I have to admit that Johann Hari was pretty much just a British media personality I had a vague awareness of, but I hadn’t paid much attention to him (his Wikipedia sockpuppeting came to my attention in 2011, and I quoted from an article he wrote for the Los Angeles Times in 2019). As this post by Ben at Ben’s Comedy News outlines, I’d largely missed the rest of his fall and rise:

Nowadays, Johann Hari is known as a pop psychology expert. He does TED talks and writes books with simplistic messages like:

- your smartphone is ruining your attention span! (Stolen Focus)

- you should cure your depression by throwing away your medication and joining a book club! (Lost Connections)

- the war on drugs is bad! (Chasing the Scream)

His books get positive blurbs from distinguished thinkers, such as the comedian and twink admirer Stephen Fry, the listicle entrepreneur Arianna Huffington, the feminist and sex offender’s wife Hillary Clinton, the comedian and fake revolutionary Russell Brand, and the TV doctor Doctor Rangan Chatterjee.

But when you look at how actual experts assess his work, it’s not so positive. The neuroscientist Dean Burnett responded to an extract of Lost Connections in his Guardian column, under the title Is everything Johann Hari knows about depression wrong? Burnett points out that:

despite Hari’s prose suggesting he’s uncovered numerous revelations, pretty much everything he “reveals” is well known already

Hari, in pursuit of an anti-anti-depressant narrative, makes the claim that you can be diagnosed with depression and put on medication immediately after a traumatic event like losing a child, which Burnett (who teaches psychiatry) describes as:

at best a staggering exaggeration, at worst an active fabrication to support a narrative.

But this article isn’t about what Johann Hari has been doing recently. It’s about what Hari was up to before he reinvented himself as some kind of expert, back when he was a journalist who ended up being disgraced.

It’s about how Hari has somehow rounded allegations of serious fabrication down to a record of minor plagiarism. It’s about how in trying to attack his critics, he seems to have inadvertently revealed his penchant for little brother incest fantasies with a troubling racial dimension. It’s about how I tried to fix the record on Wikipedia, and ran into trouble as Wikipedia’s policies collided with the sorry state of British journalism.

Back in 2010, Johann Hari was a star newspaper columnist (if you’re a millennial that means he wrote hot takes that got lots of clicks; if you’re Gen Z, think of him as a viral TikTok star but with words on paper).

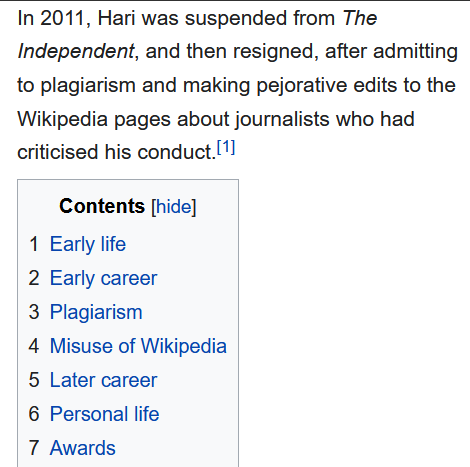

In 2011 he was disgraced and kicked out of the profession.

Now if you look at the articles that were written about his comeback, like this New Statesman piece or this Guardian piece you’d conclude that he was disgraced for two things:

plagiarism – specifically, taking quotes from text someone had written in a book or article, and pretending that the person had said it directly to him

abuse of Wikipedia – in particular, using a fake identity to edit the pages of professional rivals with false allegations

I followed the whole Hari affair pretty closely at the time (I didn’t like him because he had been a cheerleader for the Iraq War, so I enjoyed watching his career go down in flames).

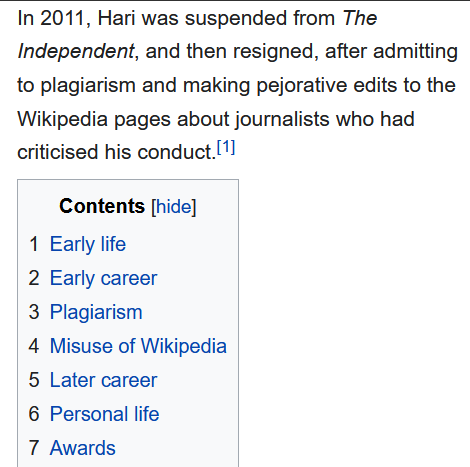

When his latest book came out a month ago, I looked at his Wikipedia entry. Wikipedia saves the history of all the different versions of each page, so here is a link to what I saw when I did that.

And here’s part of the summary and the table of contents:

The whole article struck me as weird because it didn’t mention two things I clearly remembered:

- Hari got in trouble, not just for minor plagiarism, but for allegedly making things up completely.

- Even more memorably, the fake identity he used to edit Wikipedia, “David Rose”, was also used to author an incest kink porn story with a hilarious title.

You can see why Hari (and whatever reputation management consultants he has working for him) would want to focus on the “plagiarism” angle. It’s not good to pass off a quote you got from someone’s book as something they told you directly, but it’s not as serious as completely inventing something. I suppose technically it’s plagiarism because you’re pretending you elicited the quote in an interview and you’re not citing the original book; but it’s a lot better than the typical case of plagiarism that involves passing off someone else’s work as your own. Hari’s defence is that he was “cutting corners” because he was under so much pressure due to his meteoric success at young age, etc. etc.