Extra Credits

Published on 12 Jan 2019Sun Yat-sen spends the next ten years following his London adventures trying to organize the rebellion in Tokyo — and ends up not recruiting just Chinese reformers, but radical fighters from Japan and the Philippines too.

Join us on Patreon! http://bit.ly/EHPatreon

January 14, 2019

Sun Yat-sen – An Army in Exile – Extra History – #3

Lysander Spooner and the US postal system

Naomi Mathew recounts the battle between anarchist Lysander Spooner and the United States Post Office:

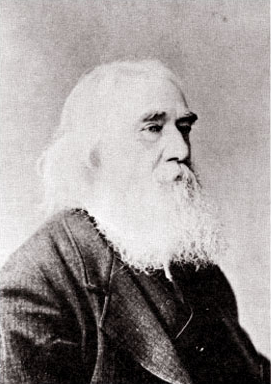

This is a story about a philosopher, entrepreneur, lawyer, economist, abolitionist, anarchist — the list goes on. As his obituary summarizes, “To destroy tyranny, root and branch, was the great object of his life.” Although he is rarely included in mainstream history, Lysander Spooner was an anarchist who didn’t merely preach about his ideas: He lived them. No example illustrates this better than Spooner’s legal battle against the US postal monopoly.

Born in 1808 in Athol, Massachusetts, Lysander Spooner was raised on his parent’s farm and later moved to Worcester to practice law. Eventually, he found himself in New York City, where business was booming — but not for the Post Office.

The Postal System of the 1840s

In Spooner’s day, government subsidized the cost of building infrastructure used for mail routes. Postage rates paid for these subsidies, which in turn made the rates expensive. For example, in 1840 it cost 18.75 cents, over a quarter of a day’s wages, to send a letter from Baltimore to New York.

Corruption was another issue facing the post office. Positions appeared to change after each election cycle, indicating political cronyism. Congress was also under pressure from the coach contractor lobby, and favorable postage routes were often given to contractors with political connections. Thanks to a legal monopoly it had enjoyed since the Confederation, the Post Office remained the sole legal mail business despite its skyrocketing costs and corruption.

In his book Uncle Sam, The Monopoly Man, William Wooldridge describes how high postal costs led some to defy postal laws: Traveling individuals doubled as temporary, private postmen. By the 1840s, these illicit services were chipping into government revenues. Eventually, a court ruled it legal for individuals (but not companies) to carry mail. As a result, underground mail enterprises sprung up. Agents covertly used the existing rails, coaches, and steamboats to transport letters. It is estimated that in 1845, a third of all letters were transported by private mail firms.

Rerailing a Steam Locomotive

Fort Wayne Railroad Historical Society

Published on 26 Oct 2016Watch as our volunteer crew made up of veteran railroaders, experienced mechanics and new recruits wrangle our 200-ton steam locomotive back on the rail. This was no easy way to spend a Saturday. For those curious, the boiler was filled with compressed air to help move the locomotive and the 765 was temporarily renumbered “767” to honor the engine’s unique place in history: http://fortwaynerailroad.org/2016/08/…

QotD: Eisenhower’s Middle East policy about-face

Unlike some American presidents, however, Eisenhower learned from his mistakes. In 1958, five years after being sworn into office, he reversed course. Rather than suck up to Egypt, Ike deployed American Marines to Lebanon to shore up President Camille Chamoun, who was under siege by Nasser’s local allies.

“In Lebanon,” Eisenhower wrote in his memoirs, “the question was whether it would be better to incur the deep resentment of nearly all of the Arab world (and some of the rest of the Free World) and in doing so risk general war with the Soviet Union or to do something worse — which was to do nothing.” That is almost verbatim what the British said to justify their own war against Nasser when Eisenhower slapped them with crippling sanctions.

Reality forced the United States into a total about-face. Ike’s entire Middle Eastern worldview collapsed. Even before sending the Marines to Lebanon he announced that America was taking Britain’s place as the pre-eminent power in the Middle East. He had to start over even if he didn’t want to. “Nasser,” Doran writes, “the giant who rose from the Suez Crisis, crushed Eisenhower’s doctrine like a cigarette under his shoe.”

What happened between the Suez Crisis and Eisenhower’s intervention in Lebanon? A couple of things.

Ike’s hope to bring Syria into the American orbit alongside Turkey and Pakistan collapsed in spectacular fashion. So many Syrians swooned over Nasser after Egypt’s victory in the Suez Canal that Syria, astonishingly, allowed itself to be annexed by Cairo. Egypt and Syria became one country—the United Arab Republic—with Nasser as the dictator of both.

Washington’s attempt to groom Saudi Arabia as a regional counterbalance to Egypt also hit the skids when Nasser accused the Saudis of trying to assassinate him and foment a military coup in Damascus. The Saudis responded by shoving King Saud aside and replacing him with his Nasserist younger brother, Crown Prince Faisal.

The final blow came with the brutal overthrow of the pro-Western Hashemite monarchy in Iraq and the mutilation of the royal family’s corpses in public, thus toppling the last pillar of America’s anti-Soviet alliance in the Middle East. Eisenhower had no choice but to stop being clever and return to the first rule of foreign policy: reward your friends and punish your enemies.

Michael J. Totten, “We Are Still Living With Eisenhower’s Biggest Mistake”, The Tower Magazine, 2017-02.