In the latest SHuSH newsletter, confessed book-hoarder Ken Whyte has a confession to make:

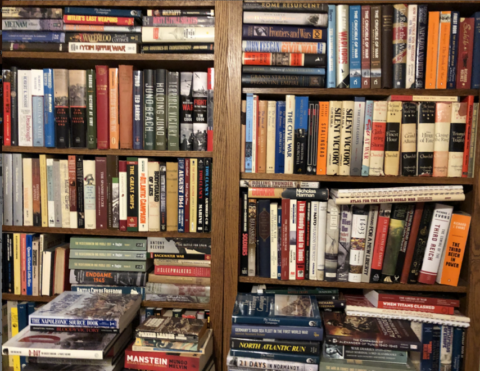

A small portion of my own book hoard. These shelves at least have a bit of commonality to them, unlike a lot of other shelves I could share.

I’ve been trying to reduce my hoard of books in recent months and it’s not going well.

And let’s be clear, it is a hoard, not a collection. A collection implies the books were selected with deliberation; that they are organized around subjects, themes, authors; that they are displayed with care. In a word, curated.

My books have been accumulated over time, some for work, some for pleasure. More were acquired impulsively than purposefully. Most people would not discern any organizational principles on my shelves. The fiction tends to be separate from the nonfiction, and books I’ve used to write books of my own tend to be grouped together, but not always. Hardbacks are mixed with paperbacks. I have some first editions that may be moderately valuable, although I’m not positive about that and I’ve never checked.

The hoard has been culled on occasion, usually in response to domestic complaints. The last major cull was a decade ago and since then I’ve been on a book diet, meaning that I can’t bring a new book home without getting rid of one already there.

I cheat on my diet all the time.

This part of the post could just as easily have been written by me … except that my sudden ejection from working life ten years back put me on an involuntary book-buying hiatus. From my peak buying years where I’d be accumulating multiple volumes per week, I was down to less than half a dozen new (or new-to-me) books through all of 2024.

That I’ve enjoyed a surplus of space for most of the last six years — the Sutherland House office is just two blocks from home — has abetted the cheating. The first week I took possession of the office, I lined it with solid metal shelves in optimistic anticipation of Sutherland House books to come. A good number of those shelves soon filled with boxes of personal books I could no longer keep at home and couldn’t bring myself to dump (along with a rather impressive archive of materials related to the founding of the National Post relocated from home to office for similar reasons).

Now Sutherland House is producing more books in one year than we produced in total over our first three years, and there are more of us in the office. Space is getting tight. I’ve been telling myself every weekend since before Christmas that I need to reduce the hoard.

It should not be difficult to jettison a quarter, a third, or even half of an impulsively amassed, haphazardly organized pile of books. You just face the shelf and pull out the ones you least want to keep. First to go are the never-cracked: anything that’s been sitting on the shelf for more than a decade without an attempt at reading. Next, books you’ve read and you know you’ll never want to read again. Then the yellowest paperbacks. Those three rules alone ought to get rid of half.

On a Saturday afternoon in mid-March. I faced a bookcase of eight shelves with about forty books per shelf. I challenged myself to get rid of one book for every book I kept. An hour later, I had half the books on the floor. Hurrah.

The next step was to put the unwanted books in boxes and haul them away.

They’re still sitting on the floor.

[Raises hand sheepishly] Yeah, I’ve got a few piles of books in various rooms of the house that failed the initial culling, yet somehow never made their way to the next stage of leaving the house.

I walk past them regularly and doubt my choices. I ask myself what harm would come from putting them all back on the shelves — makes more sense than leaving them on the floor. I wonder if a better solution to my storage problems wouldn’t be more shelves, or a storage locker.

I’ve read all the reasons why it’s difficult to get rid of books (or records, or art, or collections or hoards of any variety). The individual objects are companions, the scaffolding of your intellectual and emotional life, tokens of time, experience, identity, aspirations. Psychologists talk of loss aversion, the endowment effect that makes things feel more valuable simply because you own them, and the sunk-cost fallacy that leads you to hold onto and keep investing in things because you’ve already invested in them.

None of that makes me feel any better about my hoard (or the more than 10,000 photos and 30,000 emails I have on my laptop). The psychological explanations are just embarrassing.

When I’m levelling with myself, I can admit there are less than a hundred books I own where it genuinely matters to me to keep my particular copy. The rest are fungible. I freely admit that if I were to later miss any individual title I discarded, I could chase down a replacement in a day (in a minute electronically) at modest expense.

It used to matter to me to be surrounded by books in my living space. Now that I’m surrounded by books in my work space, not so much. For every instance when I spot a title on a shelf at home and think I really want to read that one someday, there are many more instances when I look at a whole shelf and think I’m never going to read any of these—they’re just taking up space. And I have a dust allergy, for christ sake.

Yet I can’t seem to do anything about it.