In the latest SHuSH newsletter, Ken Whyte harks back to a time when brash young tech evangelists were lining up to bury the ancient codex because everything would be online, accessible, indexed, and (presumably) free to access. That … didn’t happen the way they forsaw:

By the time I picked up Is This a Book?, a slim new volume from Angus Phillips and Miha Kova?, I’d forgotten the giddy digital evangelism of the mid-Aughts.

In 2006, for instance, a New York Times piece by Kevin Kelly, the self-styled “senior maverick” at Wired, proclaimed the end of the book.

It was already happening, Kelly wrote. Corporations and libraries around the world were scanning millions of books. Some operations were using robotics that could digitize 1,000 pages an hour, others assembly lines of poorly paid Chinese labourers. When they finished their work, all the books from all the libraries and archives in the world would be compressed onto a 50 petabyte hard disk which, said Kelly, would be as big as a house. But within a few years, it would fit in your iPod (the iPhone was still a year away; the iPad three years).

“When that happens,” wrote Kelly, “the library of all libraries will ride in your purse or wallet — if it doesn’t plug directly into your brain with thin white cords.”

But that wasn’t what really excited Kelly. “The chief revolution birthed by scanning books”, he ventured, would be the creation of a universal library in which all books would be merged into “one very, very, very large single text”, “the world’s only book”, “the universal library.”

The One Big Text.

In the One Big Text, every word from every book ever written would be “cross-linked, clustered, cited, extracted, indexed, analyzed, annotated, remixed, reassembled and woven deeper into the culture than ever before”.

“Once text is digital”, Kelly continued, “books seep out of their bindings and weave themselves together. The collective intelligence of a library allows us to see things we can’t see in a single, isolated book.”

Readers, liberated from their single isolated books, would sit in front of their virtual fireplaces following threads in the One Big Text, pulling out snippets to be remixed and reordered and stored, ultimately, on virtual bookshelves.

The universal book would be a great step forward, insisted Kelly, because it would bring to bear not only the books available in bookstores today but all the forgotten books of the past, no matter how esoteric. It would deepen our knowledge, our grasp of history, and cultivate a new sense of authority because the One Big Text would indisputably be the sum total of all we know as a species. “The white spaces of our collective ignorance are highlighted, while the golden peaks of our knowledge are drawn with completeness. This degree of authority is only rarely achieved in scholarship today, but it will become routine.”

And it was going to happen in a blink, wrote Kelly, if the copyright clowns would get out of the way and let the future unfold. He recognized that his vision would face opposition from authors and publishers and other friends of the book. He saw the clash as East Coast (literary) v. West Coast (tech), and mistook it for a dispute over business models. To his mind, authors and publishers were eager to protect their livelihoods, which depended on selling one copyright-protected physical book at a time, and too self-interested to realize that digital technology had rendered their business models obsolete. Silicon Valley, he said, had made copyright a dead letter. Knowledge would be free and plentiful—nothing was going to stop its indiscriminate distribution. Any efforts to do so would be “rejected by consumers and ignored by pirates”. Books, music, video — all of it would be free.

Kelly wasn’t altogether wrong. He’d just taken a narrow view of the book. He was seeing it as a container of information, an individual reference work packed with data, facts, and useful knowledge that needed to be agglomerated in his grander project. That has largely happened with books designed simply to convey information — manuals, guides, dissertations, and actual reference books. You can’t buy a good printed encyclopedia today and most scientific papers are now in databases rather than between covers.

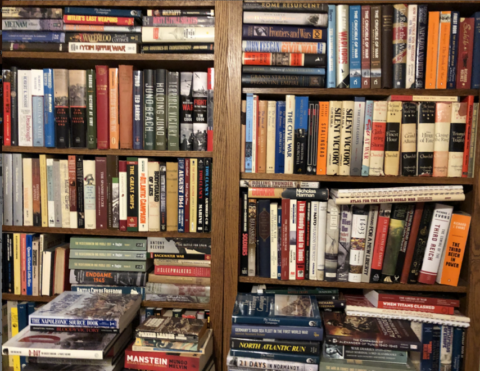

What Kelly missed was that most people see the book as more than a container of information. They read for many reasons besides the accumulation of knowledge. They read for style and story. They read to feel, to connect, to stimulate their imaginations, to escape. They appreciate the isolated book as an immersive journey in the company of a compelling human voice.