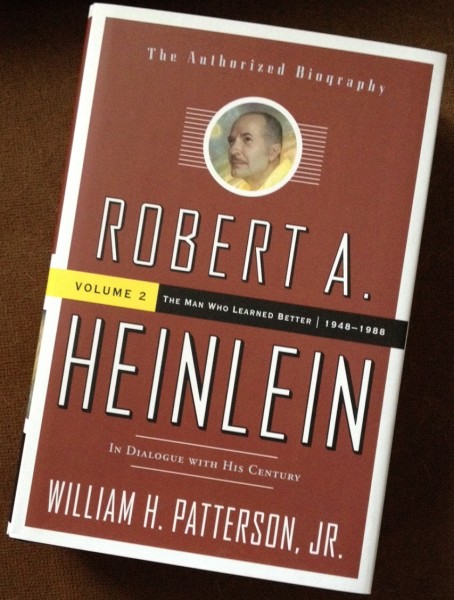

In the Washington Post, Michael Dirda reviews the second (and final) volume of William Patterson’s Robert A. Heinlein: In Dialogue With His Century.

In the Washington Post, Michael Dirda reviews the second (and final) volume of William Patterson’s Robert A. Heinlein: In Dialogue With His Century.

Robert Anson Heinlein (1907-1988) possessed an astonishing gift for fast-paced narrative, an exceptionally engaging voice and a willingness to boldly go where no writer had gone before. In “— All You Zombies—” a transgendered time traveler impregnates his younger self and thus becomes his own father and mother. The protagonist of Tunnel in the Sky is black, and the action contains hints of interracial sex, not the usual thing in a 1955 young adult book. While Starship Troopers (1959) championed the military virtues of service and sacrifice, Stranger in a Strange Land (1961) became a bible for the flower generation, blurring sex and religion and launching the vogue word “grok.”

Heinlein’s finest work in the short story was produced in the late 1930s and early ’40s, mainly for the legendary editor of Astounding, John W. Campbell. But by 1948, when this volume opens, “The Roads Must Roll,” “By His Bootstraps, “Gulf” and “Requiem” are behind him. The onetime pulp writer has broken into the Saturday Evening Post and Boy’s Life, married his third (and last) wife, Virginia, and settled in Colorado Springs, where he designs and builds a state-of-the-art automated house. Apart from his occasional involvement with Hollywood, as in scripting Destination Moon, he will devote the rest of his career mainly to novels.

[…]

Like his fascinating but long-winded first volume, the second half of Patterson’s biography is difficult to judge fairly. Packed with facts both trivial and significant, relying heavily on the possibly skewed memories of the author’s widow, and utterly reverent throughout, volume two emphasizes Heinlein the husband, traveler, independent businessman and political activist. Above all, the book celebrates the intense civilization of two that Heinlein and his wife created. There is almost nothing in the way of literary comment or criticism.

Though Heinlein can do no wrong in his biographer’s eyes, if you use yours to look in Patterson’s voluminous endnotes, you will occasionally find confirmation that the writer could be casually cruel as well as admirably generous, at once true to his beliefs and unpleasantly narrow-minded and inflexible about them. Today we would call Heinlein’s convictions libertarian, his personal philosophy grounded in absolute freedom, individual responsibility and an almost religiously inflected patriotism. Heinlein could thus be a confirmed nudist and member of several Sunshine Clubs as well as a grass-roots Barry Goldwater Republican.

For the record, I loved this volume even more than I loved the first one. But Dirda’s comments are fair: Patterson worked hard to present Heinlein in as positive a light as possible, so it’s not unreasonable to suspect that the great man’s character quirks could make him difficult and awkward to deal with at times (to be kind). In the last post, I talked about the adolescent Heinlein as being “probably a pretty toxic individual” and that aspect of his character can still be discerned in the recounting of his later years.