In Pragati, Alex Tabarrok reviews Shashi Tharoor’s 2016 book history of the British Raj, An Era Of Darkness:

At sophisticated dinner parties in Delhi, Calcutta, or Chennai, whenever the discussion turns to politics, one can be sure that sooner or later, and usually sooner, the British will be blamed. It’s a fine parlor game, and clever players can usually find a way to cast blame for whichever side of the debate they favor. Is India’s traditional family falling apart due to internet porn? Blame the British! Are the laws against homosexuality too strong? Blame the British! The British are an easy target because much of what they did was reprehensible. But blaming British imperialism for contemporary Indian problems is also an easy way to let India’s political class off the hook.

An excellent case against the British comes from Shashi Tharoor, bestselling author, former Under-Secretary-General at the United Nations, and current member of the Indian parliament, in his 2016 book An Era of Darkness: The British Empire in India (also published this year under the title Inglorious Empire[UK title]).

Tharoor makes three claims:

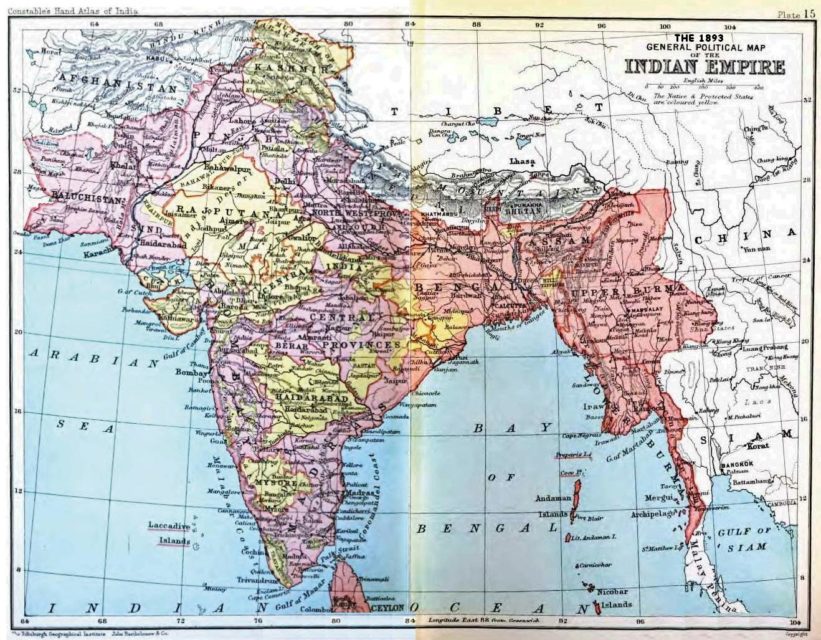

- The British empire in India, from the seizure of Bengal by the East India Company in 1757 until the end of British government rule in 1947, was cruel, rapacious, and racist.

- India would be much better off today had it not been for British rule.

- Britain’s success and the Industrial Revolution were due to British depredation of India.

The first claim is true, the second uncertain, the third false.

The first claim is the heart of Tharoor’s book: the British empire in India was cruel, rapacious and racist. All true. But who would expect otherwise? Power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely. The theft, the famines, the massacres, the formal and casual racism, the utter hypocrisy of suppressing independence while using hundreds of thousands of Indian soldiers to fight for democracy and freedom in two World Wars — on all this Tharoor stands on solid ground. The ground is solid in part because it has been well-trod. Tharoor brings the case against the East India Company and Britain, initiated by Edmund Burke (1774-1785) and continued by the likes of Indian nationalist Dadabhai Naoroji [PDF] (1901) and American historian Will Durant (1930), to its conclusion and climax with the Indian independence movement. In this, Tharoor is entirely successful and his work deserves to be widely read.

In his eagerness to blame Britain, however, Tharoor reaches for every possible argument in ways that are sometimes misleading and sometimes absurd.