Marc Wilson posted this to the Lois McMaster Bujold mailing list (off-topic, obviously):

Apparently the inventor of predictive text has died.

His funfair will be on Sundial.

Marc Wilson posted this to the Lois McMaster Bujold mailing list (off-topic, obviously):

Apparently the inventor of predictive text has died.

His funfair will be on Sundial.

Last month, Paul Richard Huard did a brief tribute to one of the iconic tanks of the Second World War, the M-4 Sherman. It was not a good tank, but it was good enough (if you ignore the survivability of the crews):

M4A1 Sherman tank at Canadian Forces Base Borden (via Wikipedia)

The M-4 Sherman was the workhorse medium tank of the U.S. Army and Marine Corps during World War II. It fought in every theater of operation — North Africa, the Pacific and Europe.

The Sherman was renown for its mechanical reliability, owing to its standardized parts and quality construction on the assembly line. It was roomy, easily repaired, easy to drive. It should have been the ideal tank.

But the Sherman was also a death trap.

Most tanks at the time ran on diesel, a safer and less flammable fuel than gasoline. The Sherman’s power plant was a 400-horsepower gas engine that, combined with the ammo on board, could transform the tank into a Hellish inferno after taking a hit.

All it took was a German adversary like the awe-inspiring Tiger tank with its 88-millimeter gun. One round could punch through the Sherman’s comparatively thin armor. If they were lucky, the tank’s five crew might have seconds to escape before they burned alive.

Hence, the Sherman’s grim nickname — Ronson, like the cigarette lighter, because “it lights up the first time, every time.”

Commonwealth units were allocated a proportion of Sherman tanks with the original 75mm or 76mm main gun replaced by a British 17-pounder anti-tank gun that gave Sherman Firefly tanks nearly the same punch as German Tiger tanks (and better than Panthers). There weren’t enough to go around, so they were parcelled out to allow a few Fireflies per troop or squadron. The 17-pounder gun also lacked a high explosive round for use against thin-skinned or unarmoured targets, so including one or two Fireflies among a group of conventionally armed Shermans was a good trade-off.

European Space Agency fails to harpoon a comet … successfully lands anyway:

In 1998, the Hollywood blockbuster Armageddon asked us to believe that it was possible to land a spacecraft on an asteroid hurtling towards Earth — too far-fetched, right? Not so. Today humanity just achieved the seemingly impossible.

Earlier this afternoon, scientists from the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Rosetta mission successfully landed the unmanned Philae lander module on comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko. The complexities of this mission are such that a short article cannot do justice to the men and women who made this mission a success, but here are a few of the mind-boggling highlights:

The Rosetta probe launched in March 2004 after years of careful planning. Since then, it has travelled 6.4 billion kilometres through the solar system to get into the orbit of the comet 67p, which itself is just four kilometres in diameter. Comet 67p is orbiting the Sun at speeds of up to 135,000 kilometres per hour and is currently about 500 million kilometres from Earth. After a period during which it successfully orbited comet 67p, the 100 kilogram Philae lander then separated from the Rosetta orbiter, descended slowly and landed safely.

At the time of writing, the latest reports from the ESA suggest there may have been some problems with the lander’s anchoring mechanism. The lander was designed to fire harpoons into the surface of the comet to ensure it stayed in place — this may not have worked. But to be fair, no one has tried harpooning a comet before, so a few glitches are understandable.

Update: BBC News has more on the unexpectedly bumpy landing and the risk that the lander may not be able to stay active very long due to battery limitations. Having landed in the shadow of a cliff, the batteries are not able to be recharged by the solar panels.

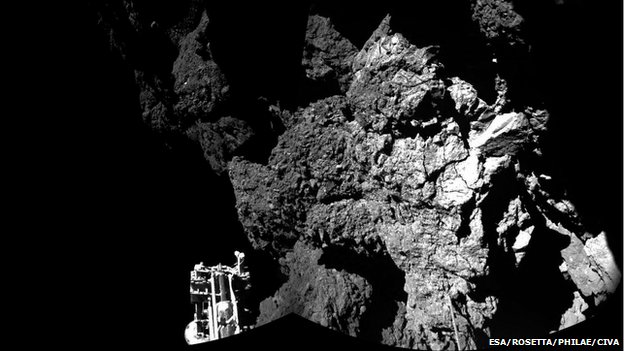

The craggy surface of the comet – looking over one of Philae’s feet

After two bounces, the first one about 1km back out into space, the lander settled in the shadow of a cliff, 1km from its target site.

It may be problematic to get enough sunlight to charge its batteries.

Launched in 2004, the European Space Agency (Esa) mission hopes to learn about the origins of our Solar System.

It has already sent back the first images ever taken on the surface of a comet.

Esa’s Rosetta satellite carried Philae on a 10-year, 6.4 billion-km (4bn-mile) journey to Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, which reached its climax on Wednesday.

After showing an image that indicates Philae’s location — on the far side of a large crater that was considered but rejected as a landing site — the head of the lander team Dr Stefan Ulamec said: “We could be somewhere in the rim of this crater, which could explain this bizarre… orientation that you have seen.”

Figuring out the orientation and location is a difficult task, he said.

“I can’t really give you much more than you interpret yourself from looking at these beautiful images.”

But the team is continuing to receive “great data” from several different instruments on board Philae.

Another problem with the lander — aside from not knowing exactly where it landed — is that one of the landing legs isn’t actually in contact with the surface:

Controllers re-established radio communication with the probe on cue on Thursday after a scheduled break, and began pulling of the new pictures.

These show the feet of the lander and the wider cometscape. One of the three feet is not in contact with the ground.

Philae is stable now, but there is still concern about the longer-term situation because the probe is not properly anchored — the harpoons that should have hooked it into the surface did not fire on contact. Neither did its feet screws get any purchase.

Lander project manager Stephan Ulamec told the BBC that he was very wary of now commanding the harpoons to fire, as this could throw Philae back off into space.

He also has worries about drilling into the comet to get samples for analysis because this too could affect the overall stability of the lander.

“We are still not anchored,” he said. “We are sitting with the weight of the lander somehow on the comet. We are pretty sure where we landed the first time, and then we made quite a leap. Some people say it is in the order of 1 km high.

“And then we had another small leap, and now we are sitting there, and transmitting, and everything else is something we have to start understanding and keep interpreting.”

Photo of the comet’s surface from about 40 metres as the lander made its initial descent.

Tim Harford — white, male Oxford grad and child of Oxbridge-educated parents — checks his privilege:

All these accidents of birth are important. But there’s a more important one: citizenship. Gillian, Simon and I are all British citizens. Financially speaking, this is a greater privilege than all the others combined.

Imagine lining up everyone in the world from the poorest to the richest, each standing beside a pile of money that represents his or her annual income. The world is a very unequal place: those in the top 1 per cent have vastly more than those in the bottom 1 per cent – you need about $35,000 after taxes to make that cut-off and be one of the 70 million richest people in the world. If that seems low, it’s $140,000 after taxes for a family of four – and it is also about 100 times more than the world’s poorest people have.

What determines who is at the richer end of that curve is, mostly, living in a rich country. Branko Milanovic, a visiting presidential professor at City University New York and author of The Haves and the Have-Nots, calculates that about 80 per cent of global inequality is the result of inequality between rich nations and poor nations. Only 20 per cent is the result of inequality between rich and poor within nations. […]

That might seem obvious but it’s often ignored in the conversations we have about inequality. And things used to be very different. In 1820, the UK had about three times the per capita income of countries such as China and India, and perhaps four times that of the poorest countries. The gap between rich countries and the rest has since grown. Today the US has about five times the per capita income of China, 10 times that of India and 50 times that of the poorest countries. (These gaps could be made to look even bigger by not adjusting for lower prices in China and India.) Being a citizen of the US, the EU or Japan is an extraordinary economic privilege, one of a dramatically different scale than in the 19th century.

After World War II, many left-wing European governments wanted to do something about unemployment. As I discuss extensively in my book, unemployment is about the worst thing that can happen to you in a modern democracy, short of death or dismemberment. So they passed laws making it very, very difficult to fire workers. In Italy, for example, a judge could reverse a layoff decision, not because you’d fired the worker unjustly, but because the judge didn’t think you needed to cut staff. Hurrah! Finally, workers were protected from the dark specter of unemployment!

Well, not quite. Workers were thrilled; employers were terrified. Now hiring a worker meant you were stuck with them unless they committed some absolutely flagrant offense — like, say, emptying the till and running out the door.

That’s a hell of a commitment to make to someone you barely know. So employers didn’t want to hire scary strangers; they wanted to hire close friends and family. Or, better yet, no one at all. Youth unemployment in many of these nations was staggering. The insiders had a great deal, but people without jobs found themselves consigned to a series of temporary, not-very-well-paid contracts. Or the dole.

The lesson is that when you make it harder to exit, you also make people reluctant to enter.

Megan McArdle, “Can Limiting Divorce Make Marriage Stronger?”, Bloomberg View, 2014-04-16

Powered by WordPress