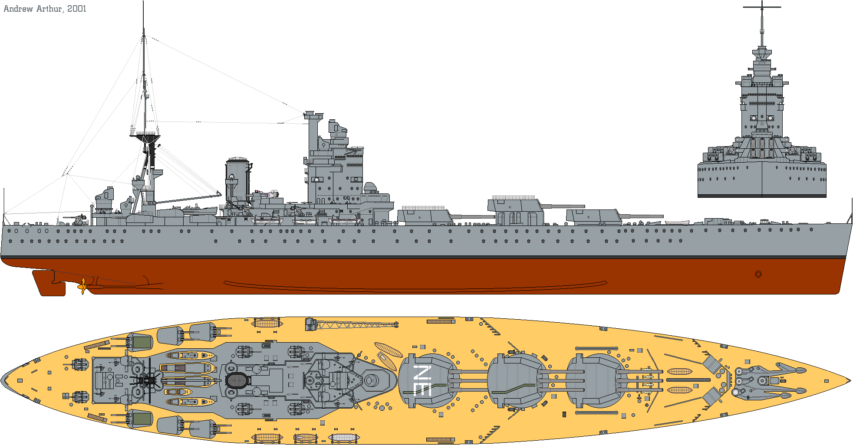

One of my favourite quirky ship designs is profiled at Naval Gazing: HMS Nelson and HMS Rodney. These two ships, known derisively by the names “Nelsol” and “Rodnol” (because of their odd profile resemblance to a class of RN oilers, whose names all ended in “-ol”), were the first post-WW1 British battleships designed to incorporate the bitter lessons learned at the battle of Jutland in 1916. Their construction was also influenced by the round of naval treaty talks that aimed to stop a renewed naval arms race and limit the major navies in both number and size of ships.

At the end of WWI, the Royal Navy faced a crisis. During the war, it had suspended new capital ship construction except for a handful of battlecruisers, while the American and Japanese building programs had continued to churn out ships that were more modern than the bulk of the British fleet. Worse, the British battlefleet had seen hard war service, and many of the early dreadnoughts were in bad shape and essentially unfit for further service. New battleships would be needed, ships that fully reflected the lessons of the war.

HMS Nelson off Spithead for the 1937 Fleet Review. Anchored in the background are two Queen Elizabeth-class battleships and two cruisers of the London class.

Photo via Wikimedia Commons.The most important of these was the need for an all-or-nothing armor scheme, as developed in the US. The war had seen major improvements in armor-piercing shells, and they required significantly more armor than previous vessels. However, the increased range gave designers a way out. Previously, the size of citadels had been set by the need to preserve stability and buoyancy if the ends were riddled. At long range, the many hits necessary to riddle the ends would not happen, and the citadel could be shrunk to thicken the armor. The British also looked to improve on the 15″ gun due to the proliferation of 16″ weapons in the American and Japanese navies. They investigated the triple turret, abandoned a decade earlier amid fears of increased mechanical complexity, and the 18″ gun under the cover name of 15″/B.

Two parallel design series were started, one for battleships, the other for battlecruisers. As this series was developed, the designers saw a serious problem with the battlecruisers. The boiler uptakes would leave large holes in the armored deck, and if the ship was headed towards the enemy, shells might be able to pass through the holes and into the aft magazines. The solution was to move all three turrets forward of the engines, on the basis of war experience showing that ships rarely if ever engaged targets directly aft.