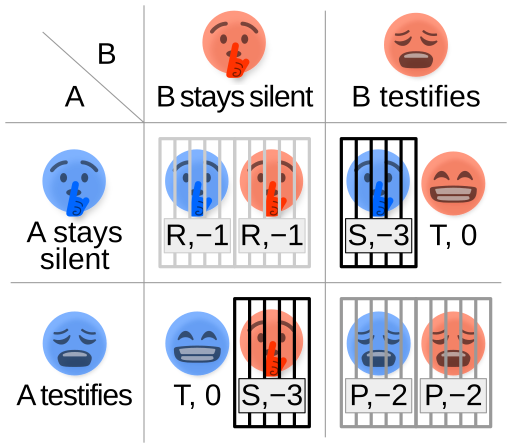

At Astral Codex Ten, Scott Alexander starts a post titled “The Early Christian Strategy” with some relevant back-story (fore-story?) involving game theory and the famous Prisoner’s Dilemma:

In 1980, game theorist Robert Axelrod ran a famous Iterated Prisoner’s Dilemma Tournament.

He asked other game theorists to send in their best strategies in the form of “bots”, short pieces of code that took an opponent’s actions as input and returned one of the classic Prisoner’s Dilemma outputs of COOPERATE or DEFECT. For example, you might have a bot that COOPERATES a random 80% of the time, but DEFECTS against another bot that plays DEFECT more than 20% of the time, except on the last round, where it always DEFECTS, or if its opponent plays DEFECT in response to COOPERATE.

In the “tournament”, each bot “encountered” other bots at random for a hundred rounds of Prisoners’ Dilemma; after all the bots had finished their matches, the strategy with the highest total utility won.

To everyone’s surprise, the winner was a super-simple strategy called TIT-FOR-TAT:

- Always COOPERATE on the first move.

- Then do whatever your opponent did last round.

This was so boring that Axelrod sponsored a second tournament specifically for strategies that could displace TIT-FOR-TAT. When the dust cleared, TIT-FOR-TAT still won — although some strategies could beat it in head-to-head matches, they did worst against each other, and when all the points were added up TIT-FOR-TAT remained on top.

In certain situations, this strategy is dominated by a slight variant, TIT-FOR-TAT-WITH-FORGIVENESS. That is, in situations where a bot can “make mistakes” (eg “my finger slipped”), two copies of TIT-FOR-TAT can get stuck in an eternal DEFECT-DEFECT equilibrium against each other; the forgiveness-enabled version will try cooperating again after a while to see if its opponent follows. Otherwise, it’s still state-of-the-art.

The tournament became famous because – well, you can see how you can sort of round it off to morality. In a wide world of people trying every sort of con, the winning strategy is to be nice to people who help you out and punish people who hurt you. But in some situations, it’s also worth forgiving someone who harmed you once to see if they’ve become a better person. I find the occasional claims to have successfully grounded morality in self-interest to be facile, but you can at least see where they’re coming from here. And pragmatically, this is good, common-sense advice.

For example, compare it to one of the losers in Axelrod’s tournament. COOPERATE-BOT always cooperates. A world full of COOPERATE-BOTS would be near-utopian. But add a single instance of its evil twin, DEFECT-BOT, and it folds immediately. A smart human player, too, will easily defeat COOPERATE-BOT: the human will start by testing its boundaries, find that it has none, and play DEFECT thereafter (whereas a human playing against TIT-FOR-TAT would soon learn not to mess with it). Again, all of this seems natural and common-sensical. Infinitely-trusting people, who will always be nice to everyone no matter what, are easily exploited by the first sociopath to come around. You don’t want to be a sociopath yourself, but prudence dictates being less-than-infinitely nice, and reserving your good nature for people who deserve it.

Reality is more complicated than a game theory tournament. In Iterated Prisoners’ Dilemma, everyone can either benefit you or harm you an equal amount. In the real world, we have edge cases like poor people, who haven’t done anything evil but may not be able to reciprocate your generosity. Does TIT-FOR-TAT help the poor? Stand up for the downtrodden? Care for the sick? Domain error; the question never comes up.

Still, even if you can’t solve every moral problem, it’s at least suggestive that, in those domains where the question comes up, you should be TIT-FOR-TAT and not COOPERATE-BOT.

This is why I’m so fascinated by the early Christians. They played the doomed COOPERATE-BOT strategy and took over the world.