Seventy-five years ago, the war in the Pacific had ended with the surrender of Japanese imperial forces after the atomic bombing attacks at Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The war may have technically ended, but there was still plenty of danger for the surviving POWs in various camps around the Japanese home islands. George MacDonnell was a Canadian soldier who had been captured in the fall of Hong Kong early in the Japanese swathe of conquest that engulfed so many areas. He had been held as a slave labourer at a prison camp in the mountains of northern Honshu in Iwate Prefecture. In Quillette, he tells how his captivity came to an end:

It was noon on August 15th, 1945. The Japanese Emperor had just announced to his people that his country had surrendered unconditionally to the Allied Powers.

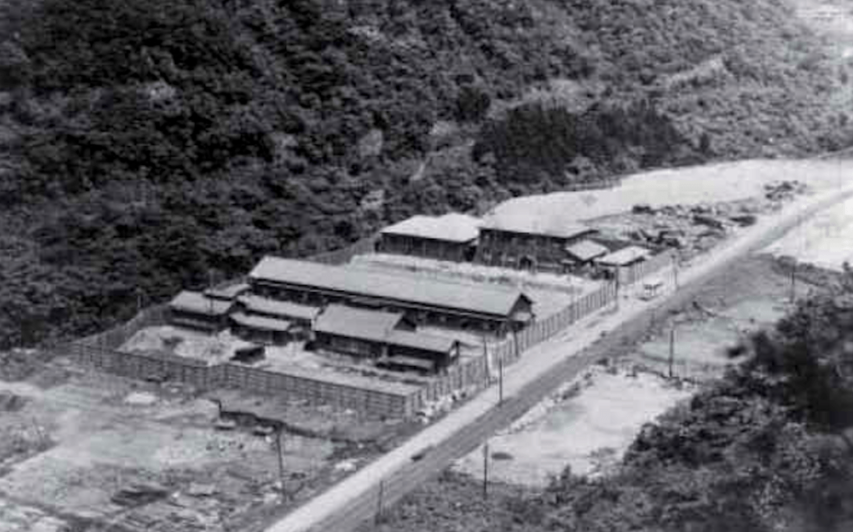

To those of us being held at Ohashi Prison Camp in the mountains of northern Japan, where we’d been prisoners of war performing forced labour at a local iron mine, this meant freedom. But freedom didn’t necessarily equate to safety. The camp’s 395 POWs, about half of them Canadians, were still under the effective control of Japanese troops. And so we began negotiating with them about what would happen next.

Complicating the negotiations was the Japanese military code of Bushido, which required an officer to die fighting or commit suicide (seppuku) rather than accept defeat. We also knew that the camp commander — First Lieutenant Yoshida Zenkichi — had written orders to kill his prisoners “by any means at his disposal” if their rescue seemed imminent. We also knew that we could all easily be deposited in a local mine shaft and then buried under thousands of tons of rock for all eternity without a trace.

We had no way of notifying Allied military commanders (who still hadn’t landed in Japan) as to the location of the camp (about a hundred miles north of Sendai, in a mountainous area near Honshu’s eastern coast), whose existence was then unknown. Because of the devastating American bombing, Japan’s cities had been reduced to rubble, its institutions were in chaos, and millions of Japanese were themselves close to starvation, much like us. The camp itself had food supplies, such as they were, for just three days.

Lieut. Zenkichi seemed angry, and felt humiliated by the surrender. Yet he appeared willing to negotiate our status. And after some stressful hours, we reached an agreement: The Japanese guards would be dismissed from the camp, while a detachment of Kenpeitai (the much feared Military Police) would provide security for Zenkichi, who would confine himself to his office.

To our delight, the local Japanese farmers were friendly, and agreed to give us food in exchange for some of the items we’d managed to loot from the camp’s remaining inventory — though, unfortunately, not enough to feed the camp. Meanwhile, through a secret radio we’d been operating, we learned that the Americans were going to conduct an aerial grid search of Japan’s islands for prison camps. We followed the broadcasted instructions and immediately painted “P.O.W.” in eight-foot-high white letters on the roof of the biggest hut.

Two days later, with all of our food gone, we heard a murmur from the direction of the ocean. The sound turned into the throb of a single-engine airplane flying at about 3,000 feet altitude. Then, suddenly he was above us — a little blue fighter with the white stars of the US Navy painted on its wings and fuselage. But the engine noise began to fade as he went right past us. Please, God, I thought — let him see our camp.