In the latest edition of his Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes outlines the “push” and “pull” theories to account for the vast growth of London and how that urban growth strongly encouraged specialization in English agriculture to feed the great city:

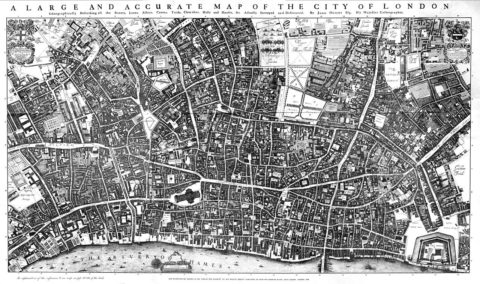

The 1677 original of this map is 8 feet 5 inches by 4 feet 7 inches, in 20 sheets. In 1894 the British Museum granted permission to the London and Middlesex Archaeological Society to make a reduced copy, of which the original of this scan is a copy. The L&M Society copy apparently did not match the dissected sheets perfectly, and the misjoins can be seen in places in this reproduction.

Scanned copy of reproduction in Maps of Old London (1908) of Ogilby & Morgan’s Map of London.

Something significant happened to the English countryside in the century before 1650. Although England’s population merely recovered to its pre-Black Death high of about 5 million, the economy was transformed. Having once been an overwhelmingly agrarian society, by 1650 a small but unprecedented proportion of the population now lived in cities, and less than half of the workforce was employed in agriculture. The country had de-agrarianised, and most remarkably of all, its food was still grown at home.

[…]

One possibly explanation is that there was some special change in England’s agricultural technology that increased its productivity, requiring fewer and fewer people, and possibly even driving them off the land, so that they were forced to find alternative employment. This thesis comes in various forms, many of which I’m still coming to grips with, but broadly speaking it implies a “push” from the fields, and into industry and the cities. Desperate, and unable to demand high wages, these cheaper workers should have stimulated industry’s growth.

The alternative, however, is that there was nothing very special or innovative about English agriculture, and that instead there was an even larger increase in the demand for workers in industry and services. The thesis implies a “pull” into industry and the cities, causing people to abandon agriculture for more profitable pursuits, and thereby making England’s agriculture de facto more productive — something that may or may not have actually been accompanied by any changes to agricultural technology, depending on how much slack there was in how the labourers or land had been employed.

The push thesis implies agricultural productivity was an original cause of England’s structural transformation; the pull thesis that it was a result. The evidence, I think, is in favour of a pull — specifically one caused by the dramatic growth of London’s trade.

Even though the population eventually recovered from the massive impact of the Black Death, not all of the land that was under plough was returned to active farming and a much greater diversity of uses for rural land emerged, including more pastures for grazing livestock, and small cash crops to be sold into the cities (especially into London).

With the dramatic growth of London in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the more intensive methods came to be in much higher demand. Indeed, the extraordinary pull of the city’s growth resulted in English agriculture becoming increasingly specialised. Not only were there millions of acres of pasture still left that could be returned to the plough, but despite the relative fall in the prices of livestock, some areas actually became even more devoted to pasture. Many of the villages that had been abandoned after the Black Death were, even by the 1870s, over half a millennium later, still not being farmed. With wealthy Londoners demanding more varied diets, with meat and dairy, the various regions of England discovered their comparative advantages rather than all shifting to grain. There was thus extra room for agriculture to become more productive simply by devoting the best land for pasture to pasture, and the best soils for arable to arable, then trading the produce with one another, rather than have each area try to be self-sufficient. It’s something we also see in the decline of grains like rye, especially near London, to be replaced by wheat — the switching of a crop best-suited to local subsistence, to one that could be sold elsewhere and in bulk for cash.

In general, the south and east of England became increasingly arable, while the north-west concentrated on pasture. Yet there were also exceptions to be made for London’s particular wants. Thus, county Durham converted more land to arable to feed the miners of Newcastle coal, used to heat London’s homes; and the county of Middlesex, now largely disappeared under London’s own expansion, specialised in pasture for horses, rather than feeding people, so as to feed the city’s main sources of transportation. As the writer Daniel Defoe put it in the 1720s, “this whole Kingdom, as well the people, as the land, and even the sea, in every part of it, are employed to furnish something, and I may add, the best of everything, to supply the city of London with provisions.”