In The Critic, Michael Ledger-Lomas reviews a new book that is critical of Britain’s chronic case of nostalgia for “the good old days”:

Indulging in pained regret for lost times might seem a harmless pleasure, but Hannah Rose Woods is here to warn it has become a pathological “fixation”. The Right, she argues, has “weaponised” nostalgia, tapping “inchoate yearnings about fading pride and glory” to fuel hatred against historians who are simply “putting the facts back in” to the national “storybook”.

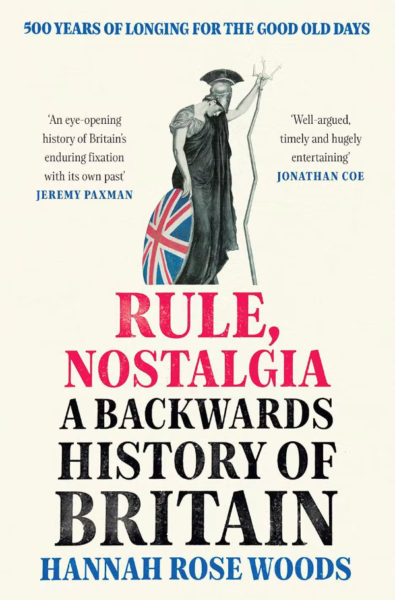

Apparently, the first cure for this “peculiarly English affliction” involves refuting errors and egregious simplifications in Tory talk about the national past. Woods is an inveterate Tweeter and her Rule, Nostalgia often works like a book-length version of the “Hi, historian here” threads that infest that medium.

The Government exhorted people to get through Covid by showing the Blitz spirit, but historians know German bombing caused as much fear and resentment as pride and resolve. Britons were supposed to Keep Calm and Carry On, “but this was a fantasy”, Woods writes, because the 1940s poster with that motto never entered circulation. The tea towels lied to us.

Woods is more productive when she probes nostalgia as a cluster of emotions, rather than condemning it as a set of errors. For like all emotions, it can be usefully historicised. This insight shapes the basic structure and approach of the book, which is more ironic than irate. Our times seem to be gripped by nostalgia for the days before yesterday, but the sixties, seventies and eighties abounded with yearning for the simplicities of the Second World War.

The thirties and forties were, in turn, full of voices lamenting what one of Orwell’s heroes called the “newness of everything”, pining for the sun-dappled afternoons of Edwardian England. The Edwardians themselves lamented the lost certainties of the high Victorian age and fretted that rural tranquillity was on the wane. And so on. Woods turns the periods of our history into Russian dolls of nostalgia, each nested within the other.

It is an engaging literary device which palls as succeeding chapters ask readers to re-enact their surprise that apparently stable times were consumed with anxiety about losing touch with tradition. Woods says the “calmly elegant Georgian heyday” fretted about whether Britain should go global or remain a tight little island, while it would be a “hard sell” to claim that the age of the Reformation and the Civil War was an “age of contentment and stability”. Well, quite.

The further Woods progresses away from the “rancid Englishness” of the present, the more forgiving she becomes of nostalgia — or at least of wistful absorption in the past, which is not quite the same thing. She rightly sees that nostalgia has generally not been an obstacle to rapid social change — what bolder Victorians would have called “progress” — but has offered psychological compensation for them.