Jordan Chandler Hirsch reviews a new book on what is now a somewhat forgotten international crisis that shook the Atlantic alliance, Philip Zelikow’s Suez Deconstructed:

Zelikow encourages readers to assess Suez by examining three kinds of judgments made by the statesmen during the crisis: value judgments (“What do we care about?”), reality judgments (“What is really going on?”), and action judgments (“What can we do about it?”). Asking these questions, Zelikow argues, is the best means of evaluating the protagonists. Through this structure, Suez Deconstructed hopes to provide “a personal sense, even a checklist, of matters to consider” when confronting questions of statecraft.

The book begins this task by describing the world of 1956. The Cold War’s impermeable borders had not yet solidified, and the superpowers sought the favor of the so-called Third World. Among non-aligned nations, Cold War ideology mattered less than anti-colonialism. In the Middle East, its champion was Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser, who wielded influence by exploiting several festering regional disputes. He rhetorically — and, the French suspected, materially — supported the Algerian revolt against French rule. He competed with Iraq, Egypt’s pro-British and anti-communist rival. He threatened to destroy the State of Israel. And through Egypt ran the Suez Canal, which Europe depended on for oil.

Egypt’s conflict with Israel precipitated the Suez crisis. In September 1955, Nasser struck a stunning and mammoth arms deal with the Soviet Union. The infusion of weaponry threatened Israel’s strategic superiority, undermined Iraq, and vaulted the Soviet Union into the Middle East. From that point forward, Zelikow argues, the question for all the countries in the crisis (aside from Egypt, of course) became “What to do next about Nasser?”

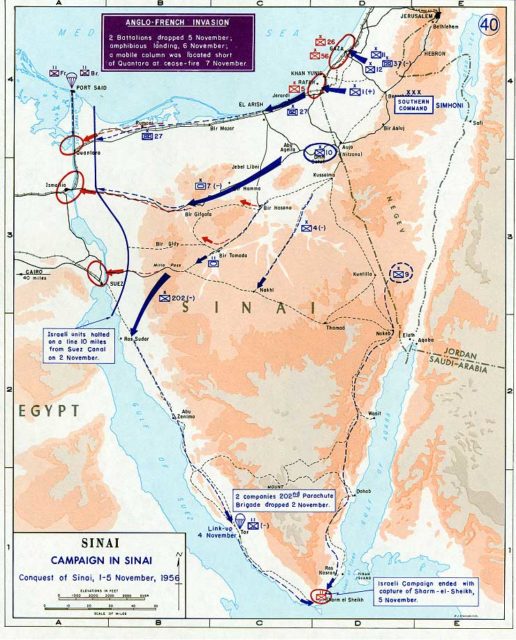

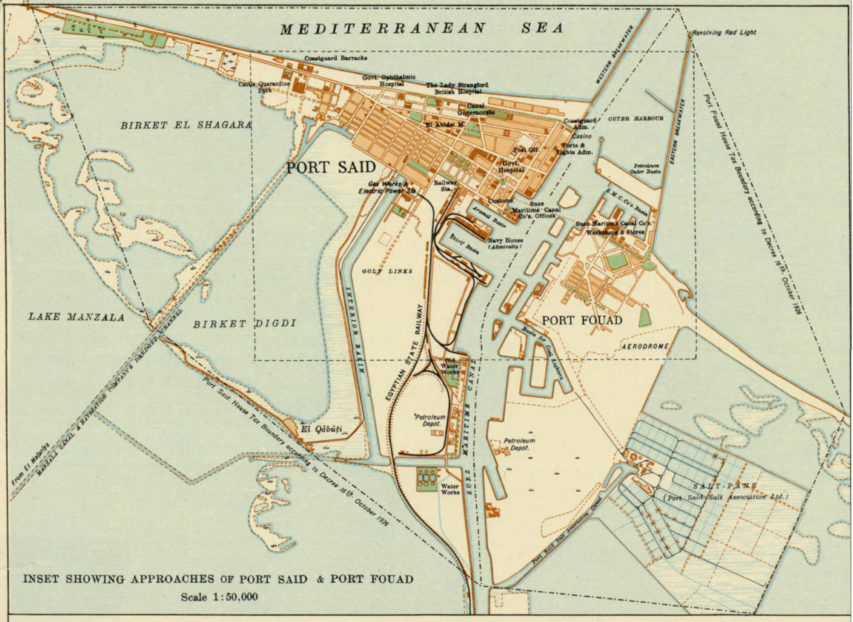

Israel responded with dread, while, Britain, France, and the United States alternated between confrontation and conciliation. Eventually, the United States abandoned Nasser, but he doubled down by nationalizing the Suez Canal. This was too much for France. Hoping to unseat Nasser to halt Egyptian aid to Algeria, it concocted a plan with Israel and, eventually, Britain for Israel to invade Egypt and for British and French troops to seize the Canal Zone on the pretense of separating Israeli and Egyptian forces. The attack began just before the upcoming U.S. presidential election and alongside a revolution in Hungary that triggered a Soviet invasion. The book highlights the Eisenhower administration’s anger at the tripartite plot. Despite having turned on Nasser, Eisenhower seethed at not having been told about the assault, bitterly opposed it, and threatened to ruin the British and French economies by withholding oil shipments.

Throughout, Suez Deconstructed disorients. As the story crisscrosses from terror raids into Israel to covert summits in French villas, from Turtle Bay to the Suez Canal, names and places, thoughts and actions blur. Venerable policymakers scramble to comprehend the latest maneuvers as they struggle with the weight of history: Was Suez another Munich? Could Britain and France still project power abroad? Would a young Israel survive?

If you’re not familiar with the Suez Crisis and want more than just the Wikipedia article for background, here’s the coverage of the military side of things from the British perspective (Operation Musketeer) from Naval History Homepage.