to tell. Hopelessly outgunned, Müller ultimately ordered his vessel beached on North Keeling Island to save lives. Of the crew, 134 seamen fell while 69 were wounded and 157 were captured.

QotD: The difference between medicine and recreational drugs

I do occasional work for my hospital’s Addiction Medicine service, and a lot of our conversations go the same way.

My attending tells a patient trying to quit that she must take a certain pill that will decrease her drug cravings. He says it is mostly covered by insurance, but that there will be a copay of about one hundred dollars a week.

The patient freaks out. “A hundred dollars a week? There’s no way I can get that much money!”

My attending asks the patient how much she spends on heroin.

The patient gives a number like thirty or forty dollars a day, every day.

My attending notes that this comes out to $210 to $280 dollars a week, and suggests that she quit heroin, take the anti-addiction pill, and make a “profit” of $110.

At this point the patient always shoots my attending an incredibly dirty look. Like he’s cheating somehow. Just because she has $210 a week to spend on heroin doesn’t mean that after getting rid of that she’d have $210 to spend on medication. Sure, these fancy doctors think they’re so smart, what with their “mathematics” and their “subtracting numbers from other numbers”, but they’re not going to fool her.

At this point I accept this as a fact of life. Whatever my patients do to get money for drugs — and I don’t want to know — it’s not something they can do to get money to pay for medication, or rehab programs, or whatever else. I don’t even think it’s consciously about them caring less about medication than about drugs, I think that they would be literally unable to summon the motivation necessary to get that kind of cash if it were for anything less desperate than feeding an addiction.

Scott Alexander, “Apologia Pro Vita Sua”, Slate Star Codex, 2014-05-25.