Take the curious phenomenon of the TED talk. TED – Technology, Entertainment, Design – is a global lecture circuit propagating “ideas worth spreading”. It is huge. Half a billion people have watched the 1,600 TED talks that are now online. Yet the talks are almost parochially American. Some are good but too many are blatant hard sells and quite a few are just daft. All of them lay claim to the future; this is another futurology land-grab, this time globalised and internet-enabled.

Benjamin Bratton, a professor of visual arts at the University of California, San Diego, has an astrophysicist friend who made a pitch to a potential donor of research funds. The pitch was excellent but he failed to get the money because, as the donor put it, “You know what, I’m gonna pass because I just don’t feel inspired … you should be more like Malcolm Gladwell.” Gladwellism – the hard sell of a big theme supported by dubious, incoherent but dramatically presented evidence – is the primary TED style. Is this, wondered Bratton, the basis on which the future should be planned? To its credit, TED had the good grace to let him give a virulently anti-TED talk to make his case. “I submit,” he told the assembled geeks, “that astrophysics run on the model of American Idol is a recipe for civilisational disaster.”

Bratton is not anti-futurology like me; rather, he is against simple-minded futurology. He thinks the TED style evades awkward complexities and evokes a future in which, somehow, everything will be changed by technology and yet the same. The geeks will still be living their laid-back California lifestyle because that will not be affected by the radical social and political implications of the very technology they plan to impose on societies and states. This is a naive, very local vision of heaven in which everybody drinks beer and plays baseball and the sun always shines.

The reality, as the revelations of the National Security Agency’s near-universal surveillance show, is that technology is just as likely to unleash hell as any other human enterprise. But the primary TED faith is that the future is good simply because it is the future; not being the present or the past is seen as an intrinsic virtue.

Bryan Appleyard, “Why futurologists are always wrong – and why we should be sceptical of techno-utopians: From predicting AI within 20 years to mass-starvation in the 1970s, those who foretell the future often come close to doomsday preachers”, New Statesman, 2014-04-10.

January 25, 2015

QotD: TED

January 20, 2015

QotD: Neuroscientific claims

One last futurological, land-grabbing fad of the moment remains to be dealt with: neuroscience. It is certainly true that scanners, nanoprobes and supercomputers seem to be offering us a way to invade human consciousness, the final frontier of the scientific enterprise. Unfortunately, those leading us across this frontier are dangerously unclear about the meaning of the word “scientific”.

Neuroscientists now routinely make claims that are far beyond their competence, often prefaced by the words “We have found that …” The two most common of these claims are that the conscious self is a illusion and there is no such thing as free will. “As a neuroscientist,” Professor Patrick Haggard of University College London has said, “you’ve got to be a determinist. There are physical laws, which the electrical and chemical events in the brain obey. Under identical circumstances, you couldn’t have done otherwise; there’s no ‘I’ which can say ‘I want to do otherwise’.”

The first of these claims is easily dismissed – if the self is an illusion, who is being deluded? The second has not been established scientifically – all the evidence on which the claim is made is either dubious or misinterpreted – nor could it be established, because none of the scientists seems to be fully aware of the complexities of definition involved. In any case, the self and free will are foundational elements of all our discourse and that includes science. Eliminate them from your life if you like but, by doing so, you place yourself outside human society. You will, if you are serious about this displacement, not be understood. You will, in short, be a zombie.

Bryan Appleyard, “Why futurologists are always wrong – and why we should be sceptical of techno-utopians: From predicting AI within 20 years to mass-starvation in the 1970s, those who foretell the future often come close to doomsday preachers”, New Statesman, 2014-04-10.

December 31, 2014

QotD: Dr. Johnson on the future

At another level, futurology implies that we are unhappy in the present. Perhaps this is because the constant, enervating downpour of gadgets and the devices of the marketeers tell us that something better lies just around the next corner and, in our weakness, we believe. Or perhaps it was ever thus. In 1752, Dr Johnson mused that our obsession with the future may be an inevitable adjunct of the human mind. Like our attachment to the past, it is an expression of our inborn inability to live in – and be grateful for – the present.

“It seems,” he wrote, “to be the fate of man to seek all his consolations in futurity. The time present is seldom able to fill desire or imagination with immediate enjoyment, and we are forced to supply its deficiencies by recollection or anticipation.”

Bryan Appleyard, “Why futurologists are always wrong – and why we should be sceptical of techno-utopians: From predicting AI within 20 years to mass-starvation in the 1970s, those who foretell the future often come close to doomsday preachers”, New Statesman, 2014-04-10.

September 4, 2014

The new absolutism

Brendan O’Neill on the rise of the absolutist mindset in science:

Who do you think said the following: “I always regret it when knowledge becomes controversial. It’s clearly a bad thing, for knowledge to be controversial.” A severe man of the cloth, perhaps, keen to erect a forcefield around his way of thinking? A censorious academic rankled when anyone criticises his work? Actually, it was Brian Cox, Britain’s best-known scientist and the BBC’s go-to guy for wide-eyed documentaries about space. Yes, terrifyingly, this nation’s most recognisable scientist thinks it is a bad thing when knowledge becomes the subject of controversy, which is the opposite of what every man of reason in modern times has said about knowledge.

Mr Cox made his comments in an interview with the Guardian. Discussing climate change, he accused “nonsensical sceptics” of playing politics with scientific fact. He helpfully pointed out what us non-scientific plebs are permitted to say about climate change. “You’re allowed to say, well I think we should do nothing. But what you’re not allowed to do is to claim there’s a better estimate of the way that the climate will change, other than the one that comes out of the computer models.” Well, we are allowed to say that, even if we’re completely wrong, because of a little thing called freedom of speech. Mr Cox admits that his decree about what people are allowed to say on climate change springs from an absolutist position. “The scientific view at the time is the best, there’s nothing you can do that’s better than that. So there’s an absolutism. It’s absolutely the best advice.”

It’s genuinely concerning to hear a scientist — who is meant to keep himself always open to the process of falsifiabilty — describe his position as absolutist, a word more commonly associated with intolerant religious leaders. But then comes Mr Cox’s real blow against full-on debate. “It’s clearly a bad thing, for knowledge to be controversial”, he says. This is shocking, and the opposite of the truth. For pretty much the entire Enlightenment, the reasoned believed that actually it was good — essential, in fact — for knowledge to be treated as controversial and open to the most stinging questioning.

July 3, 2014

Skeptical reading should be the rule for health news

We’ve all seen many examples of health news stories where the headline promised much more than the article delivered: this is why stories have headlines in the first place — to get you to read the rest of the article. This sometimes means the headline writer (except on blogs, the person writing the headline isn’t the person who wrote the story), knowing less of what went into writing the story, grabs a few key statements to come up with an appealing (or appalling) headline.

This is especially true with science and health reporting, where the writer may not be as fully informed on the subject and the headline writer almost certainly doesn’t have a scientific background. The correct way to read any kind of health report in the mainstream media is to read skeptically — and knowing a few things about how scientific research is (or should be) conducted will help you to determine whether a reported finding is worth paying attention to:

Does the article support its claims with scientific research?

Your first concern should be the research behind the news article. If an article touts a treatment or some aspect of your lifestyle that is supposed to prevent or cause a disease, but doesn’t give any information about the scientific research behind it, then treat it with a lot of caution. The same applies to research that has yet to be published.

Is the article based on a conference abstract?

Another area for caution is if the news article is based on a conference abstract. Research presented at conferences is often at a preliminary stage and usually hasn’t been scrutinised by experts in the field. Also, conference abstracts rarely provide full details about methods, making it difficult to judge how well the research was conducted. For these reasons, articles based on conference abstracts should be no cause for alarm. Don’t panic or rush off to your GP.

Was the research in humans?

Quite often, the ‘miracle cure’ in the headline turns out to have only been tested on cells in the laboratory or on animals. These stories are regularly accompanied by pictures of humans, which creates the illusion that the miracle cure came from human studies. Studies in cells and animals are crucial first steps and should not be undervalued. However, many drugs that show promising results in cells in laboratories don’t work in animals, and many drugs that show promising results in animals don’t work in humans. If you read a headline about a drug or food ‘curing’ rats, there is a chance it might cure humans in the future, but unfortunately a larger chance that it won’t. So there is no need to start eating large amounts of the ‘wonder food’ featured in the article.

How many people did the research study include?

In general, the larger a study the more you can trust its results. Small studies may miss important differences because they lack statistical “power”, and are also more susceptible to finding things (including things that are wrong) purely by chance.

[…]

Did the study have a control group?

There are many different types of studies appropriate for answering different types of questions. If the question being asked is about whether a treatment or exposure has an effect or not, then the study needs to have a control group. A control group allows the researchers to compare what happens to people who have the treatment/exposure with what happens to people who don’t. If the study doesn’t have a control group, then it’s difficult to attribute results to the treatment or exposure with any level of certainty.

Also, it’s important that the control group is as similar to the treated/exposed group as possible. The best way to achieve this is to randomly assign some people to be in the treated/exposed group and some people to be in the control group. This is what happens in a randomised controlled trial (RCT) and is why RCTs are considered the ‘gold standard’ for testing the effects of treatments and exposures. So when reading about a drug, food or treatment that is supposed to have an effect, you want to look for evidence of a control group and, ideally, evidence that the study was an RCT. Without either, retain some healthy scepticism.

June 2, 2014

Six “red flags” to identify medical quackery

Dr. Amy Tuteur shares six things to watch for in health or medical reporting, as they usually indicate quackery:

Americans tend to be pretty savvy about advertising. Put a box around claims, annotate them with the words “paid advertisement” or “sponsored content” and most people approach those claims warily. Unfortunately, the same people who are dubious about advertising claims are remarkably gullible when it comes to quackery.

That’s the bad news. The good news is that it is surprisingly easy to tell quackery apart from real medical information. Quack claims are typically decorated with red flags … if you know what to look for. What follows is a list of some of those red flags.

1. The secret knowledge flag: When someone implies they are sharing secret medical knowledge with you, run in the opposite direction. There is no such thing as secret medical knowledge. In an age where there are literally thousands of competing medical journals, tremendous pressure on researchers to publish papers, and instantaneous dissemination of results on the Internet, nothing about medicine could possibly be secret.

2. The giant conspiracy flag: In the entire history of modern medicine, there has NEVER been a conspiracy to hide lifesaving information among professionals. Sure, an individual company may hide information in order to get a jump on competitors, or to deny harmful effects of their products, but there can never be a large conspiracy because every aspect of the healthcare industry is filled with competitors. Vast conspiracies, encompassing doctors, scientists and public health officials exist only in the minds of quacks.

[…]

4. The toxin flag: I’ve written before that toxins are the new evil humors. Toxins serve the same explanatory purpose as evil humours did in the Middle Ages. They are invisible, but all around us. They constantly threaten people, often people who unaware of their very existence. They are no longer viewed as evil in themselves, but it is axiomatic that they have be released into our environment by “evil” corporations. There’s just one problem. “Toxins” are a figment of the imagination, in the exact same way that evil humours and miasmas were figments of the imagination.

June 1, 2014

Healthy eating … the Woody Allen moment approaches

The “prophecy”:

And in The Economist this week:

Ms Teicholz describes the early academics who demonised fat and those who have kept up the crusade. Top among them was Ancel Keys, a professor at the University of Minnesota, whose work landed him on the cover of Time magazine in 1961. He provided an answer to why middle-aged men were dropping dead from heart attacks, as well as a solution: eat less fat. Work by Keys and others propelled the American government’s first set of dietary guidelines, in 1980. Cut back on red meat, whole milk and other sources of saturated fat. The few sceptics of this theory were, for decades, marginalised.

But the vilification of fat, argues Ms Teicholz, does not stand up to closer examination. She pokes holes in famous pieces of research — the Framingham heart study, the Seven Countries study, the Los Angeles Veterans Trial, to name a few — describing methodological problems or overlooked results, until the foundations of this nutritional advice look increasingly shaky.

The opinions of academics and governments, as presented, led to real change. Food companies were happy to replace animal fats with less expensive vegetable oils. They have now begun abolishing trans fats from their food products and replacing them with polyunsaturated vegetable oils that, when heated, may be as harmful. Advice for keeping to a low-fat diet also played directly into food companies’ sweet spot of biscuits, cereals and confectionery; when people eat less fat, they are hungry for something else. Indeed, as recently as 1995 the AHA itself recommended snacks of “low-fat cookies, low-fat crackers…hard candy, gum drops, sugar, syrup, honey” and other carbohydrate-laden foods. Americans consumed nearly 25% more carbohydrates in 2000 than they had in 1971.

It would be ironic indeed if the modern obesity crisis was actually caused by government dietary recommendations intended to improve public health (and fatten the bottom lines of big agribusiness campaign donors).

May 23, 2014

QotD: Futurologists

Futurologists are almost always wrong. Indeed, Clive James invented a word – “Hermie” – to denote an inaccurate prediction by a futurologist. This was an ironic tribute to the cold war strategist and, in later life, pop futurologist Herman Kahn. It was slightly unfair, because Kahn made so many fairly obvious predictions – mobile phones and the like – that it was inevitable quite a few would be right.

Even poppier was Alvin Toffler, with his 1970 book Future Shock, which suggested that the pace of technological change would cause psychological breakdown and social paralysis, not an obvious feature of the Facebook generation. Most inaccurate of all was Paul R Ehrlich who, in The Population Bomb, predicted that hundreds of millions would die of starvation in the 1970s. Hunger, in fact, has since declined quite rapidly.

Perhaps the most significant inaccuracy concerned artificial intelligence (AI). In 1956 the polymath Herbert Simon predicted that “machines will be capable, within 20 years, of doing any work a man can do” and in 1967 the cognitive scientist Marvin Minsky announced that “within a generation … the problem of creating ‘artificial intelligence’ will substantially be solved”. Yet, in spite of all the hype and the dizzying increases in the power and speed of computers, we are nowhere near creating a thinking machine.

Bryan Appleyard, “Why futurologists are always wrong – and why we should be sceptical of techno-utopians: From predicting AI within 20 years to mass-starvation in the 1970s, those who foretell the future often come close to doomsday preachers”, New Statesman, 2014-04-10.

April 25, 2014

Is it science or “science”? A cheat sheet

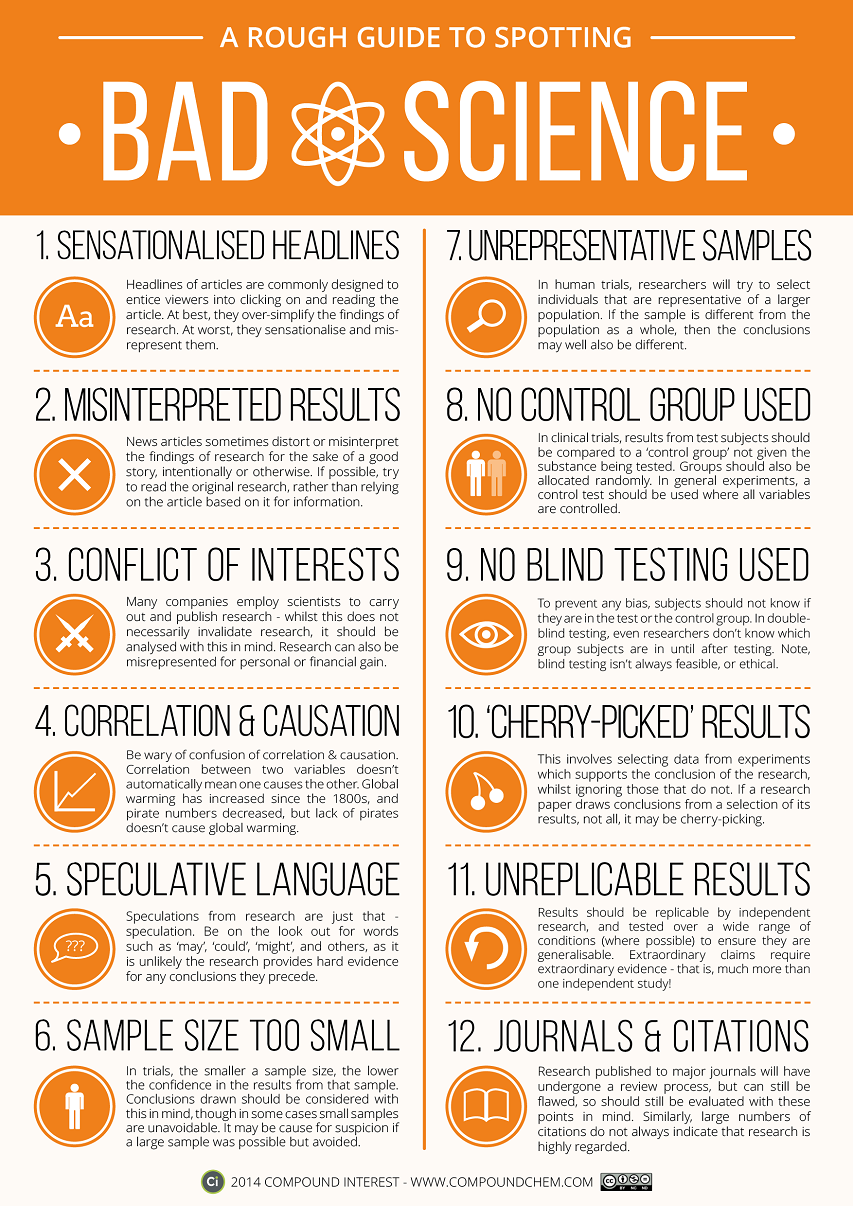

At Lifehacker, Alan Henry links to this useful infographic:

Science is amazing, but science reporting can be confusing at times and misleading at worst. The folks at Compound Interest put together this reference graphic that will help you pick out good articles from bad ones, and help you qualify the impact of the study you’re reading

One of the best and worst things about having a scientific background is being able to see when a science story is poorly reported, or a preliminary study published as if it were otherwise. One of the worst things about writing about science worrying you’ll fall into the same trap. It’s a constant struggle, because there are interesting takeaways even from preliminary studies and small sample sizes, but it’s important to qualify them as such so you don’t misrepresent the research. With this guide, you’ll be able to see when a study’s results are interesting food for thought that’s still developing, versus a relatively solid position that has consensus behind it.

April 16, 2014

Thought experiment – in media reports, replace “scientist” with “some guy”

Frank Fleming makes an interesting point:

Our society holds scientists in high esteem. When scientists say something — whether it’s about the composition of matter, the beginning of the universe, or who would win a fight between a giant gorilla and a T. Rex — we all sit up and listen. And it doesn’t matter if they say something that sounds completely ridiculous; as long as a statement is preceded with “scientists say,” we assume it is truth.

There’s just one problem with that: There are no such things as scientists.

Okay, you’re probably saying, “What? Scientists are real! I’ve seen them before! There’s even a famous, blurry photo of a man in a lab coat walking through the woods.” Well, yes, there are people known as scientists and who call themselves such, but the word is pretty much meaningless.

[…]

Which brings us back to our problem. So much of science these days seems to be built on faith — faith being something that doesn’t have anything to do with science. Yet everyone apparently has faith that all these scientists we hear about follow good methods and are smart and logical and unbiased — when we can’t actually know any of that. So often news articles contain phrases such as, “scientists say,” “scientists have proven,” “scientists agree” — and people treat those phrases like they mean something by themselves, when they don’t mean anything at all. It’s like if you wanted music for your wedding, and someone came up to you and said, “I know a guy. He’s a musician.”

“What instrument does he play?”

“He’s a musician.”

“Is he any good?”

“He’s a musician.”

You see, when other occupations are vaguely described, we know to ask questions, but because we have blind faith in science, such reason is lost when we hear the term “scientist.” Which is why I’m arguing that for the sake of better scientific understanding, we should get rid of the word and simply replace it with “some guy.”

It’s not exactly a new phenomenon: Robert Heinlein put these words in the mouth of Lazarus Long, “Most ‘scientists’ are bottle washers and button sorters.” It was true then, and if anything it’s even more true now as we have so many more people working in scientific fields.

April 10, 2014

QotD: Confirmation bias for thee but not for me

The last few days have provided both a good laugh and some food for thought on the important question of confirmation bias — people’s tendency to favor information that confirms their pre-existing views and ignore information that contradicts those views. It’s a subject well worth some reflection.

The laugh came from a familiar source. Without (it seems) a hint of irony, Paul Krugman argued on Monday that everyone is subject to confirmation bias except for people who agree with him. He was responding to this essay Ezra Klein wrote for his newly launched site, Vox.com, which took up the question of confirmation bias and the challenges it poses to democratic politics. Krugman acknowledged the research that Klein cites but then insisted that his own experience suggests it is actually mostly people he disagrees with who tend to ignore evidence and research that contradicts what they want to believe, while people who share his own views are more open-minded, skeptical, and evidence driven. I don’t know when I’ve seen a neater real-world example of an argument that disproves itself. Good times.

Yuval Levin, “Confirmation Bias and Its Limits”, National Review, 2014-04-09

March 22, 2014

The “narrative”

Wilfred McClay noticed the increasing use of the term “narrative” over the last few years:

We have this term now in circulation: “the narrative.” It is one of those somewhat pretentious academic terms that has wormed its way into common speech, like “gender” or “significant other,” bringing hidden freight along with it. Everywhere you look, you find it being used, and by all kinds of people. Elite journalists, who are likely to be products of university life rather than years of shoe-leather reporting, are perhaps the most likely to employ it, as a way of indicating their intellectual sophistication. But conservative populists like Rush Limbaugh and Sean Hannity are just as likely to use it too. Why is that so? What does this development mean?

I think the answer is clear. The ever more common use of “narrative” signifies the widespread and growing skepticism about any and all of the general accounts of events that have been, and are being, provided to us. We are living in an era of pervasive genteel disbelief — nothing so robust as relativism, but instead something more like a sustained “whatever” — and the word “narrative” provides a way of talking neutrally about such accounts while distancing ourselves from a consideration of their truth. Narratives are understood to be “constructed,” and it is assumed that their construction involves conscious or unconscious elements of selectivity — acts of suppression, inflation, and substitution, all meant to fashion the sequencing and coloration of events into an instrument that conveys what the narrator wants us to see and believe.

These days, even your garage mechanic is likely to speak of the White House narrative, the mainstream-media narrative, and indicate an awareness that political leaders try to influence the interpretation of events at a given time, or seek to “change the narrative” when things are not turning out so well for them and there is a strongly felt need to change the subject. The language of “narrative” has become a common way of talking about such things.

One can regret the corrosive side effects of such skepticism, but there are good reasons for it. Halfway through the first quarter of the 21st century, we find ourselves saddled with accounts of our nation’s past, and of the trajectory of American history, that are demonstrably suspect, and disabling in their effects. There is a view of America as an exceptionally guilty nation, the product of a poisonous mixture of territorial rapacity emboldened by racism, violence, and chauvinistic religious conviction, an exploiter of natural resources and despoiler of natural beauty and order such as the planet has never seen. Coexisting with that dire view is a similarly exaggerated Whiggish progressivism, in which all of history is seen as a struggle toward the greater and greater liberation of the individual, and the greater and greater integration of all governance in larger and larger units, administered by cadres of experts actuated by the public interest and by a highly developed sense of justice. The arc of history bends toward the latter view, although its progress is impeded by the malign effects of the former one.

January 16, 2014

H.L. Mencken’s Bathtub hoax

Wendy McElroy remembers one of the greatest publishing hoaxes of the 20th century:

On December 28, 1917, Mencken published the article “A Neglected Anniversary” in the New York Evening Mail. He announced that America had forgotten to celebrate the seventy-fifth anniversary of the modern bathtub, which had been invented on December 20, 1842 in Cincinnati, Ohio. “Not a plumber fired a salute or hung out a flag. Not a governor proclaimed a day of prayer,” Mencken lamented. He proceeded to offer an informal history of the US bathtub, with political context. For example, President Millard Fillmore had installed the first one in the White House in 1851. This had been a brave act since the health risks of using a bathtub were highly controversial within the medical establishment. Indeed, Mencken observed, “Boston early in 1845 made bathing unlawful except upon medical advice, but the ordinance was never enforced and in 1862, it was repealed.”

The actual political context was somewhat different. America had entered World War I several months before. The media was now rabidly anti-German and pro-war. Mencken was of German descent and anti-war. Suddenly, he was unable to publish in his usual venues or on his usual subjects. Thus, Mencken – a political animal to the core – turned to non-political writing in order to publish anything: A Book of Prefaces on literary criticism (1917); In Defense of Women on the position of women in society (1918); and The American Language (1918). But he was effectively shut out of the most important event in the world, the one about which he cared most.

Mencken did not just get mad; he got even. “A Neglected Anniversary” was a satire destined to become a classic of this genre. In his article, Mencken spoke in a tone of mock-reason, which was supported by bogus citations and manufactured statistics. His history of the bathtub was an utter hoax set within the framework of real history. The modern bathtub had not been invented in Cincinnati. Fillmore had not introduced the first one into the White House. The anti-bathtub laws cited were, to use one of Mencken’s favorite words, “buncombe.”

[…]

Mencken remained silent about the hoax until an article titled “Melancholy Reflections” was published in the Chicago Tribune on May 23, 1926, eight years later. It was Mencken’s confession and an appeal to the American public for reason. His hoax had gone bad. “A Neglected Anniversary” had been reprinted hundreds of times. Mencken had received letters of corroboration from some readers and requests for more details from others. His history of the bathtub had been cited by other writers and was starting to find its way into reference works. As Mencken noted in “Melancholy Reflections,” his ‘facts’ “began to be used by chiropractors and other such quacks as evidence of the stupidity of medical men. They began to be cited by medical men as proof of the progress of public hygiene.” And, because Fillmore’s presidency had been so uneventful, on the date of his birthday calendars often included the only interesting tidbit they could find: Fillmore had introduced the bathtub into the White House. (Even the later scholarly disclosure that Andrew Jackson had a bathtub installed there in 1834 did not diminish America’s conviction that Fillmore was responsible.)

Upon confessing, Mencken wondered if the truth would renew the cry for his deportation. The actual response: Many believed his confession was the hoax.

August 1, 2012

Climate science as religion, complete with confession and absolution

In sp!ked, Rob Lyons explains why the “climate skeptic” credentials of Professor Richard A Muller don’t quite add up, and helpfully provides a guide to the larger skeptic community:

There has been much rejoicing among eco-commentators. Leo Hickman in the Guardian declared: ‘So, that’s it then. The climate wars are over. Climate sceptics have accepted the main tenets of climate science — that the world is warming and that humans are largely to blame — and we can all now get on to debating the real issue at hand: what, if anything, do we do about it?’ However, Hickman had to add ‘If only’. Apparently, while Muller is the right kind of sceptic, some pesky critics just won’t accept the ‘facts’. ‘The power of his findings lay in the journey he has undertaken to arrive at his conclusions’, suggests Hickman, but clearly some people don’t get it.

It sounds like a powerful argument: someone who has publicly taken a position for a few years, before putting up his hands and effectively saying: ‘You know what? I was wrong, and my fellow travellers were wrong, and we should just fall into line with the mainstream view.’ The conversion analogy is a good one. Here, instead of the unbeliever falling at the preacher’s feet and accepting Jesus into their lives, no longer able to resist the power of the Lord, we have the sceptic allowing the IPCC to drive out the devil of climate-change denial from within his soul.

Except, like many a modern faith healer’s performance, there’s something dodgy about this widespread interpretation. For starters, Muller was hardly what you would call a climate-change sceptic. By and large, he has been very accepting of the IPCC’s view of the problem of climate change. His claim to being a sceptic seems to relate to his acceptance that the famous ‘hockey stick’ graph, which was the centrepiece of the IPCC’s 2001 report and suggested that current temperatures are unprecedented, was simply the product of some sloppy science.

In spite of the media attempts to blacken the reputations of everyone who fails to fall into line with the IPCC’s orthodoxy, there are many different strains of disagreement with the official line:

But to a certain extent, this is all a false debate. There is no either/or. The leading climate sceptics all accept that humans have had some influence on the world’s climate. The argument is about how much human influence there is and what should be done about it.

Alarmists would argue that greenhouse-gas emissions are threatening to cook the planet and ultimately threaten humanity’s survival. At the very least, they see devastating destruction arising from global warming. For them, the only answer is the rapid decarbonisation of the world economy. Since the world is currently reliant on carbon-based fuels, this could mean an end to the drive for economic growth and the reorganisation of the economy and global politics. Anyone who disagrees is a ‘denier’. Some alarmists seriously suggest that debate should end now and anyone who continues to question the ‘consensus’ should be punished.

A few individuals aside, most climate sceptics think the world is moderately warmer than before, that humans have had some effect, but that most of the variation is natural and not particularly worrisome. Another band of sceptics — those who might be called ‘policy sceptics’, like Bjorn Lomborg and Roger Pielke Jr — broadly accept the IPCC’s view of temperature change and its causes. However, they think that the answer lies in devoting resources to technological development in the short term rather than a costly and probably futile attempt to decarbonise the world overnight. But even such policy disagreement is too much for the alarmists, who regularly pillory Lomborg in particular, yet it gets dressed up as ‘scientific fact’.

May 4, 2012

A skeptical review of Get Real

Tim Black reviews the new book Get Real: How to Tell it Like it is in a World of Illusions by Eliane Glaser, calling it “enjoyably hyperactive”, but also pointing out some quite glaring flaws:

Politicians marshalling an army of PR consultants to appear authentic. Multinational companies selling products with folksy, homespun brands. Public inquiries that have nothing to do with the public. The paradoxes proliferate in journalist and academic Eliane Glaser’s enjoyably hyperactive new book, Get Real: How to Tell it Like it is in a World of Illusions. Her ambition is overarching: she wants to show us the way to the truth of the matter. She wants to cut through the crap. She wants us to follow the royal road of social critique. In short, she wants us to see things for what they are. (A bit rubbish, as it turns out.)

[. . .]

Glaser is even better when it comes to ‘scientism’. Awe-struck deference is everywhere, she argues, from Brian Cox’s television series Wonders of the Universe to the World of Wonders science museum in California. ‘Scientific wonder carries with it a sense of humility, which is ostensibly about meekness in the face of extraordinary facts’, she writes. ‘But it blurs into deference towards scientists, with their privileged access to those facts.’ Indeed, anything that Stephen Hawking says, be it about the existence of God or the plight of the planet, is treated as if it comes straight from the oracle’s mouth. ‘In modern culture, scientism is the new religion. God knows what happened to scepticism.’

This conflation of fact with value, this belief that science, having seemingly supplanted moral and political reasoning, can tell us what to do, is highly damaging, Glaser argues. Political decisions, necessitated by science, become a fait accompli. So when, in 2009, US President Barack Obama lifted the ban on federal funding for stem-cell research, he felt no need to make a moral, political case for the decision: ‘The promise that stem cells hold does not come from any particular ideology; it is the judgement of science.’ This is not to say that stem-cell research is a bad thing; rather, it is to say that a politician needs to make the case for it being a good thing.

Yet while there is plenty of critique in Get Real, there is plenty that is unquestioned, too. So no sooner has Glaser put scientism on the rack than, a few pages on, she’s espousing its most prominent manifestation: environmentalism. The chapter even begins with some all-too-persuasive facts from the mouths of Those To Whom We Must Defer: ‘Climate scientists generally agree that the safe limit for the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is 350 parts per million (ppm). As I write this, we’re already at 390ppm.’ She soon proceeds to read off a number of Malthus-heavy assertions passed off as fact: ‘Global warming, population explosion, peak oil, biodiversity in freefall: Planet Earth is facing unprecedented and multiple crises. It is little wonder, therefore, that as the situation becomes more desperate, self-deception becomes more attractive. If the world is turning into a desert, it’s tempting to put your head in the sand.’

It’s a bizarre reversal. Having eviscerated the deference towards science in one section, in another she proceeds to lambast those who resist the science for their ‘denialism’. It does not seem to occur to Glaser that a principal reason for opposing the environmental orthodoxy is that it attempts to pass off a moral and political argument about how we should live our lives — low-consumption, little procreation and an acceptance of economic stagnation — as a scientific necessity. Could there be a more flagrant form of the scientism that Glaser so eloquently takes to task elsewhere?