Hannah Betts explains why it’s now somewhere between awkward and mortally offensive to use the word “flattering” to or about a member of Gen Z:

Why do we wear clothes? The mundane answer runs “for protection against the elements”, pointing to the succession of Ice Ages to which homo sapiens was subjected, forced to borrow fur from more hirsute species.

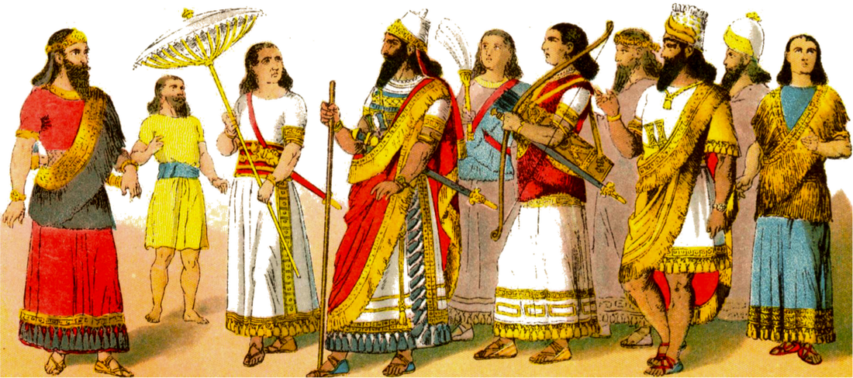

Well, up to a point, Lord Copper. The ancient civilisations that grew up in the fertile valleys of the Euphrates, the Nile and the Indus, were more tropical than a Wham! video, and clearly using their outfits to signify status, occupational, sex and gender differentiation.

Some may even have wanted to be regarded as individuals — despite we modern types imagining we invented all that — cutting a dash with a tufted Mesopotamian fringe here, or supple Egyptian weave there.

I raise the question because the issue of why we dress is feeling modish again, and not merely because the great grounding brought about by Covid has made comfort king.

The costumes of both genders had been heading in this direction already — what with normcore, athleezure, and the lemming-like “casualisation”. But, I’m talking about something else here, a resistance to the at-one-time uncontroversial notion of what is “flattering”, a term now considered oppressive by the young.

To quote the Guardian‘s Jess Cartner-Morley, never backward about coming forward in identifying a zeitgeist moment: “For Generation Z — roughly speaking, those born between 1995 and 2010 — ‘flattering’ is becoming a new F-word.

“To compliment a woman on her ‘flattering’ dress is passive-aggressive body-policing, sneaked into our consciousness in a Trojan horse of sisterly helpfulness. It is a euphemism for fat-shaming, a sniper attack slyly targeting our hidden vulnerabilities. ‘Flattering’, in other words, is cancelled.”