At Works in Progress, Scott Alexander looks at the details of rates of depression (which went up during the pandemic) and suicides (which surprisingly went down):

When COVID started spreading, life got more depressing, people became more depressed, but suicide rates went down. Why?

First, are we sure all of that is true? I won’t waste your time listing the evidence that life got more depressing, but what about the other two?

Ettman et al. conveniently had data from nationally representative surveys about how many Americans were depressed before COVID-19. They found another nationally representative sample and asked them the same questions in late March/early April 2020, when the first wave of US cases and lockdowns was at its peak. They found that 3 times as many people had at least one depression symptom, and 5–10x as many people scored in the range associated with “moderately severe” or “severe” depression.

This is a good study. It’s published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, a good journal. It’s been cited 50+ times in 6 months. Really the only thing anyone could have against it is the implausibly large effect it found. But it matches similar studies from Australia, Portugal, and around the world. Let’s say it’s real.

Along with the increased depression came an increase in people who said they were thinking about suicide. According to the US CDC, more than twice as many Americans considered suicide in spring 2020 compared to spring 2018 (10.7% vs. 4.3%).

Yet completed suicide rates stayed flat or declined. It’s hard to tell exactly which, because suicide is rare and noisy, and you need lots of data before anything starts looking statistically significant. But there are studies somewhere between “flat” and “declined” from Norway, England, Germany, Sweden, and New Zealand.

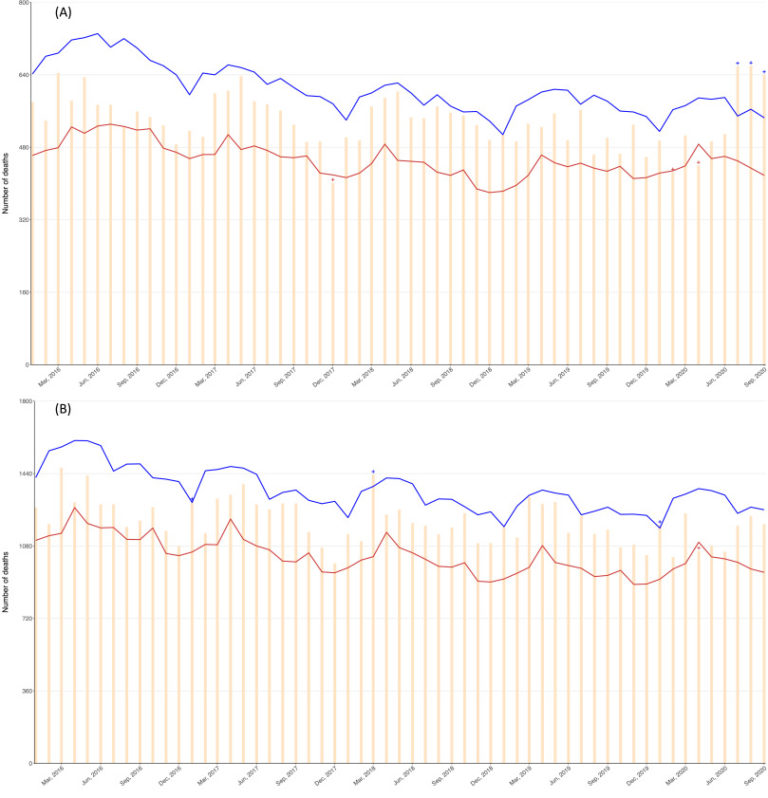

We also have two more complete reports from larger countries that help us see the pattern in more detail. First is Japan. Studies by Tanaka and Nomura broadly agree on a similar pattern — a slight decrease in suicides in the earliest stage of the pandemic (spring 2020) followed by a larger increase during the autumn. Here’s Nomura’s data:

The top graph is women, the bottom is men. The blue and red lines represent the 95% confidence range for an “average” year. Months that differ significantly from the average have little dots on top of their bars. You can see that April 2020 had significantly less suicide than average, among both genders, and July/August/September have more than average for women (and trend on the high side for men too).

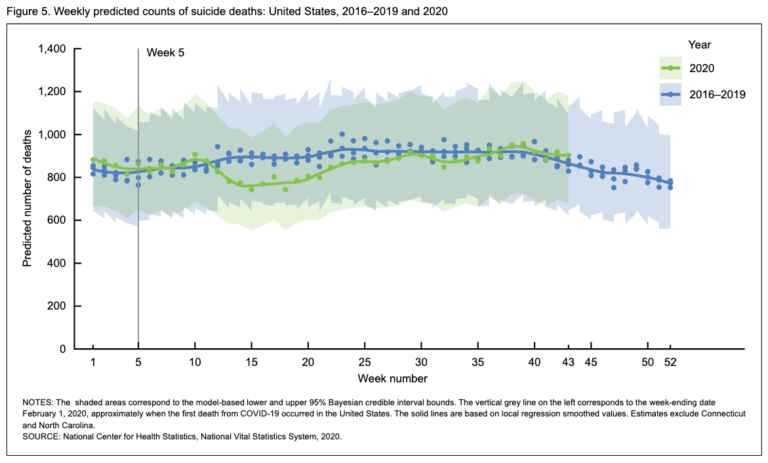

Second is the US. The US Centers for Disease Control recently released their “nowcast” of 2020 deaths. These use the limited amount of data they have now to predict what the trends will look like once all the data comes in; their prediction process seems reasonable and we can probably treat the figures as canonical. Here’s their main result:

Suicide rates were pretty normal until March, when they dropped off pretty quickly and stayed low until midsummer. They’ve since hovered around normal again. Overall, suicides declined by 5.6%.

All these countries combine to form a picture of suicide rates dipping very slightly during the first and most frantic period of the pandemic — March to May — and then going back to normal (except in Japan, where things have since gotten worse). Thus the paradox: increasing depression combined with decreasing suicides. What’s going on?