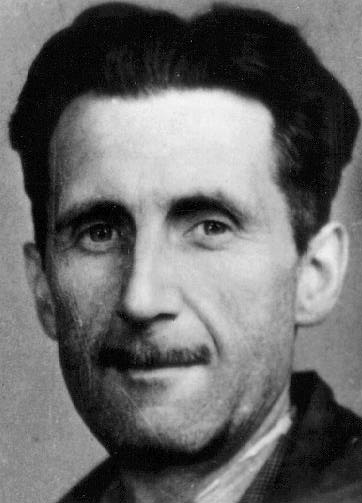

I’m not sure how you could characterize the great George Orwell as anything other than a socialist, unless you’ve never actually read any of his works:

One wonders whether the confusion stems from what [Krystal Ball] thinks she knows about Orwell’s politics? Contrary to the devout wishes of many conservatives, it remains an indisputable fact that George Orwell was a socialist. He was not “confused” about his politics. He was not a “capitalist in waiting.” He was not merely “living in another time.” He was a socialist, and he believed that, “wholeheartedly applied as a world system,” socialism could solve humanity’s problem. By contrast, he was wholly appalled by capitalism, which he described as a “racket” and which he believed led inexorably to “dole queues, the scramble for markets and war.” Abandoning a comfortable upbringing that had included an education at Eton and a stint as an imperial policeman in Burma, Orwell not only went out into the streets to discover how the other half lived but went so far as to risk his life for the cause, fighting for the Workers’ Party of Marxist Unification against Franco in the Spanish Civil War. (He was shot by a sniper, but survived.)When the Right seized upon 1984 (which his publisher quipped to his irritation might be worth “a cool million votes to the Conservative party”), Orwell reacted with controlled anger, explaining in a letter that was published in Life magazine that,

my novel Nineteen Eighty-Four is not intended as an attack on socialism, or on the British Labor party, but as a show-up of the perversions to which a centralized economy is liable, and which have already been partly realized in Communism and fascism.

So far, so clear.

And yet, admirably, he never lost his independence of mind, writing in the very next line of his explanation that,

I do not believe that the kind of society I describe necessarily will arrive, but I believe (allowing of course for the fact that the book is a satire) that something resembling it could arrive. I believe also that totalitarian ideas have taken root in the minds of intellectuals everywhere, and I have tried to draw these ideas out to their logical consequences.

This fear came to preoccupy him — and to the exclusion of almost everything else. “Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936,” he explained in Why I Write, “has been written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic Socialism, as I understand it.”

How he understood it was changing by the day. “Collectivism,” he warned in a 1944 book review, “leads to concentration camps, leader worship and war.” More important, perhaps, he admitted that this might always be so, suggesting that “there is no way out of this unless a planned economy can somehow be combined with the freedom of the intellect, which can only happen if the concept of right and wrong is restored to politics.” Like Wilde before him, he held that freedom of the intellect to be indispensable. The question: Could socialism accommodate it?

It is de rigeur these days to cast Orwell as being merely an anti-totalitarian socialist — a “democratic socialist,” if you will — and, in doing so to parrot the graduate student’s favorite assurance that, because Marxism has never been tried in any sufficiently developed country, its critics are condemning merely its “excesses.” Certainly, Orwell did not believe that the Soviet Union was in any meaningful way a “socialist” state: “Nothing,” he charged, “has contributed so much to the corruption of the original idea of socialism as the belief that Russia is a socialist country and that every act of its rulers must be excused, if not imitated.” But, dearly as he hoped it could be realized, he also never quite managed to convince himself that his form of socialism was possible either — let alone that it could coexist with the English liberties he so sharply championed. For Orwell, it was not simply a matter of distinguishing between the “good” and “bad” Left, but worrying whether the former would lead always to the latter — a concern that the British literary classes, which indulged Stalin’s horrors to an unimaginable degree, did little to assuage.