In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes looks at some of the “bottom-up” educational initiatives that helped create and shape the industrial revolution:

I stumbled across a speech the other day, delivered by Dr Olinthus Gregory — the mathematics teacher at the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich — to the Deptford Mechanics’ Institution. The mechanics’ institutions, or institutes, were created by working men pooling their savings to pay for lectures, libraries, educational equipment, news-rooms, and book clubs. They spearheaded Britain’s bottom-up approach to adult education, with the classes held in the evenings after work. But they’re a story for another time.

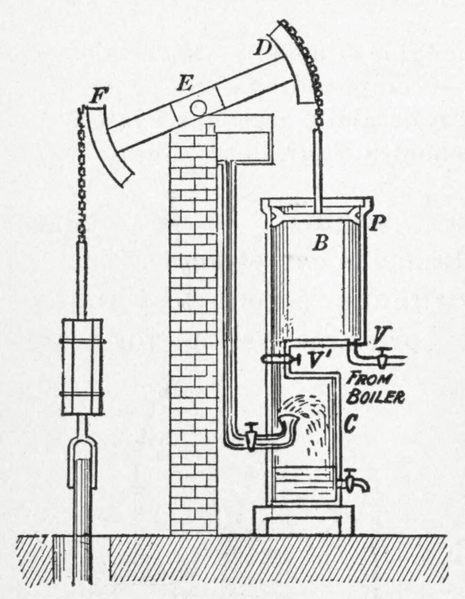

Diagram of a Watt steam engine from Practical physics for secondary schools (1913).

Wikimedia Commons.What caught my eye was Gregory’s speech. Delivered in 1826, Britain’s industrial prowess was already obvious to many. The Industrial Revolution was already in full swing. Gregory paints the picture perfectly:

Agriculture, manufactures, commerce, navigation, the arts, and sciences, useful and ornamental, in a copious and inexhaustible variety, enhance the conveniences and embellishments of this otherwise happy spot. Cities thronged with inhabitants, warehouses filled with stores, markets and fairs with busy rustics; fields, villages, roads, seaports, all contributing to the riches and glory of our land.

But there was more to be done. After all, everything can always be improved (an attitude that I call the improving mentality):

Recollect farther, that every natural and every artificial advantage is susceptible of gradual progression, and trace the yearly elevation to higher perfection. New societies for improvement … new machines to advance our arts and facilitate labour; waste lands enclosed, roads improved, bridges erected, canals cut, tunnels excavated, marshes drained and cultivated, docks formed, ports enlarged: these and a thousand kindred operations which present themselves spontaneously to the mind’s eye, prove that we have not yet attained our zenith, and open an exquisite prospect of future stability and greatness.

Progress had been made, but there was always room for more.

As for the causes, Gregory had some interesting observations. Important, he said, was coal: “more valuable to us than the gold mines ever were to Spain, since without these the various metals could not be worked, and half our manufactories would be at a stand.”

But coal alone was not enough. There would be less output, of course, but he did not say that progress would have been stifled altogether (which is also more or less my own position). Also important was that inventors could persuade the government of the benefits of innovation, which is something I mentioned in my last email. As Gregory put it, Britain had “a government of whom the arts and sciences never crave audience in vain.”

And most important of all was Britain’s community of inventors and scientists, from the Boultons and Watts and Smeatons and Arkwrights and Bramahs, to the Donkins, Hornblowers, Trevithicks, Maudslays and Stephensons (only a few of whom are at all heard of today) …