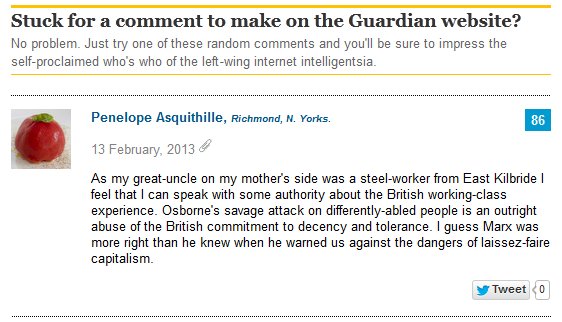

The Guardian-style comment generator:

February 13, 2013

Can we get versions of this for the Toronto Star and National Post?

Amity Shlaes on Coolidge

Ed Driscoll has an interview with author Amity Shlaes at PJMedia:

MR. DRISCOLL: How long after finishing The Forgotten Man did you start work on Coolidge, and how did you do your research?

MS. SHLAES: I think I started working on Coolidge while I was writing The Forgotten Man because I wrote one draft of Forgotten Man, this history in the 1930s. And then I thought well, this doesn’t work narratively because I didn’t describe what the change was from; where they started, what were their premises. Their premises were the premises of the ’20s and, you know, the ’20s premises were maybe smaller government is better, maybe still the pendulum of government action, reduce uncertainty in the policy environment so that a business can go forward. All these ideas were ideas from the ’20s, and whose ideas were they? Well, they were Calvin Coolidge’s and before Coolidge, Harding’s ideas. But mostly Coolidge’s, I think he’s the hero of the ’20s.

So I went back at the very last minute with Forgotten Man and put Coolidge in and he felt just right. I really liked him. And I thought well, we don’t — we don’t appreciate him much and what I learned in that short look for writing the new beginning to Forgotten Man made me want to go back and give him his own show.

MR. DRISCOLL: Coolidge is sadly remembered today by many people for only one quote and that’s “The business of America is business,” which is actually a bastardization of what Coolidge really said. Could you place that quote into context?

MS. SHLAES: Yes, that’s from a nice speech to newspaper people, actually. And he says the chief business of America is business, and he also says the chief ideal of Americans is idealism. So there’s a yoking together of two concepts, if you go back and read the whole speech, and it’s not fair to paint him as a only capitalism or capitalism to the exclusion of other areas. He’s not like Ayn Rand, for example, because he always tends to bring in the spiritual — other spheres in — and he doesn’t think only capitalism always prevails. He sees a balance. What he doesn’t like is when capitalism or business intrudes upon spiritual. And that’s very different from modern libertarianism.

So anyway it’s all there and that’s — he was extremely idealistic and extremely spiritual, some would say pious. Herbert Hoover called him a fundamentalist, and that was not a compliment coming from Herbert Hoover.

The imaginary trade-off between ecology and economics

Matt Ridley on the improvements in the environment in the western world:

Extrapolate global average GDP per capita into the future and it shows a rapid rise to the end of this century, when the average person on the planet would have an income at least twice as high as the typical American has today. If this were to happen, an economist would likely say that it’s a good thing, while an ecologist would likely say that it’s a bad thing because growth means using more resources. Therein lies a gap to be bridged between the two disciplines.

The environmental movement has always based its message on pessimism. Population growth was unstoppable; oil was running out; pesticides were causing a cancer epidemic; deserts were expanding; rainforests were shrinking; acid rain was killing trees; sperm counts were falling; and species extinction was rampant. For the green movement, generally, good news is no news. Many environmentalists are embarrassed even to admit that some trends are going in the right direction.

[. . .]

Why are environmental trends mainly positive? In short, the gains are due to “land sparing,” in which technological innovation allows humans to produce more from less land, leaving more land for forests and wildlife. The list of land sparing technologies is long: Tractors, unlike mules and horses, do not need to feed on hay. Advances in fertilizers and irrigation, as well as better storage, transport, and pest control, help boost yields. New genetic varieties of crops and livestock allow people to get more from less. Chickens now grow three times as fast in they did in the 1950s. The yield boosts from genetically modified crops is now saving from the plow an area equivalent to 24 percent of Brazil’s arable land.

What is really making a positive dent in the environmental arena is the unintended effects of technology rather than nature reserves or exhortations to love nature. Policy analyst Indur Goklany calculated that if we tried to support today’s population using the methods of the 1950s, we would need to farm 82 percent of all land, instead of the 38 percent we do now. The economist Julian Simon once pointed out that with cheap light, an urban, multi-story hydroponic warehouse the size of Delaware could feed the world, leaving the rest for wilderness.

It is not just food. In fiber and fuel too, we replace natural sources with synthetic, reducing the ecological footprint. Construction uses less and lighter materials. Even CO2 emissions enrich crop yields.

US Cyber Command’s recruiting headache

Strategy Page on the “who could possibly have seen this coming” problems that the new electronic warfare organization is having with staffing:

U.S. Cyber Command (USCYBERCOM) has been operational for two years now, and it is encountering some serious problems in recruiting people qualified to deal with the enemy (skilled hackers attacking American networks for whatever reason). People in the software and Internet security business have been telling Cyber Command leaders that they will have to change the way they recruit if they want to get qualified people. That means hiring hackers who lived on the dark side (criminal hacking) at one point or another. Such recruits would not pass the screening usually given to potential government employees who would be handling, and protecting, classified information and critical Internet systems. Few government officials are willing to bend the rules, mainly because no one wants to be responsible for some rogue hacker who got hired without the usual screening. It’s safer to go by the book and use that for your defense when the inadequate recruiting effort leads to a major Cyber War disaster.

Cyber Command is headquartered in Fort Meade (outside Washington, DC), most of the manpower, and capabilities, come from the Cyber War operations the military services have already established. Within Cyber Command there are some smaller organizations that coordinate Cyber War activities among the services, as well as with other branches of the government and commercial organizations that are involved in network security. At the moment Cyber Command wants to expand its core staff from 900 to 4,900 in the next five years. Twenty percent of those new people will be civilians, including a number of software specialists sufficiently skilled to quickly recognize skillful intrusions into American networks and quickly develop countermeasures. That kind of talent is not only expensive, but those who possess often have work histories that don’t pass the normal screening. These are the personnel Cyber Command is having a difficult time recruiting.

The big problems are not only recruiting hackers (technical personnel who can deal with the bad-guy hackers out there) but also managing them. The problem is one of culture, and economics. The military is a strict hierarchy that does not, at least in peacetime, reward creativity. Troops with good technical skills can make more money, and get hassled less, in a similar civilian job. The military is aware of these problems, but it is slow going trying to fix them.

Debunking the “1970s had a higher standard of living than today” meme

Don Boudreaux produces an anecdotal list of things that refute the inane notion that America’s standard of living peaked in the 1970s:

What follows here is drawn from memory. Perhaps my memory is grossly distorted, but my report of it here is an undistorted reflection of that memory. Here’s some of what I recall, of relevance to this discussion, from middle-class America of the 1970s; I offer the 25 items on this list in no particular order, except as they come to me.

(1) Automobiles broke down much more frequently than they break down today, hence, leaving motorists stranded, sometimes for hours, more often than is the case today.

(2) Automobiles rusted faster and more thoroughly than they do today.

(3) Someone in his or her early 70s was widely regarded as being quite old.

(4) “Old” people back then were much more likely to wear dentures than are “old” people today.

(5) Frozen foods in supermarkets were gawdawful by the standards of today – in terms both of quality and of selection.

[. . .]

(21) Coffee sucked. (It was almost all made from robusta beans.) And the selection of teas was pretty much limited to whatever Lipton sold.

(22) A diagnosis of cancer was far more frightening than it is today. Any person so diagnosed was regarded as being as good as dead.

(23) Going to college was much more unusual than it is today.

(24) Contact lenses were much more expensive than they are today. I purchased insurance (!) on my first pair of soft contact lenses (which I bought in 1980) in order to protect myself against the financial consequences of losing or damaging the one pair that I bought. (Such lenses were bought one pair at a time.)

(25) The idea of widespread use of personal computers seemed like science fiction. I very clearly recall overhearing, in the Spring of 1980, one of my economics professors, Wayne Shell (who also taught computer science), telling someone that he believed that, within a few years, many American households will have a computer. I thought at the time that Dr. Shell’s prediction was fancifully far-fetched.

I could go on, listing at least another 50 such recollections. But instead I’ll end this post here.

The Jazz Sweatshop (or the Harvard University of Jazz)

In the New York Review of Books, Christopher Carroll discusses the great Charles Mingus:

Mingus (1922-1979) would have turned ninety last year, and in celebration, Mosaic has released The Jazz Workshop Concerts: 1964-1965, a new box set with rare and previously unreleased performances by some of Mingus’s greatest ensembles. These concerts, recorded near the apex of Mingus’s career, are visceral and often unvarnished. At times, the music here can be forbidding — several tracks run beyond thirty minutes — and though it may not be as uniformly polished as some of his studio albums, at its best this set captures an element of shock and surprise that Mingus’s studio recordings sometimes don’t.

“Mingus music,” as he called it, was so complex and so much an extension of his own personality that it was largely played only by his own group, the Jazz Workshop. Turnover in the Workshop was high, partly because he couldn’t afford to pay his musicians very well, partly because the experience was so grueling (members called it the Jazz Sweatshop), and partly because so many of them, after sharpening their skills with Mingus, went on to lead their own bands (Gary Giddins once called it the Harvard University of Jazz).

Even with Mingus at the helm playing bass (and sometimes piano), Workshop performances often resembled practice sessions more than concerts. He did everything in his power to push his players beyond their limits: while a musician was soloing, he might double the tempo, cut it in half, or drop the accompaniment of the bass, drums, and piano entirely, all without warning. Often, players would buckle under the pressure and songs would grind to a halt, with Mingus screaming recriminations and heaping shame on everyone in sight. But sometimes his musicians would rise to the challenge, and it was the possibility of this transcendence that gave Jazz Workshop performances such an electrifying sense of expectation and adventure.