AwakenWithJP

Published on Dec 19, 2017Bitcoin – Ultra Spiritual Life episode 86

In this video, I tell you all about Bitcoin, how it works, and why it’s guaranteed to be the best investment of your life.

January 31, 2018

Bitcoin – Ultra Spiritual Life episode 86

“Bitcoin is, of course, a mania – a delusion of the sort that human societies are prone to”

Tim Worstall looks at some historical manias and explains how even the maddest of them can yield long-term economic benefits (to society as a whole, if not to individual maniacs):

The UK’s railway mania, the tulip bubble, the dot com boom and other collective economic madness – such as bitcoin – might lose people a lot of money, but they often lay down important foundations

Bitcoin is, of course, a mania – a delusion of the sort that human societies are prone to. This is fighting talk from someone who declared in 2011 that bitcoin was all over. Being wrong is not interesting – it is rare things which are interesting, not common ones – but the psychology and economics here are important.

The classic text on this topic is Charles McKay’s Extraordinary popular delusions and the madness of crowds. Human societies are prone to manias which seem to defy any sense or reasonableness. Certainly markets can be so overcome, although the witch burnings show that it’s not purely an economic phenomenon.

The South Sea Bubble, Tulip mania, railway shares, the dotcom boom and now bitcoin are all part of that same psychological failing of not recognising that prices can and will fall as well as rise. That is the classical interpretation of the McKay book and observation, but modern studies take a more nuanced view.

South Sea and the Mississippi Company bubble were simply speculative frenzies, but the tulip story – while appearing very similar – can be read another way.

It is still true, for example, that a few sheds near Schipol, just outside Amsterdam, are the centre of the world’s trade in cut flowers – the result of that historical episode where a single tulip bulb became worth more than a year’s wages.

We can, and some do, take tourist trips to see the fields of those very tulips today. Modern researchers point out that the tulip was near unknown in Europe, the first examples only just having arrived from Turkey.

The art of cross-pollinating tulips to gain desirable characteristics was only just becoming generally known, and Europe was reaching a stage of wealth where the purely ornamental was becoming valuable.

Yes, the speculation in prices was ludicrous – although the weird stuff was in futures and options markets, not the physical trade, and the absurd prices never actually happened – but the end result of the frenzy was still that the tulip and flower market became and is centred in The Netherlands.

January 11, 2018

Sell the sizzle works, for a while, but even names with “blockchain” still have to produce something

Remember the media splash — and stock price boost — that the Long Island Iced Tea Company got by rebranding themselves as Long Blockchain? The rest of the plan apparently isn’t playing out quite as the company may have hoped:

… today Long Blockchain announced it was scrapping the stock offering. The company says that it’s still planning to buy bitcoin-mining hardware. However, Long Blockchain says that it “can make no assurances that it will be able to finance the purchase of the mining equipment.”

Where the company might get the money to buy the mining equipment is unclear. Antminer S9 mining hardware lists for upwards of $5,000, so it would cost millions of dollars to get 1,000 units. Long Blockchain’s most recent financial disclosure shows the company with only $429,000 in cash on hand in September.

The company’s press release didn’t explain the sudden turnaround, but it seems the stock market wasn’t thrilled by the plan to sell new shares. Long Blockchain’s stock price fell on Friday, the day the plan was announced, then soared this morning when the plan was scrapped. The stock is still worth more than double its value before the blockchain pivot was announced last month.

The broader question is why it makes sense for a beverage company to get into the blockchain business in the first place. In principle, you could imagine the company looking for ways to use blockchains to improve its core business — by optimizing supply chain management, for example.

Maybe I should rethink my plan to rebrand as Quotulatiousness BLOCKCHAIN…

January 6, 2018

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs meets the blockchain

Tim Worstall explains why sensible economists aren’t worried about robots taking all our jobs:

CryptoKitties is also so new that it needs explanation. It works on blockchain, so it’s sexy (Bitcoin!), although there’s no great reason why it should. It’s simply a collectible, as much as cigarette, football or baseball cards were. AN Cat exists digitally, others do too, they can breed and, as in a pretty standard Mendelian model, attributes are inherited to varying degrees.

People are willing to spend real money on gaining the attributes they want. All the blockchain element is doing is keeping track of who owns what – a pretty good use for blockchain even if a payment system might not be, an ownership registry being a different thing.

Apparently, 180,000 people are into collecting CryptoKitties now, having spent some $20m of real-world resources on their fun.

And this is why economists aren’t worried about automation leaving us with nothing to do. Partly, it’s this inventiveness on display, the things that humans will find to do. Breeding digital cats? But much more than that, it’s about the definition of value.

And here’s where Maslow enters the discussion:

there’s something called Maslow’s pyramid, often known as Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. We humans like our sleep, water, food and sex – and in roughly that order too. Only when one need earlier in the chain is at least partially sated will we get excited about finding more of the next. In a modern society most of these are well catered to, which is why we also desire, even demand, things further up the pyramid, such as TV shows, ballet, Simon Cowell, collectibles and so on.

It’s also true that economists insist this value is personal. It’s whatever value the individual places upon the whatever, market prices being the average of those summed. Just as we cannot say that one form of production creates more value than another, we cannot say that £10 of value in a collectible is lesser than £10 in food. We can, as in the pyramid, say that if the food desire isn’t partially sated then the collectible won’t be thought about, but order of desire isn’t the same as value.

All of which leads to “no worries she’ll be right” about automation. Say the robots do come in and steal all our jobs, and the algorithms do all the thinking – we’re not going to be left starving and bereft with nothing to do.

We’ll not be starving because the machines will now be doing everything. If they fail to do something as obvious as growing food, then we’ll all have jobs growing food. In fact, given the machines are making everything so efficient, we’ll all be stunningly rich – for all production must be consumed, that’s just an accounting identity.

But what are we going to do if we’ve not got those jobs? One answer is that we’ll start producing things further up the pyramid. More ballet, more poetry, more trifles like that. Why not? That’s what we’ve done every other time we’ve beaten the scarcity problem with more basic items, it’s the basis of civilisation. Only once we don’t need 100% of the people in the fields growing food can we have some portion of everyone off doing the civilisation bit.

But doesn’t this mean that we’re all going to end up doing terribly trivial things? Yep, it sure does. There are people out there making a very fine living from kicking a ball around, something that four centuries ago would have been considered total frivolity compared to growing food or chopping heads off enemies. The machine-driven future will have people doing what we today consider to be frivolous.

December 27, 2017

Will Hutton mansplains Blockchain … as he understands it

Tim Worstall tries to mitigate the damage caused by Will Hutton’s amazing misunderstanding of what blockchain technology is:

Will Hutton decides to tell us all how much Bitcoin and the blockchain is going to change our world:

Blockchain is a foundational digital technology that rivals the internet in its potential for transformation. To explain: essentially, “blocks” are segregated, vast bundles of data in permanent communication with each other so that each block knows what the content is in the rest of the chain. However, only the owner of a particular block has the digital key to access it.

So what? First, the blocks are created by “miners”, individual algorithm writers and companies throughout the world (with a dense concentration in China), who want to add a data block to the chain.

Will Hutton is, you will recall, one of those who insists that the world should be planned as Will Hutton thinks it ought to be. Something which would be greatly aided if Will Hutton had the first clue about the world and the technologies which make it up.

Blocks aren’t created by miners and individual algorithm writers, there is the one algo defined by the system and miners are confirming a block, not creating it. The blocks are not in communication with each other, they do not know what is in the rest of the chain – absolutely not in the case of earlier blocks knowing what is in later. It’s simply a permanent record of all transactions ever undertaken with an independent checking mechanism.

It’s entirely true that this could become very useful. But it’s really not what Hutton seems to think it is.

December 12, 2017

“Well sir, there’s nothing on Earth like a genuine, bona-fide, electrified, six-car blockchain!”

The way blockchain technology is being hyped these days, you’d think it was being pushed by the monorail salesman on The Simpsons. At Catallaxy Files, this guest post by Peter Van Valkenburgh is another of their informative series on what blockchain tech can do:

“Blockchain” has become a buzzword in the technology and financial industries. It is often cited as a panacea for all manner business and governance problems. “Blockchain’s” popularity may be an encouraging sign for innovation, but it has also resulted in the word coming to mean too many things to too many people, and — ultimately — almost nothing at all.

The word “blockchain” is like the word “vehicle” in that they both describe a broad class of technology. But unlike the word “blockchain” no one ever asks you, “Hey, how do you feel about vehicle?” or excitedly exclaims, “I’ve got it! We can solve this problem with vehicle.” And while you and I might talk about “vehicle technology,” even that would be a strangely abstract conversation. We should probably talk about cars, trains, boats, or rocket ships, depending on what it is about vehicles that we are interested in. And “blockchain” is the same. There is no “The Blockchain” any more than there is “The Vehicle,” and the category “blockchain technology” is almost hopelessly broad.

There’s one thing that we definitely know is blockchain technology, and that’s Bitcoin. We know this for sure because the word was originally invented to name and describe the distributed ledger of bitcoin transactions that is created by the Bitcoin network. But since the invention of Bitcoin in 2008, there have been several individuals, companies, consortia, and nonprofits who have created new networks or software tools that borrow something from Bitcoin—maybe directly borrowing code from Bitcoin’s reference client or maybe just building on technological or game-theoretical ideas that Bitcoin’s emergence uncovered. You’ve probably heard about some of these technologies and companies or seen their logos.

Aside from being in some way inspired by Bitcoin what do all of these technologies have in common? Is there anything we can say is always true about a blockchain technology? Yes.

All Blockchains Have…

All blockchain technologies should have three constituent parts: peer-to-peer networking, consensus mechanisms, and (yes) blockchains, A.K.A. hash-linked data structures. You might be wondering why we call them blockchain technologies if the blockchain is just one of three essential parts. It probably just comes down to good branding. Ever since Napster and BitTorrent, the general public has unfortunately come to associate peer-to-peer networks with piracy and copyright infringement. “Consensus mechanism” sounds very academic and a little too hard to explain a little too much of a mouthful to be a good brand. But “blockchain,” well that sounds interesting and new. It almost rolls off the tongue; at least compared to, say, “cryptography” which sounds like it happens in the basement of a church.

But understanding each of those three constituent parts makes blockchain technology suddenly easier to understand. And that’s because we can write a simple one sentence explanation about how the three parts achieve a useful result:

Connected computers reach agreement over shared data.

That’s what a blockchain technology should do; it should allow connected computers to reach agreement over shared data. And each part of that sentence corresponds to our three constituent technologies.

Connected Computers. The computers are connected in a peer-to-peer network. If your computer is a part of a blockchain network it is talking directly to other computers on that network, not through a central server owned by a corporation or other central party.

Reach Agreement. Agreement between all of the connected computers is facilitated by using a consensus mechanism. That means that there are rules written in software that the connected computers run, and those rules help ensure that all the computers on the network stay in sync and agree with each other.

Shared Data. And the thing they all agree on is this shared data called a blockchain. “Blockchain” just means the data is in a specific format (just like you can imagine data in the form of a word document or data in the form of an image file). The blockchain format simply makes data easy for machines to verify the consistency of a long and growing log of data. Later data entries must always reference earlier entries, creating a linked chain of data. Any attempt to alter an early entry will necessitate altering every subsequent entry; otherwise, digital signatures embedded in the data will reveal a mismatch. Specifically how that all works is beyond the scope of this backgrounder, but it mostly has to do with the science of cryptography and digital signatures. Some people might tell you that this makes blockchains “immutable;” that’s not really accurate. The blockchain data structure will make alterations evident, but if the people running the connected computers choose to accept or ignore the alterations then they will remain.

November 30, 2017

Bitcoin

Charles Stross explains why he’s not a fan of Bitcoin (and I do agree with him that the hard limit to the total number of Bitcoins sounded like a bad idea to me the first time I ever heard of them):

So: me and bitcoin, you already knew I disliked it, right?

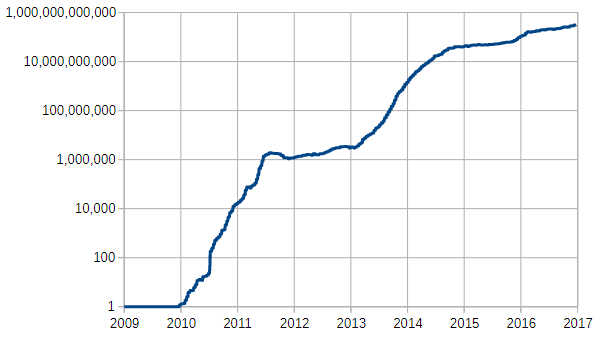

(Let’s discriminate between Blockchain and Bitcoin for a moment. Blockchain: a cryptographically secured distributed database, useful for numerous purposes. Bitcoin: a particularly pernicious cryptocurrency implemented using blockchain.) What makes Bitcoin (hereafter BTC) pernicious in the first instance is the mining process, in combination with the hard upper limit on the number of BTC: it becomes increasingly computationally expensive over time. Per this article, Bitcoin mining is now consuming 30.23 TWh of electricity per year, or rather more electricity than Ireland; it’s outrageously more energy-intensive than the Visa or Mastercard networks, all in the name of delivering a decentralized currency rather than one with individual choke-points. (Here’s a semi-log plot of relative mining difficulty over time.)

Bitcoin relative mining difficulty chart with logarithmic vertical scale. Relative difficulty defined as 1 at 9 January 2009. Higher number means higher difficulty. Horizontal range is from 9 January 2009 to 8 November 2014.

Source: Wikipedia.Credit card and banking settlement is vulnerable to government pressure, so it’s no surprise that BTC is a libertarian shibboleth. (Per a demographic survey of BTC users compiled by a UCL researcher and no longer on the web, the typical BTC user in 2013 was a 32 year old male libertarian.)

Times change, and so, I think, do the people behind the ongoing BTC commodity bubble. (Which is still inflating because around 30% of BTC remain to be mined, so conditions of artificial scarcity and a commodity bubble coincide). Last night I tweeted an intemperate opinion—that’s about all twitter is good for, plus the odd bon mot and cat jpeg—that we need to ban Bitcoin because it’s fucking our carbon emissions. It’s up to 0.12% of global energy consumption and rising rapidly: the implication is that it has the potential to outstrip more useful and productive computational uses of energy (like, oh, kitten jpegs) and to rival other major power-hogging industries without providing anything we actually need. And boy did I get some interesting random replies!

September 29, 2017

Blockchain primer – blockchain as a ledger

At Catallaxy Files, Sinclair Davidson provides some background knowledge of blockchain technology as a modern evolution of the simple ledger:

The blockchain is a digital, decentralised, distributed ledger.

Most explanations for the importance of the blockchain start with Bitcoin and the history of money. But money is just the first use case of the blockchain. And it is unlikely to be the most important.

It might seem strange that a ledger — a dull and practical document associated mainly with accounting — would be described as a revolutionary technology. But the blockchain matters because ledgers matter.

Ledgers all the way down

Ledgers are everywhere. Ledgers do more than just record accounting transactions. A ledger consists simply of data structured by rules. Any time we need a consensus about facts, we use a ledger. Ledgers record the facts underpinning the modern economy.

Ledgers confirm ownership. Property title registers map who owns what and whether their land is subject to any caveats or encumbrances. Hernando de Soto has documented how the poor suffer when they own property that has not been confirmed in a ledger. The firm is a ledger, as a network of ownership, employment and production relationships with a single purpose. A club is a ledger, structuring who benefits and who does not.

Ledgers confirm identity. Businesses have identities recorded on government ledgers to track their existence and their status under tax law. The register of Births Deaths and Marriages records the existence of individuals at key moments, and uses that information to confirm identities when those individuals are interacting with the world.

Ledgers confirm status. Citizenship is a ledger, recording who has the rights and is subject to obligations due to national membership. The electoral roll is a ledger, allowing (and, in Australia, obliging) those who are on that roll a vote. Employment is a ledger, giving those employed a contractual claim on payment in return for work.

Ledgers confirm authority. Ledgers identify who can validly sit in parliament, who can access what bank account, who can work with children, who can enter restricted areas.

At their most fundamental level, ledgers map economic and social relationships.

Agreement about the facts and when they change — that is, a consensus about what is in the ledger, and a trust that the ledger is accurate — is one of the fundamental bases of market capitalism.

[…]

The evolution of the ledger

For all its importance, ledger technology has been mostly unchanged … until now.

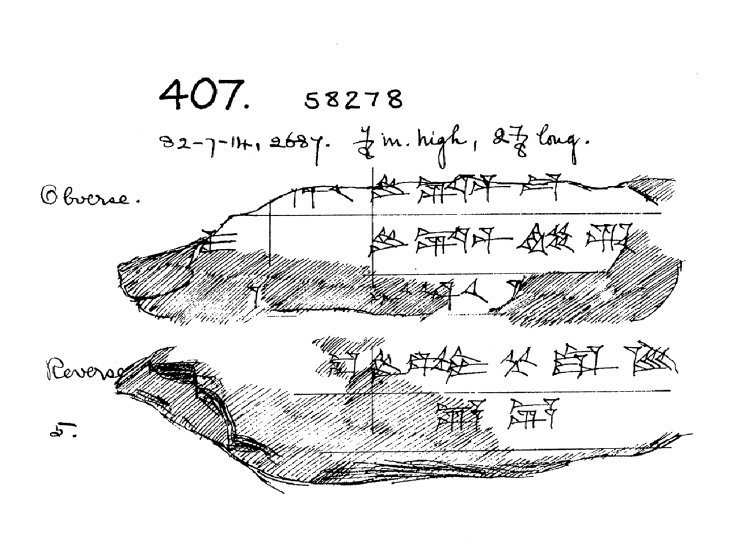

Ledgers appear at the dawn of written communication. Ledgers and writing developed simultaneously in the Ancient Near East to record production, trade, and debt. Clay tablets baked with cuneiform script detailed units of rations, taxes, workers and so forth. The first international ‘community’ was arranged through a structured network of alliances that functioned a lot like a distributed ledger.

The first major change to ledgers appeared in the fourteenth century with the invention of double entry bookkeeping. By recording both debits and credits, double entry bookkeeping conserved data across multiple (distributed) ledgers, and allowed for the reconciliation of information between ledgers.

The nineteenth century saw the next advance in ledger technology with the rise of large corporate firms and large bureaucracies. These centralised ledgers enabled dramatic increases in organisational size and scope, but relied entirely on trust in the centralised institutions.

In the late twentieth century ledgers moved from analog to digital ledgers. For example, in the 1970s the Australian passport ledger was digitised and centralised. A database allows for more complex distribution, calculation, analysis and tracking. A database is computable and searchable.

But a database still relies on trust; a digitised ledger is only as reliable as the organisation that maintains it (and the individuals they employ). It is this problem that the blockchain solves. The blockchain is a distributed ledgers that does not rely on a trusted central authority to maintain and validate the ledger.