Wes O’Donnell talks about the thankfully never-launched invasion of the Japanese home islands at the end of the Second World War:

History often hinges on the narrowest of margins.

Entire nations can rise or fall based on decisions made under the pressures of the moment.

But what if those decisions had gone the other way?

What if Archduke Franz Ferdinand had survived the assassination attempt in 1914?

What if John F. Kennedy had lived to complete a second term?

And most intriguingly, what if the United States had not dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945?

The world would have witnessed Operation Downfall, the Allied invasion of Japan — an operation that, by all accounts, would have been the bloodiest amphibious assault in human history.

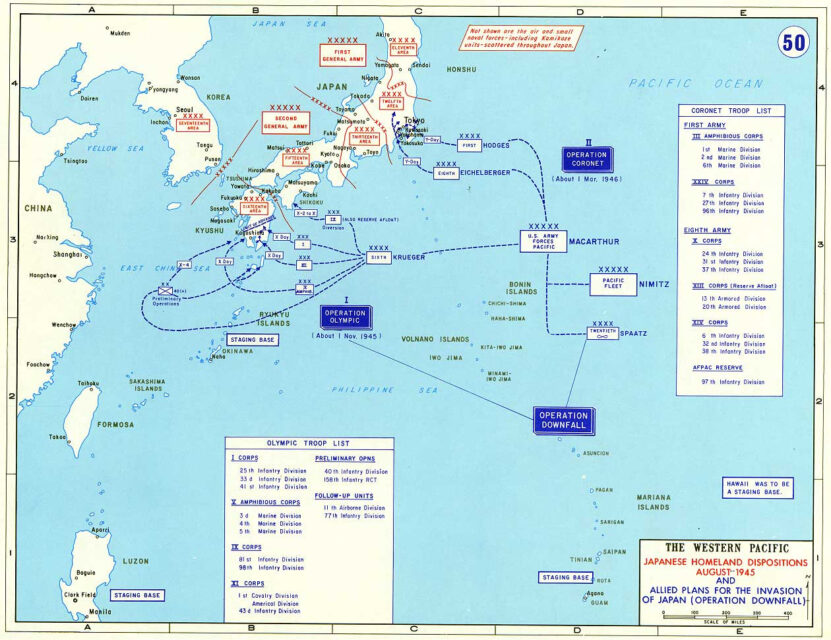

Operation Downfall was the codename for the proposed Allied plan for the invasion of Japan near the end of World War II.

The planned operation was abandoned when Japan surrendered following the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the Soviet declaration of war.

The operation had two parts: Operations Olympic and Coronet.

Set to begin in November 1945, Operation Olympic was intended to capture the southern third of the southernmost main Japanese island, Kyūshū, with the recently captured island of Okinawa to be used as a staging area.

Later, in the spring of 1946, Operation Coronet was the planned invasion of the Kantō Plain, near Tokyo, on the Japanese island of Honshu.

Airbases on Kyūshū captured in Operation Olympic would allow land-based air support for Operation Coronet.

The most troubling aspect of Downfall may have been the logistical problems facing military planners.

By 1945, there simply were not enough shipping, service troops, or engineers present to shorten the turnaround time for ships, connect the scattered installations across the Pacific, or build facilities like air bases, ports, and troop housing.

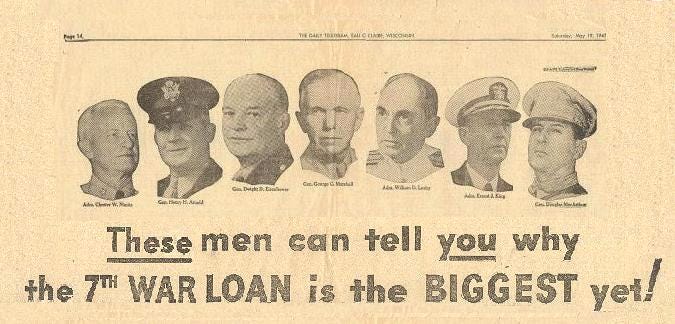

By this point in the war, the War Department had several military leaders that the government trusted to execute a quick end to hostilities.

Unlike the heavy political influence found in today’s wars, these men were given almost total freedom to plan large-scale military operations – Truman’s decision to drop the atomic bombs notwithstanding.

Six men of destiny

Responsibility for planning Operation Downfall fell to some of the most prominent American military leaders of the 20th century: Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz, General of the Army Douglas MacArthur, and the Joint Chiefs of Staff — Fleet Admirals Ernest King and William D. Leahy, along with Generals of the Army George Marshall and Hap Arnold, who commanded the U.S. Army Air Forces.

These six men, raised in the relatively stable and predictable world of late 19th-century small-town America, carried with them the values instilled by that era.

Arnold and MacArthur were West Point graduates; King, Leahy, and Nimitz came out of the Naval Academy; while Marshall honed his discipline at the Virginia Military Institute, a school renowned for its toughness, even more so than the service academies.

For these leaders, the concepts of duty, honor, and country were more than just words — they were guiding principles.

They approached their roles without a trace of cynicism, supremely confident in their ability and, crucially, their God-given right to steer the course of history, especially in the chaos of war.