Published on 17 May 2015

In 1815, eight miles south of Brussels, two of history’s greatest generals met in battle for the first and only time: Napoleon Bonaparte, Emperor of the French, and the Duke of Wellington. The result was an epic, brutal battle that would decide the fate of Europe.

September 28, 2015

Epic History: Battle of Waterloo

June 24, 2015

Nathan Rothschild did as much to defeat Napoleon as Wellington

Matt Ridley decries his own taste in reading (too many cavalry charges and panzer tanks) and declares that we should honour the man who propped up the Duke of Wellington financially for making Wellington’s battlefield and diplomatic efforts meaningful:

Galloping bravely against an enemy, in however good a cause, is not the chief way the world is improved and enriched. The worship of courage as a pre-eminent virtue, which Hollywood shares with Homer, is oddly inappropriate today — a distant echo of a time when revenge and power, not justice and commerce, were the best guarantee of your security. Achilles, Lancelot and Bonaparte were thugs.

We admire achievements in war, a negative-sum game in which people get hurt on both sides, more than we do those in commerce, where both sides win.

The Rothschild skill in trade did at least as much to bring down Napoleon as the Wellesley skill in tactics. Throughout the war Nathan Rothschild shipped bullion to Wellington wherever he was, financing not just Britain’s war effort but also that of its allies, almost single-handedly. He won’t get much mention this week.

So I ought to prefer books about business, not bravery, because boring, bourgeois prudence gave us peace, plenty and prosperity. It was people who bought low and sold high, who risked capital, set up shop, saved for investment, did deals, improved gadgets and created jobs — it was they who raised living standards by ten or twentyfold in two centuries, and got rid of most child mortality and hunger. Though they do not risk their lives, they are also heroes, yet we have always looked down our noses at them. When did you last see an admirable businessman portrayed in a movie?

Dealing is always better than stealing, even from your enemies. It’s better than praying and preaching, the clerical virtues, which do little to fill bellies. It’s better than self-reliance, the peasant virtue, which is another word for poverty. As the economic historian Deirdre McCloskey put it in her book The Bourgeois Virtues: “The aristocratic virtues elevate an I. The Christian/peasant virtues elevate a Thou. The priestly virtues elevate an It. The bourgeois virtues speak instead of We”.

June 17, 2015

Bernard Cornwell talks about his recent book on Waterloo

Novelist Bernard Cornwell wrote a history of the battle of Waterloo and talks to John J. Miller about the book and the battle it describes here.

May 30, 2015

Waterloo, 1815

The Economist reviews some of the recent books published to co-incide with the two-hundredth anniversary of the Battle of Waterloo:

WITH the bicentenary of the battle of Waterloo fast approaching, the publishing industry has already fired volley after volley of weighty ordnance at what is indeed one of the defining events of European history. About that, there can be no argument. Waterloo not only brought to an end the extraordinary career of Napoleon Bonaparte, whose ambitions had led directly to the deaths of up to 6m people. It also redrew the map of Europe and was the climax of what has become known as the second Hundred Years War, a bitter commercial and colonial rivalry between Britain and France that had begun during the reign of Louis XIV. Through its dogged resistance to France’s hegemonic ambitions in the preceding 20 years, Britain helped create the conditions for the security system known as the Concert of Europe, established in 1815. The peace dividend Britain enjoyed for the next 40 years allowed it to emerge as the dominant global power of the 19th century.

If the consequences of the battle were both profound and mostly benign, certainly for Britain, the scale of the slaughter and suffering that took place in fields 10 miles (16km) south of Brussels on that long June day in 1815 remains shocking. The Duke of Wellington never uttered the epigram attributed to him: “Next to a battle lost, the greatest misery is a battle gained.” What he did say in the small hours after the battle was: “Thank God, I don’t know what it is like to lose a battle; but certainly nothing can be more painful than to gain one with the loss of so many of one’s friends.” Nearly all his staff had been killed or wounded. Around 200,000 men had fought each other, compressed into an area of five square miles (13 square kilometres).

When darkness finally fell, up to 50,000 men were lying dead or seriously wounded — it is impossible to say how many exactly, because the French losses were only estimates — and 10,000 horses were dead or dying. Johnny Kincaid, an officer of the 95th Rifles who survived the onslaught by the French on Wellington’s centre near La Haie Sainte farm, coolly declared: “I had never yet heard of a battle in which everybody was killed; but this seemed likely to be an exception, as all were going by turns.”

[…]

Four errors, partly the result of poor staff work, helped doom Napoleon. The first, entirely self-inflicted, was to deprive himself of his two most effective generals: Marshal Davout, left behind to guard Paris, and Marshal Suchet, put in charge of defending the eastern border against possible attack by the Austrians. The second was Ney’s almost inexplicable hesitation in taking the strategic crossroads of Quatre Bras, the key to dividing the coalition armies. The third was the aimless wandering in the pouring rain of the Compte d’Erlon and his 20,000 troops between the battle at Quatre Bras against the Anglo-Dutch and the battle at Ligny that the Prussians were losing. Had he intervened in either, the impact could have been decisive. The fourth was the failure of initiative by Grouchy that allowed the regrouped Prussians to outflank him and arrive at the critical moment to save Wellington at Waterloo.

That said, nothing should be taken away from Napoleon’s conquerors. Both commanders were talented professionals — Wellington was unmatched in the art of defence — who had experienced and competent subordinates and staffs. The British infantry and the King’s German Legion (a British army unit) were hardened veterans of the highest quality. Above all, both commanders trusted each other and never wavered in their mutual support, a factor that Napoleon almost certainly underestimated in his strategic calculus.

December 28, 2014

Edward Luttwak on Napoleon’s modernization of European law

In the London Review of Books, Edward Luttwak starts his review of Britain against Napoleon: The Organisation of Victory, 1793-1815 by Roger Knight by contrasting British and European views of Napoleon’s legacy:

I can recall few heated arguments with my father, but I remember very well our Napoleon quarrel. After two years at a British boarding school, I had learned a fair amount of English and just about enough history to mention Wellington and Waterloo as we were approaching Brussels on a drive from Milan. To my great surprise, my father burst out with a vehement attack on ‘the English’ for having selfishly destroyed Napoleon’s empire. Wherever it had advanced in Europe, modernity had advanced with it, sweeping away myriad expressions of obscurantism and hereditary privilege, emancipating the Jews and all manner of serfs, allowing freedom of, and from, religion, and offering opportunities for advancement for the talented regardless of their origins. I do not recall his actual words, and he would hardly have put it as I have here, but that was certainly his meaning, and I remember his equal-opportunity quotation: ‘Every French soldier carries a field-marshal’s baton in his knapsack.’ I also remember his explanation of the reason he accused the English of being ‘selfish’: Great Britain was already on its way to liberty and did not need Napoleon, but Europe did, and Britain took him away.

In other words, for Jozef Luttwak of Milano, formerly of Arad, Transylvania, as for many others on the Continent (and not only the French), all the wars of Napoleon, all his victories, counted for little in evaluating the man and his deeds. What counted was the progressive moderniser, the law-giver of the Code Napoléon of 1804, actually the Code civil des Français, which was really a civil code for Europeans, since Napoleon’s empire français extended across the Low Countries to Jutland and into northwest Italy, and took in the ex-Papal States and Dalmatia (as Illyria), adding up to a good part of Western Europe. Nor was Napoleon’s Code as ephemeral as his victories. It endures as the core of civil law not only in France but in its former European possessions, and their former possessions too, encompassing ex-French Africa, all of Latin America and the Philippines by way of Spain, and Indonesia by way of the Netherlands, as well as Quebec and Louisiana.

Even that list understates the influence of the code, and therefore of Napoleon the moderniser. Its text conveyed three powerfully innovative principles whose influence transcended by far its actual legal application, and which no restoration could undo: clarity, so that all could know their rights if they could read, without the recondite expertise of jurists steeped in customary law, with its hundreds of exemptions, privileges and eccentricities; secularism, which inter alia replaced parishes with municipalities, thereby introducing civil marriage, part of an entirely new form of individual and civic existence; and the right to individual ownership of property – which untied the immobilised holders of communal property – and employment free from servile obligations.

It mattered greatly that these revolutionary principles were proclaimed by Napoleon, already a conservative and commanding figure – unlike the revolutionaries of 1789, who could not give an aura of authority to their Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, which was itself soon challenged by the more egalitarian 1793 version, with both anyhow rejected by the upholders of privilege. In Napoleon’s vassal states (the Confederation of the Rhine, the Kingdoms of Spain, Italy and Naples, and the Grand Duchy of Warsaw), even where the code was not promulgated it was imitated, as was its drastically new style. Just as the florid convolutions and encrustations of rococo had been replaced by the linear elegance of the empire style, the thickets of customary law that Montesquieu had praised as barriers to despotism – as indeed they were, but only for privileged jurists – were replaced by the utterly systematic code, whose descending hierarchy of books, titles, chapters and sections that devolved into 2281 numbered paragraphs was itself infused with the new spirit of modernity. For Europeans of a liberal disposition, the code was a call to modernise not merely the law but society in its entirety – an impulse that would persist for decades.

August 27, 2014

The Congress System, the Holy Alliance and the re-ordering of Europe in the nineteenth century

In my ongoing origins of World War 1 series, I took a bit of time to discuss the Congress of Vienna and the diplomatic and political system it created for nearly one hundred years of (by European standards) peaceful co-existence. Not that it completely prevented wars (see the rest of the series for a partial accounting of them), but that it provided a framework within which the great powers could attempt to order affairs without needing to go to war quite as often. In the current issue of History Today, Stella Ghervas goes into more detail about the congress itself and the system it gave birth to:

Emperor Napoleon was defeated in May 1814 and Cossacks marched along the Champs-Elysées into Paris. The victorious Great Powers (Russia, Great Britain, Austria and Prussia) invited the other states of Europe to send plenipotentiaries to Vienna for a peace conference. At the end of the summer, emperors, kings, princes, ministers and representatives converged on the Austrian capital, crowding the walled city. The first priority of the Congress of Vienna was to deal with territorial issues: a new configuration of German states, the reorganisation of central Europe, the borders of central Italy and territorial transfers in Scandinavia. Though the allies came close to blows over the partition of Poland, by February 1815 they had averted a new war thanks to a series of adroit compromises. There had been other pressing matters to settle: the rights of German Jews, the abolition of the slave trade and navigation on European rivers, not to mention the restoration of the Bourbon royal family in France, Spain and Naples, the constitution of Switzerland, issues of diplomatic precedence and, last but not least, the foundation of a new German confederation to replace the defunct Holy Roman Empire.

[…]

Surprisingly, the Russian view on peace in Europe proved by far the most elaborate. Three months after the final act of the Congress, Tsar Alexander proposed a treaty to his partners, the Holy Alliance. This short and unusual document, with Christian overtones, was signed in Paris on September 1815 by the monarchs of Austria, Prussia and Russia. There is a polarised interpretation, especially in France, that the ‘Holy Alliance’ (in a broad sense) had only been a regression, both social and political. Castlereagh joked that it was a ‘piece of sublime mysticism and nonsense’, even though he recommended Britain to undersign it. Correctly interpreting this document is key to understanding the European order after 1815.

While there was undoubtedly a mystical air to the zeitgeist, we should not stop at the religious resonances of the treaty of the Holy Alliance, because it also contained some realpolitik. The three signatory monarchs (the tsar of Russia, the emperor of Austria and the king of Prussia) were putting their respective Orthodox, Protestant and Catholic faiths on an equal footing. This was nothing short of a backstage revolution, since they relieved de facto the pope from his political role of arbiter of the Continent, which he had held since the Middle Ages. It is thus ironic that the ‘religious’ treaty of the Holy Alliance liberated European politics from ecclesiastical influence, making it a founding act of the secular era of ‘international relations’.

There was, furthermore, a second twist to the idea of ‘Christian’ Europe. Since the sultan of the Ottoman Empire was a Muslim, the tsar could conveniently have it both ways: either he could consider the sultan as a legitimate monarch and be his friend; or else think of him as a non-Christian and become his enemy. As a matter of course, Russia still had territorial ambitions south, in the direction of Constantinople. In this ambiguity lies the prelude to the Eastern Question, the struggle between the Great Powers over the fate of the Ottoman Empire (the ‘sick man of Europe’), as well as the control of the straits connecting the Black Sea to the Mediterranean. Much to his credit, Tsar Alexander did not profit from that ambiguity, but his brother and successor Nicholas soon started a new Russo-Turkish war (1828-29).

July 29, 2014

Who is to blame for the outbreak of World War One? (Part two of a series)

Yesterday, I posted the first part of this series. Today, I’m dragging you a lot further back in time than you probably expected, because it’s difficult to understand why Europe went to war in 1914 without knowing how and why the alliances were created. It’s not immediately clear why the two alliance blocks formed, as the interests of the various nations had converged and diverged several times over the preceding hundred years.

Let me take you back…

To start sorting out why the great powers of Europe went to war in what looks remarkably like a joint-suicide pact at the distance of a century, you need to go back another century in time. At the end of the Napoleonic wars, the great powers of Europe were Russia, Prussia, Austria, Britain, and (despite the outcome of Waterloo) France. Britain had come out of the war in by far the best economic shape, as the overseas empire was relatively untroubled by conflict with the other European powers (with one exception), and the Royal Navy was the largest and most powerful in the world. France was an economic and demographic disaster area, having lost so many young men to Napoleon’s recruiting sergeants and the bureaucratic demands of the state to subordinate so much of the economy to the support of the armies over more than two decades of war, recovery from war, and preparation for yet more war. In spite of that, France recovered quickly and soon was able to reclaim its “rightful” position as a great power.

Dateline: Vienna, 1814

The closest thing to a supranational organization two hundred years ago was the Concert of Europe (also known as the Congress System), which generally referred to the allied anti-Napoleonic powers. They met in Vienna in 1814 to settle issues arising from the end of Napoleon’s reign (interrupted briefly but dramatically when Napoleon escaped from exile and reclaimed his throne in 1815). It worked well enough, at least from the point of view of the conservative monarchies:

The age of the Concert is sometimes known as the Age of Metternich, due to the influence of the Austrian chancellor’s conservatism and the dominance of Austria within the German Confederation, or as the European Restoration, because of the reactionary efforts of the Congress of Vienna to restore Europe to its state before the French Revolution. It is known in German as the Pentarchie (pentarchy) and in Russian as the Vienna System (Венская система, Venskaya sistema).

The Concert was not a formal body in the sense of the League of Nations or the United Nations with permanent offices and staff, but it provided a framework within which the former anti-Bonapartist allies could work together and eventually included the restored French Bourbon monarchy (itself soon to be replaced by a different monarch, then a brief republic and then by Napoleon III’s Second Empire). Britain after 1818 became a peripheral player in the Concert, only becoming active when issues that directly touched British interests were being considered.

The Concert was weakened significantly by the 1848-49 revolutionary movements across Europe, and its usefulness faded as the interests of the great powers became more focused on national issues and less concerned with maintaining the long-standing balance of power.

The European Revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the Spring of Nations, Springtime of the Peoples or the Year of Revolution, were a series of political upheavals throughout Europe in 1848. It remains the most widespread revolutionary wave in European history, but within a year, reactionary forces had regained control, and the revolutions collapsed.

[…]

The uprisings were led by shaky ad hoc coalitions of reformers, the middle classes and workers, which did not hold together for long. Tens of thousands of people were killed, and many more forced into exile. The only significant lasting reforms were the abolition of serfdom in Austria and Hungary, the end of absolute monarchy in Denmark, and the definitive end of the Capetian monarchy in France. The revolutions were most important in France, the Netherlands, Germany, Poland, Italy, and the Austrian Empire, but did not reach Russia, Sweden, Great Britain, and most of southern Europe (Spain, Serbia, Greece, Montenegro, Portugal, the Ottoman Empire).

The 1859 unification of Italy created new problems for Austria (not least the encouragement of agitation among ethnic and linguistic minorities within the empire), while the rise of Prussia usurped the traditional place of Austria as the pre-eminent Germanic power (the Austro-Prussian War). The 1870-1 Franco-Prussian War destroyed Napoleon III’s Second Empire and allowed the King of Prussia to become the Emperor (Kaiser) of a unified German state.

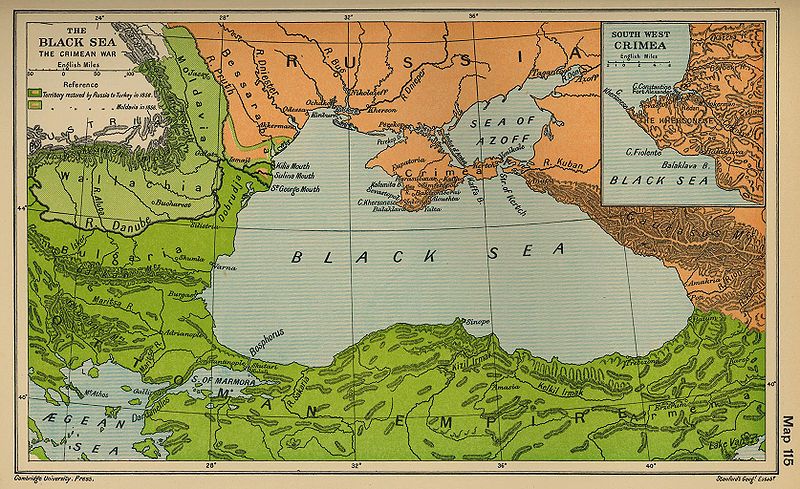

Russia’s search for a warm water port

Russia’s not-so-secret desire to capture or control Constantinople and the access from the Black Sea to the Mediterranean was one of the political and military constants of the nineteenth century. The Ottoman Empire was the “sick man of Europe”, and few expected it to last much longer (yet it took a world war to finally topple it). The other great powers, however, were not keen to see Russia expand beyond its already extensive borders, so the Ottomans were propped up where necessary. The unlikely pairing of British and French interests in this regard led to the 1853-6 Crimean War where the two former enemies allied with the Ottomans and the Kingdom of Sardinia to keep the Russians from expanding into Ottoman territory, and to de-militarize the Black Sea.

The Black Sea in 1856 with the territorial adjustments of the Congress of Paris marked (via Wikipedia)

Prussian Chancellor Otto von Bismarck talks with the captive Napoleon III after the Battle of Sedan in 1870.

In the wake of Napoleon III’s fall, France declared that they were no longer willing to oppose the re-introduction of Russian forces on and around the Black Sea. Britain did not feel it could enforce the terms of the 1856 treaty unaided, so Russia happily embarked on building a new Black Sea fleet and reconstructing Sebastopol as a fortified fleet base.

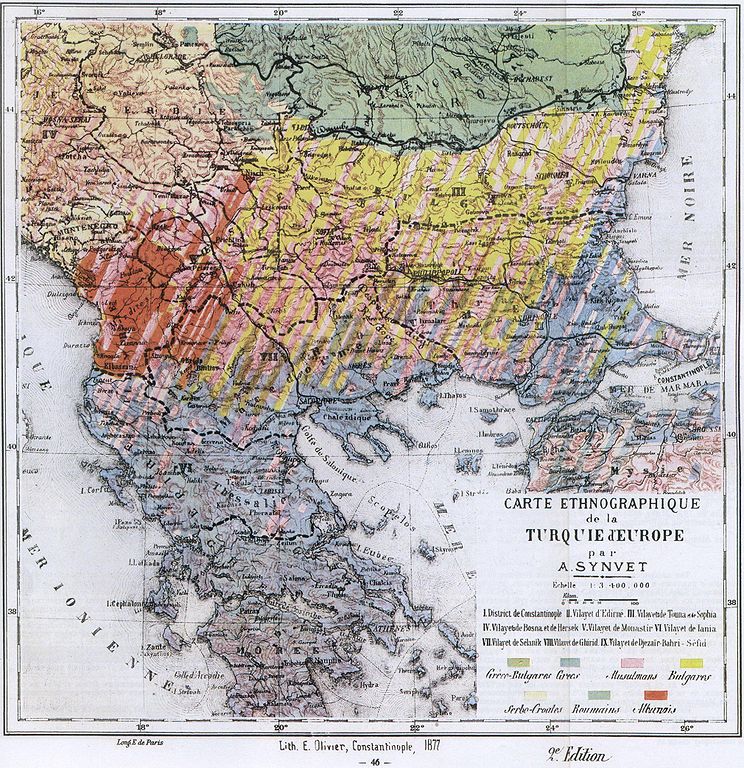

Twenty years after the Crimean War, the Russians found more success against the Ottomans, driving them out of almost all of their remaining European holdings and establishing independent or quasi-independent states including Bulgaria, Serbia, Montenegro, and Romania, with at least some affiliation with the Russians. A British naval squadron was dispatched to ensure the Russians did not capture Constantinople, and the Russians accepted an Ottoman truce offer, followed eventually by the Treaty of San Stefano to end the war. The terms of the treaty were later reworked at the Congress of Berlin.

Other territorial changes resulting from the war was the restoration of the regions of Thrace and Macedonia to Ottoman control, the acquisition by Russia of new territories in the Caucasus and on the Romanian border, the Austro-Hungarian occupation of Bosnia, Herzegovina and the Sanjak of Novi Pazar (but not yet annexed to the empire), and British possession of Cyprus. The new states and provinces addressed a few of the ethnic, religious, and linguistic issues, but left many more either no better or worse than before:

An ethnographic map of the Balkans published in Carte Ethnographique de la Turquie d’Europe par A. Synvet, Lith. E Olivier, Constantinople 1877. (via Wikipedia)

The end of the second post and we’re still in the 1870s … more to come over the next few days.

December 4, 2013

QotD: A nation of shopkeepers

When Napoleon called us “une nation de boutiquiers”, a nation of shopkeepers, he meant to insult us. Down the centuries, many Continentals have disparaged what they see as the soulless money-grubbing of the English-speaking peoples. Fascists and communists used remarkably similar language when they attacked “decadent Anglo-Saxon capitalism” — though, happily for the human race, it turned out not to be in decay at all.

It’s true that there was always a countervailing Anglophile tendency: Voltaire and Montesquieu, among others, admired us precisely because of our individualistic, mercantile, libertarian ways. But the idea that we “Anglo-Saxons” are too materialistic has never entirely gone away.

The phrase “Anglo-Saxons”, in this sense, is of course economic rather than racial. When the French talk of “les anglo-saxons” or the Spanish of “los anglosajones,” they don’t mean descendants of Æthelwulf or Oswine. They mean people who speak English and believe in small government, whether in Kowloon, Killarney or Kaukapakapa.

A nation of shopkeepers? Sounds good to me. What would you rather have? A nation of generals? Of civil servants? Of monks? Small employers are the greatest heroes we produce, and their heroism is all the greater for being unappreciated, unacknowledged, unthanked.

Daniel Hannan, “Shopkeepers have done more for human happiness than generals, statesmen or kings “, Telegraph, 2013-12-03

May 28, 2013

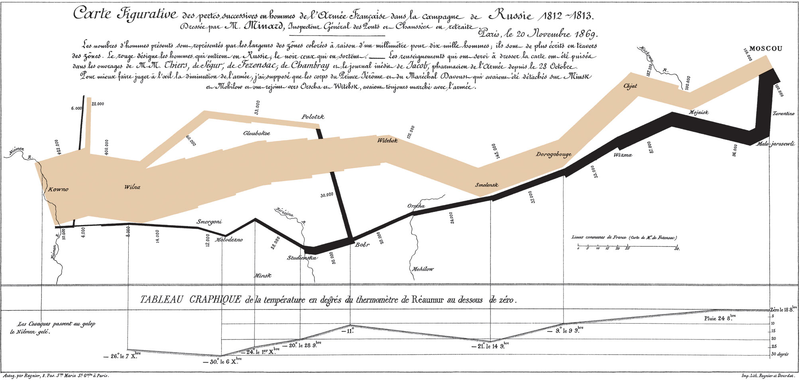

Charles Joseph Minard died for our (infographic) sins

Do you remember seeing the amazingly informative diagram by Charles Joseph Minard on the statistical side of Napoleon’s disastrous march on Moscow:

Charles Joseph Minard’s famous graph showing the decreasing size of the Grande Armée as it marches to Moscow (brown line, from left to right) and back (black line, from right to left) with the size of the army equal to the width of the line. Temperature is plotted on the lower graph for the return journey (Multiply Réaumur temperatures by 1¼ to get Celsius, e.g. −30 °R = −37.5 °C)

That is what a really good infographic can be. But, as Tim Harford points out, they’re not all that good:

Camouflage usually means blending in. That wasn’t an option for the submarine-dodging battleships of a century ago, which advertised their presence against an ever-changing sea and sky with bow waves and smokestacks. And so dazzle camouflage was born, an abstract riot of squiggles and harlequin patterns. It wasn’t hard to spot a dazzle ship but the challenge for the periscope operator was quickly to judge a ship’s speed and direction before firing a torpedo on a ponderous intercept. Dazzle camouflage was intended to provoke misjudgments, and there is some evidence that it worked.

Now let’s talk about data visualisation, the latest fashion in numerate journalism, albeit one that harks back to the likes of Florence Nightingale. She was not only the most famous nurse in history but the creator of a beautiful visualisation technique, the “Coxcomb diagram”, and the first woman to be elected as a member of the Royal Statistical Society.

Data visualisation creates powerful, elegant images from complex data. It’s like good prose: a pleasure to experience and a force for good in the right hands, but also seductive and potentially deceptive. Because we have less experience of data visualisation than of rhetoric, we are naive, and allow ourselves to be dazzled. Too much data visualisation is the statistical equivalent of dazzle camouflage: striking looks grab our attention but either fail to convey useful information or actively misdirect us.

[. . .]

Those beautiful Coxcomb diagrams are no exception. They show the causes of mortality in the Crimean war, and make a powerful case that better hygiene saved lives. But Hugh Small, a biographer of Nightingale, argues that she chose the Coxcomb diagram in order to make exactly this case. A simple bar chart would have been clearer: too clear for Nightingale’s purposes, because it suggested that winter was as much of a killer as poor hygiene was. Nightingale’s presentation of data was masterful. It was also designed not to inform but to persuade. When we look at modern data visualisations, we should remember that.

March 18, 2012

Can there ever be a “canonical” release of Abel Gance’s Napoleon?

Manohla Dargis charts the incredibly rocky history of Abel Gance’s silent masterpiece Napoleon:

SOON after Abel Gance’s “Napoleon” had its premiere in Paris in 1927, he wrote a letter to his audience, soliciting open eyes and hearts. “I have made,” he wrote, “a tangible effort toward a somewhat richer and more elevated form of cinema.” He had created a film towering in ambition, scale, cost, narrative and technical innovations, and believed that nothing less than “the future of the cinema” was at stake. His audacity had merit. The origins of the widescreen image can be traced to “Napoleon,” which also featured hand-held camerawork, eye-blink-fast editing, gorgeous tints, densely layered superimpositions and images shot from a pendulum, a sled, a bicycle and a galloping horse.

The film was an astonishment, and it was doomed. One hurdle was its length — his early versions ran from 3 hours to 6 hours 28 minutes (down from 9 hours) — while other difficulties were posed by Gance’s advances, specifically a process later called Polyvision that extended the visual plane into a panorama or three separate images and that required three screens to show it. Partly as a consequence, distributors and exhibitors took harsh liberties: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer cut it down to around 70 minutes for the American release, a butchering that seemed to encourage bad reviews. Gance continued to rework the film, adding sound for a 1935 version and, decades later, new material. Yet even as he was taking it apart, others — notably the British historian Kevin Brownlow — were trying to restore “Napoleon” to its original glory.

In truth “Napoleon,” as it was initially hailed, no longer exists, which raises ticklish questions about authorship. In his book on the film, Mr. Brownlow lists 19 versions of “Napoleon” — including those created by distributors, Gance and Mr. Brownlow himself, who for decades has tried to restore the long-lost full version.

It’s almost a metaphysical question: how can you re-create the “original” when even the creator was busy re-shaping it at every stage along the way? George Lucas looks like an arch-conservator in comparison to Gance’s efforts.