Melanie McDonagh reviews the re-released early work by Douglas Murray:

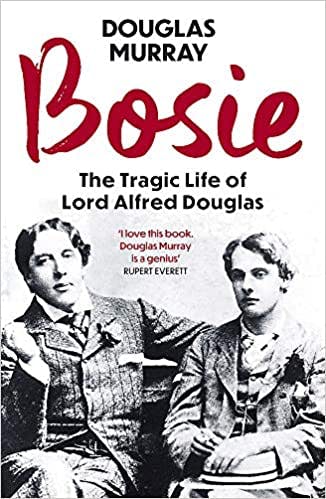

It would probably have been better for Lord Alfred Douglas to have died young. Had he died when he was still beautiful and youthful looking, he would have remained forever the gilded youth Oscar Wilde loved. That golden Alfred Douglas survives in the famous photograph on the front of Douglas Murray’s book, with Wilde sitting near Bosie, his arm extended behind the boy with something like possessiveness. Instead the boy survived until 1945, worn, lonely and poverty-stricken, his looks withered, his nose pinched, contemptuous of modernity, but still with a redemptive, blistering integrity.

Twenty years after it was first written, Douglas Murray has reissued his fine biography of Bosie: his first book, written in his gap year before he went to Oxford. Looking back now on his precocious work, he thinks he overdid a little his enthusiasm for Douglas’s poetry, understated his toxic anti-Semitism and didn’t quite do justice to the pederastic element of his early sexuality – as Bosie preferred to put it, his tastes were for youth and softness. In practice this could mean 14-year-old boys, even younger, at a time when he and Wilde had reunited following Wilde’s release from prison. Actually, I think Murray’s original estimate of Alfred Douglas’s sonnets was absolutely right; they vary in quality, but as he said, at their best they equalled the poets he most venerated.

Trouble is, not many people think of Alfred Douglas as a poet, even though they might unknowingly quote perhaps his most famous line, about the love that dares not speak its name. But there were literary critics in his own day who compared him to Shakespeare as a writer of sonnets. Remarkably he has fallen almost entirely off the literary radar now, known only as a player in Wilde’s drama, and it is a pity that the success of this biography hasn’t changed that.

One of the services Douglas Murray performs in his biography is simply to reproduce some of his finest verses so we can judge it for ourselves. Indeed, while writing the book he managed to persuade the Home Office to release the copybook in which Alfred Douglas wrote his prison verses, In Excelsis, which the authorities refused to do in his lifetime.

Even in his own time, most people thought of him as the lover of Oscar Wilde, a byword for a bugger, the boy who brought about Wilde’s destruction through the vengeful malice of his unbalanced father. That perception was powerfully reinforced by Wilde’s terrible letter written from prison, De Profundis, in which he empties his bitterness against the youth he loved in an outpouring of emotion which was in many respects unjust and untrue, especially about Bosie’s financial support for Wilde. Fatally, the letter was never given to him by Robert Ross, Wilde’s friend, and only released in full during a devastating court case.