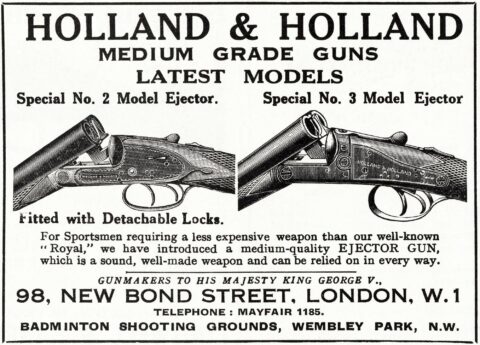

In The Critic, Patrick Galbraith talks to the current head of the Beretta company, which took over Britain’s Holland & Holland:

On the steps up to the blue door a man in a faded red tracksuit leans on one of the stone pillars in the Monday morning sun. All down Jermyn Street windows have been thrown open and flags above shop doors hang still in the heat.

I knock three times then push a bottle of Sudafed up my nose, squeeze twice, and lick at the bitter liquid as it runs over my lip. I was 20 before I ever experienced hay fever. I was fishing somewhere I shouldn’t have been when it first hit. I’ve not enjoyed June much since.

When I get up there, Franco Gussalli Beretta is sitting in the middle of the room in a puddle of sunlight: blue suit, thick grey hair, and a trio of arrows on his big silver belt buckle, the logo of a business established by his ancestor in Lombardy almost 500 years ago.

The earliest documented order was from the Venetian Republic for 185 barrels: “296 ducats made payable to Bartolomeo Beretta”. Fifteen generations later, Franco oversees the production of 1,500 guns a day, from grenade launchers to the ubiquitous “Silver Pigeon”, probably the most popular shotgun in the world.

The current generation are aggressively acquisitive. In recent years they’ve bought a German optics firm, a Finnish rifle manufacturer, and an American company that makes replicas of the sort of weapons that won the West — my own cowboy costume has been too small for some time.

Then, last February, Beretta made their boldest move yet by buying Holland & Holland, the finest gunmaker in London. Franco is a likeable man: he speaks at twice the volume he needs to and he laughs more loudly still. He loves cars and art and boats, and he admits that the day there’s a Beretta running the business who isn’t passionate about guns will be the day it all goes bang. What Holland & Holland needs, he reckons, is innovation.

British gunmakers have been stuck in the late nineteenth century for over a hundred years now and it might just be that Franco has the coglioni to make it new. We talk for half an hour and then as I’m standing to go, Carlo walks in — nonchalant at 25, a black t-shirt, dark sunglasses and jeans. Bartolomeo’s 16 times great-grandson. Franco gestures towards him and asks if I have any questions for the boy. Carlo talks to me briefly about NFTs but then tells me the real struggle is going to be a political one. He wants to make the world understand that hunting can be part of conservation. “And do you hunt?” I ask, thinking we might swap rabbit recipes. He shakes his head and tells me that as crazy as it sounds he doesn’t get out very much: “In Italy, young people don’t hunt so much anymore.”