In Quillette, Aaron Sarin discusses what he calls the “Reverse Opium War” with Chinese drugs flooding the US street drug culture:

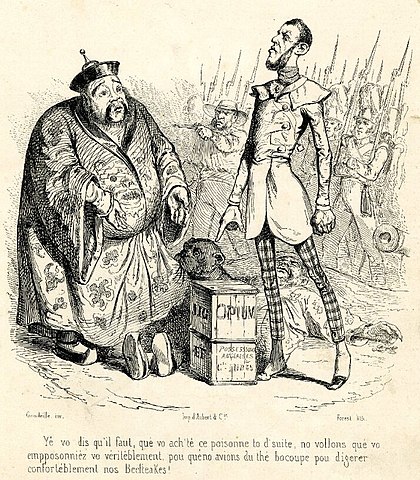

Jean-Jacques Grandville cartoon originally published in Charivari in 1840. “I tell you to immediately buy the gift here. We want you to poison yourself completely, because we need a lot of tea in order to digest our beefsteaks.”

Image and translated caption from Wikimedia Commons.

An epidemic is stalking American cities. Every day, men and women die on sidewalks, in bus shelters, on park benches. Some die sprawled in crowded plazas at midday; others die slumped in the corners of lonely gas station bathrooms. Internally, however, the circumstances are the same. They all end their lives swimming in the warm amniotic dream of a lethally dangerous opioid. When it comes, the moment of death is imperceptible: coaxed by the drug further and further from shore, the user simply floats out too far, passing some unmarked point of no return. The heartbeat weakens, the breathing slows and shallows. As soft an end as anyone might wish for.

This is the fentanyl crisis. It may seem strange to connect a very modern and very American phenomenon to a brace of wars waged 200 years ago by the British Empire on the last of the Chinese dynasties. But so the rhetoric runs: we are witnessing a Reverse Opium War; a belated Sinic revenge.

The Communist Party teaches schoolchildren that China was once a glorious superpower, until it was brought low by that subtlest and most devious of British weapons: Lachryma papaveris (poppy tears). Opium sapped the nation’s strength, and when the Chinese authorities banned it, then Britain went to war — twice.

Those wars crippled the Qing and heralded a “century of humiliation” for China — multiple military defeats and lopsided treaties, the Anglo-French looting and burning of the Emperor’s Summer Palace, the Japanese Rape of Nanking and lethal human experimentation by Unit 731 — ending only with the liberating forces of Marxism-Leninism in 1949. Now some commentators are telling us that history has inverted, that karma has kicked in.

Before examining this idea, we should remind ourselves of the American predicament. Ten years ago, fentanyl began its steady flow from China to the United States. Within just three years the drug had surpassed heroin to become the most frequent cause of American overdose deaths. Fentanyl is many times more powerful than heroin, and so there should be no surprise that lethality has spiked since the great Chinese flow began: in 2012, heroin topped the list with 6,155 deaths; by 2016, fentanyl was proving three times as deadly, with 18,335 deaths. The opioid’s influence seeps into all corners of the narcotics market, due to dealers hiding it in cocaine, heroin, and ecstasy. And it leaks across social strata, killing the homeless but also the rock star Prince, who passed away in an elevator at his Paisley Park estate after ingesting fentanyl disguised as Vicodin.

Under American pressure, the Chinese authorities agreed to regulate fentanyl analogs and two fentanyl precursor chemicals, but it soon turned out that shipments were being rerouted via Mexico. With this new arrangement, the crisis only deepened: between 2019 and 2021, the opioid killed 200 Americans a day. Last year alone, the DEA seized quantities of the drug equivalent to 410 million lethal doses. That’s enough to kill everyone in the US. Even a pandemic couldn’t stem the flow for long: in fact, Wuhan is one of the world’s most reliable suppliers of fentanyl precursors (a role it played both before and after starring at the eye of the COVID storm).

The booming fentanyl trade does not appear to rely on traditional criminal organisations, in the way that East Asian methamphetamine trafficking depends on the Triads. Instead, it turns out to be small family-based groups and legitimate businesses who manufacture and move the drug. Usually located on China’s south-eastern seaboard — Zhejiang, Fujian, Guangdong — these groups use the cover of the vast Chinese chemical industry to channel ingredients into the manufacture of fentanyl-class drugs and their precursors.