In The Critic, Nigel Jones considers some of the great orators of history:

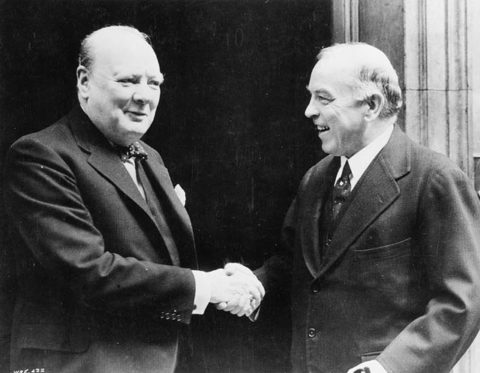

Prime Minister Winston Churchill greets Canadian PM William Lyon Mackenzie King, 1941. Churchill was certainly one of the great orators of history … Mackenzie King, on the other hand, certainly was not.

Photo from Library and Archives Canada (reference number C-047565) via Wikimedia Commons.

On 19 November 1863, President Abraham Lincoln rose to speak at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, the battlefield which four and a half months before had seen the decisive turning point of the American Civil War. Lincoln was not even the principal speaker at the ceremony to dedicate a cemetery for those who had fallen in the battle.

Before he spoke, the President had to sit through a two-hour address by a pompous official orator, a windbag called Edward Everett. But when he finally got to his feet Lincoln entered political immortality. He spoke for only two minutes, but the few words he uttered about “Government of the people, by the people, and for the people” have echoed down the years – even Mrs Thatcher made a recording of them – inspiring and rousing generations to value and defend democracy.

Winston Churchill’s iconic status as Britain’s greatest Prime Minister largely rests on the handful of radio speeches he growled out to the nation in the darkest days of World War Two: “… fight them on the beaches … so much owed by so many to so few … this was their finest hour …” and so on.

Ever since Roman statesmen such as Cato and Cicero delivered their speeches on the Capitol, oratory like that spoken by Lincoln and Churchill has been a mainstay of western civilisation and governance. A carefully constructed argument or a few ringing phrases having the power to change minds, stiffen sinews, and bring down leaders.

Churchill himself was brought to supreme political power in 1940 by the power of the spoken word. Those words were spoken by one politician – his friend and schoolmate Leo Amery – quoting another, when Amery repeated Oliver Cromwell’s words dismissing the Long Parliament in calling for the end of Neville Chamberlain’s feeble administration: “You have sat here too long for any good you have been doing. Depart, I say, and let us have done with you: in the name of God, go!” Chamberlain, albeit reluctantly, went.