To the very young, to schoolteachers, as also to those who compile textbooks about constitutional history, politics, and current affairs, the world is a more or less rational place. They visualize the election of representatives, freely chosen from among those the people trust. They picture the process by which the wisest and best of these become ministers of state. They imagine how captains of industry, freely elected by shareholders, choose for managerial responsibility those who have proved their ability in a humbler role. Books exist in which assumptions such as these are boldly stated or tacitly implied. To those, on the other hand, with any experience of affairs, these assumptions are merely ludicrous. Solemn conclaves of the wise and good are mere figments of the teacher’s mind. It is salutary, therefore, if an occasional warning is uttered on this subject. Heaven forbid that students should cease to read books on the science of public or business administration — provided only that these works are classified as fiction. Placed between the novels of Rider Haggard and H.G. Wells, intermingled with volumes about ape men and space ships, these textbooks could harm no one. Placed elsewhere, among works of reference, they can do more damage than might at first sight seem possible.

C. Northcote Parkinson, “Preface”, Parkinson’s Law (and other studies in administration), 1957.

January 6, 2014

QotD: The illusion of a rational world

Police killed in line of duty – the good news and the not-so-good news

The good news is that in the United States, the number of police officers killed in the performance of their duties dropped to a level last seen in 1959. The bad news is that the number of people killed by the police didn’t drop:

The go-to phrase deployed by police officers, district attorneys and other law enforcement-related entities to justify the use of excessive force or firing dozens of bullets into a single suspect is “the officer(s) feared for his/her safety.” There is no doubt being a police officer can be dangerous. But is it as dangerous as this oft-deployed justification makes it appear?

The annual report from the nonprofit National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial Fund also found that deaths in the line of duty generally fell by 8 percent and were the fewest since 1959.

According to the report, 111 federal, state, local, tribal and territorial officers were killed in the line of duty nationwide this past year, compared to 121 in 2012.

Forty-six officers were killed in traffic related accidents, and 33 were killed by firearms. The number of firearms deaths fell 33 percent in 2013 and was the lowest since 1887.

This statistical evidence suggests being a cop is safer than its been since the days of Sheriff Andy Griffith. Back in 2007, the FBI put the number of justifiable homicides committed by officers in the line of duty at 391. That count only includes homicides that occurred during the commission of a felony. This total doesn’t include justifiable homicides committed by police officers against people not committing felonies and also doesn’t include homicides found to be not justifiable. But still, this severe undercount far outpaces the number of cops killed by civilians.

We should expect the number to always skew in favor of the police. After all, they are fighting crime and will run into dangerous criminals who may respond violently. But to continually claim that officers “fear for their safety” is to ignore the statistical evidence that says being a cop is the safest it’s been in years — and in more than a century when it comes to firearms-related deaths.

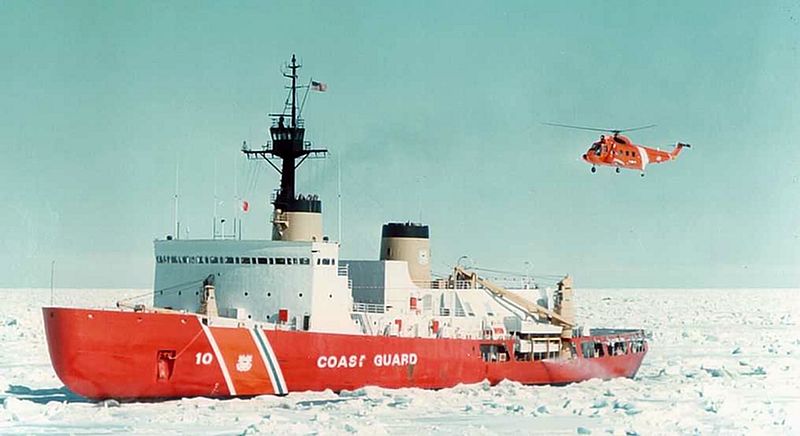

US icebreaker dispatched to assist Chinese icebreaker in Antarctic

The Australian is reporting that the US Coast Guard’s Polar Star is enroute to assist the Chinese icebreaker Xue Long and the chartered Russian ship Akademik Shokalskiy:

The Australian is reporting that the US Coast Guard’s Polar Star is enroute to assist the Chinese icebreaker Xue Long and the chartered Russian ship Akademik Shokalskiy:

The US Coast Guard’s Polar Star accepted a request from the Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA) to help the Russian ship Akademik Shokalskiy, which has been marooned since Christmas Eve.

It will also aid the Chinese icebreaker Xue Long, which was involved in a dramatic helicopter rescue of the Shokalskiy’s 52 passengers last Thursday before also becoming beset by ice.

AMSA confirmed the Polar Star, which was on its way from Seattle for an Antarctic mission, had diverted course and was on its way to help.

It will take about seven days for the icebreaker, with a crew of 140 people, to reach Commonwealth Bay after collecting supplies from Sydney today.

The AMSA spokeswoman said the Polar Star had greater capabilities than the Russian and Chinese vessels.

“It can break ice over six metres thick, while those vessels can break one-metre ice,” she told AAP on Sunday.

“The idea is to break them out, but they will make a decision once they arrive on scene on the best way to do this.” AMSA will be in regular contact with the US Coast Guard and the captain of the Polar Star during its journey to Antarctica.

Twenty-two crew remain on board the Shokalskiy, which sparked a rescue mission after a blizzard pushed sea ice around the ship and froze it in place on December 24.

Austria, the “laboratory of the Apocalypse”

Bethany Bell in Vienna writes about Austria just before the start of the war in 1914:

Across the road, a crowd had gathered outside a large, late 19th Century building. I walked over to have a look. It was the Embassy of what was then still Yugoslavia. An official had just pinned to the door two notices about the war that was, at that time, raging in Bosnia. Two men in front of me were talking about the siege of Sarajevo.

I shivered. History suddenly seemed very close.

A few months ago, a Viennese friend frowned as he stirred his coffee. We were sitting in Cafe Griensteidl, in the centre of town.

I’d just told him that, even after 15 years of living here, I’m still haunted by Vienna as it was just before the outbreak of World War One, before the defeat that led to the collapse of the rotting Austro-Hungarian Empire.

“But don’t lots of periods of history feel close in Vienna?” he asked. “You’ve got Mozart and the Baroque, you’ve got the 19th Century and the Ringstrasse, you’ve even got the Flak towers of the World War Two… Why not focus on them?”

I looked around at the cafe with its marble-topped tables and high white ceiling. Among the visitors and tourists, I recognised several senior Austrian civil servants, a couple of foreign diplomats and one of the country’s most distinguished historians.

“It’s partly the idea of cafe society,” I said lightly. “Just think who might have been sitting here back then!”

At the end of the 19th Century, Cafe Griensteidl was at the heart of Vienna’s dazzling intellectual life, patronised by people such as Arnold Schoenberg and Theodore Herzl. Sigmund Freud is thought to have preferred the nearby Cafe Landtmann.

“Ah, you have bought into the romance of fin-de-siecle Vienna!” he exclaimed. “You know that it was encouraged by some of Austria’s leaders after 1945. They wanted people to look back at a period of history they could be proud of — not like World War Two.”

He looked up at the Jugendstil mirror above our table.

“Even this cafe isn’t really genuine,” he said. “The original Griensteidl shut down in 1897 — this place was re-opened in the 1990s.”

“You know better than me that lots of traditions and places have survived,” I replied. “It’s not all fake — just look over there,” and I pointed through the window at the bank opposite. Built by the Modernist architect Adolf Loos, around 1910, the building had caused a scandal because of its severe lack of decoration.

“I think what haunts me is something a bit different,” I said.

“It’s the thought that this exquisite, civilised place didn’t seem to be able to stop its own collapse — and that it unleashed so many destructive ideas and people that tore Europe — and the 20th Century apart.”

The writer Karl Kraus had a phrase for it. In his obituary for Franz Ferdinand, he called Austria the laboratory of the Apocalypse.

My friend smiled wryly. “Ah, yes,” he said, “the Viennese, dancing towards destruction.”

Why patents were invented

In The Register, Tim Worstall explains why the notion of patents was introduced to the law and why we need to fix it now:

Having decided that the patent problem is an attempt to solve a public goods problem, as we did in part 1, let’s have a look at the specific ways that we put our oar into those perfect and competitive free markets.

It’s worth just noting that patents and copyright are not, absolutely not, the product of some fevered free market dreams. Rather, they’re an admission that “all markets all the time” does not solve all problems. That exactly why we create the patents.

Given that people find it very difficult to make money from the production of public goods, we think that we probably get too few of them. Innovation, the invention of new things for us to enjoy, is one of those public goods. It’s a hell of a lot easier to copy something you know can already be done than it is to come up with an invention yourself. So, if new inventions can be copied easily then we think that too few people will invent new things. We’re not OK with this idea. Thus we create a property right in that new invention. The inventor can now make money out of the invention and thus we get more new things.

And if it were only that simple, then of course we’d all be for patenting everything for ever. However it isn’t that simple. For not only do we want people to invent new things, we also want people to be able to adapt, extend, play with, improve those new things. Or apply them to areas the original inventor had no thought about. In the jargon, we want not just new inventions but also derivative ones. So we want to balance the ability of inventors to protect with the ability of others to do the deriving. And that’s probably what is actually wrong with our patent system today.

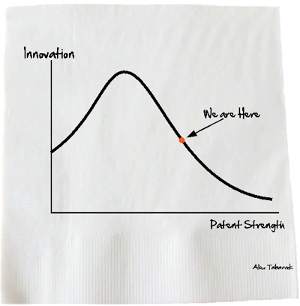

Have a look at Tabarrok’s curve:

Tabarrok’s curve (after Laffer’s curve), where economist Alex Tabarrok posits that, beyond a certain value, increased protection for intellectual property causes less innovation.

If we have no protection of originality, then we get too little innovation. But if we have too strong a protection, then we get too little of the derivative stuff. There’s a sweet spot and the argument is that we’re not at it at present and are thus missing out on some goodies as a result. Perhaps some tweaks to the system would help?

Boris Johnson – Germany started the war

In the Telegraph Boris Johnson is exasperated by recent comments that try to obscure or minimize the German role in starting the First World War:

It is a sad but undeniable fact that the First World War — in all its murderous horror — was overwhelmingly the result of German expansionism and aggression. That is a truism that has recently been restated by Max Hastings, in an excellent book, and that has been echoed by Michael Gove, the Education Secretary. I believe that analysis to be basically correct, and that it is all the more important, in this centenary year, that we remember it.

That fact is, alas, not one that the modern Labour Party believes it is polite to mention. According to the party’s education spokesman, Tristram Hunt, it is “crass” and “ugly” to say any such thing. It was “shocking”, he said in an article in yesterday’s Observer, that we continued to have this unacceptable focus on a “militaristic Germany bent on warmongering and imperial aggression”.

He went on — in a piece that deserves a Nobel prize for Tripe — to mount what appeared to be a kind of cock-eyed exculpation of the Kaiser and his generals. He pointed the finger, mystifyingly, at the Serbs. He blamed the Russians. He blamed the Turks for failing to keep the Ottoman empire together, and at one stage he suggested that we were too hard on the bellicose Junker class. He claimed that “modern scholarship” now believes that we have “underplayed the internal opposition to the Kaiser’s ideas within the German establishment” — as if that made things any better.

[…]

Hunt is guilty of talking total twaddle, but beneath his mushy-minded blether about “multiple histories” there is what he imagines is a kindly instinct. These wars were utterly horrific for the Germans as well as for everyone else, and the Germans today are very much our friends. He doesn’t want the 1914 commemorations to pander to xenophobia, or nationalism, or Kraut-bashing; and I am totally with him on that.

We all want to think of the Germans as they are today — a wonderful, peaceful, democratic country; one of our most important global friends and partners; a country with stunning technological attainments; a place of incomparable cultural richness and civilisation. What Hunt fails to understand — in his fastidious Lefty obfuscation of the truth — is that he is insulting the immense spiritual achievement of modern Germany.

The Germans are as they are today because they have been frank with themselves, and because over the past 60 years they have been agonisingly thorough in acknowledging the horror of what they did. They don’t try to brush it aside. They don’t blame the Serbs for the 1914-18 war. They don’t blame the Russians or the Turks. They know the price they paid for the militarism of the 20th century.