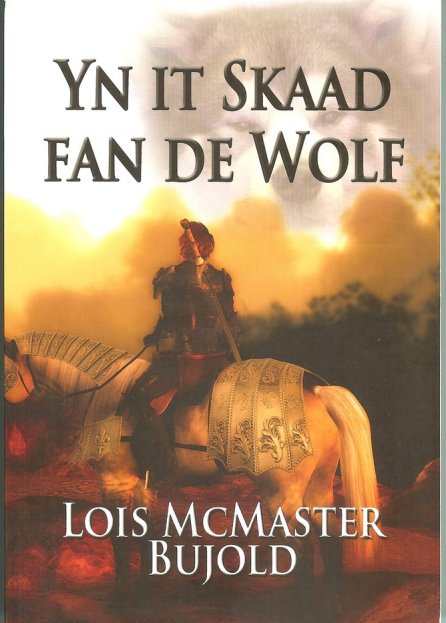

Lois McMaster Bujold posted an image to her Goodreads page, showing the cover of a new translation of The Hallowed Hunt into a language I didn’t think was still spoken:

She also posted a letter from the translator, which discusses some of the problems inherent in translating a fantasy novel into a language which only really became a written language quite recently:

Originally (we’re talking the early Middle Ages here), Frisian was the language closest related to English, but after more than a millennium of being heavily influenced by Dutch and German, this is no longer the case. Over the centuries, Dutch, German and the Low Saxon dialects of the eastern Netherlands and northern Germany have made such inroads into the original Frisian language area (once stretching all along the North Sea coast from what is now Belgium to Denmark), that it has crumbled into several small — or smallish — enclaves, which are still shrinking or at least remain under constant pressure. In the outside world, the term “Frisian” is generally used as if it were a monolithic language, but in fact there are three different Frisian languages, which are mutually quite incomprehensible and have been so for a long time.

• North Frisian is spoken in northern Germany, in an area along the North Sea coast and on the nearby islands directly south of the Danish border, by about 10,000 people.

• East Frisian was once spoken in the German coastal area adjacent to the Dutch border, but has gone extinct there, except for one small inland area, Saterland, which was originally surrounded by almost impassable peat bogs. Saterlandic, or Saterland Frisian, is still spoken today, by some 2,200 people.

• In the Dutch province of Friesland, Frisian is still spoken as a first language by about 350,000 people (out of a total provincial population of c.630,000). It has official status equal to Dutch, here, and some 110,000 inhabitants of the province speak it as a second language. There are a lot of Frisians who for the sake of (better) employment have moved away from Friesland, bringing the total number of native Frisian speakers in the Netherlands to c.450,000. From this point, I will refer to this language, my native tongue, as “Frisian”, which is the name we have for it (Frysk), but FYI, in English it is often called “West Frisian” (a somewhat confusing name, since in the Netherlands, that is what we call a Dutch dialect spoken in northern tip of the province of North Holland).

Today, Frisian is a minority language used by about 3% of the total Dutch population, and although a lot of things have changed for the better since the beginning of the 20th century, when the Frisian language movement first emerged, we still have to fight for our rights more often than not. To give you an impression of the situation we have to deal with, a 1994 survey showed that of the total number of inhabitants of Friesland (now c.630,000), 94% can understand Frisian, 74% can speak it, 65% can read it, and 17% can write it. (These are still the most recent numbers available; I’ve read that they’re in the process of doing a follow-up survey, but apparently the results aren’t in yet.)

On the subject of literary translations, it should be understood that this is a relatively new phenomenon for the Frisian language. The Bible was not published in Frisian until 1943, and Shakespeare’s entire oeuvre appeared in our language in eight big omnibus editions between 1955 and 1976 (although some plays, like Hamlet and A Midsummer Night’s Dream, had already been published separately in the twenties and thirties).

For any native Frisian readers who’d like to read this excellent book in your own language, you can buy the translation here.