Instapundit linked to a news release on a recent Cambridge study on the plague which devastated the Byzantine Empire during the reign of Justinian I, but which may have come through an as-yet undiscovered northern European path that reached the British Isles well before appearing within the Eastern Roman territories:

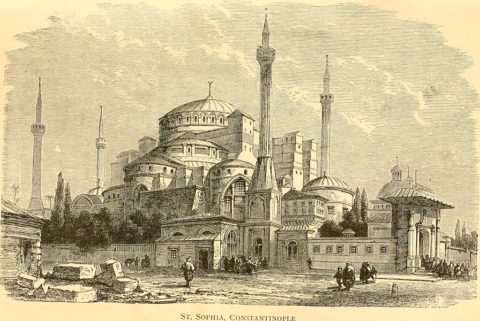

Illustration of the Hagia Sophia from European History: An outline of its development by George Burton Adams, 1899.

Wikimedia Commons

“Plague sceptics” are wrong to underestimate the devastating impact that bubonic plague had in the 6th–8th centuries CE, argues a new study based on ancient texts and recent genetic discoveries.

The same study suggests that bubonic plague may have reached England before its first recorded case in the Mediterranean via a currently unknown route, possibly involving the Baltic and Scandinavia.

The Justinianic Plague is the first known outbreak of bubonic plague in west Eurasian history and struck the Mediterranean world at a pivotal moment in its historical development, when the Emperor Justinian was trying to restore Roman imperial power.

For decades, historians have argued about the lethality of the disease; its social and economic impact; and the routes by which it spread. In 2019-20, several studies, widely publicised in the media, argued that historians had massively exaggerated the impact of the Justinianic Plague and described it as an “inconsequential pandemic”. In a subsequent piece of journalism, written just before COVID-19 took hold in the West, two researchers suggested that the Justinianic Plague was “not unlike our flu outbreaks”.

In a new study, published in Past & Present, Cambridge historian Professor Peter Sarris argues that these studies ignored or downplayed new genetic findings, offered misleading statistical analysis and misrepresented the evidence provided by ancient texts.

Sarris says: “Some historians remain deeply hostile to regarding external factors such as disease as having a major impact on the development of human society, and ‘plague scepticism’ has had a lot of attention in recent years.”

Sarris, a Fellow of Trinity College, is critical of the way that some studies have used search engines to calculate that only a small percentage of ancient literature discusses the plague and then crudely argue that this proves the disease was considered insignificant at the time.

Sarris says: “Witnessing the plague first-hand obliged the contemporary historian Procopius to break away from his vast military narrative to write a harrowing account of the arrival of the plague in Constantinople that would leave a deep impression on subsequent generations of Byzantine readers. That is far more telling than the number of plague-related words he wrote. Different authors, writing different types of text, concentrated on different themes, and their works must be read accordingly.”